|

Monday, February 9, 2009

Progress Notes

The political season that just ended this last year had its share of disputes, disagreements, and differences of opinions with the occasional loss of temper or intemperate remarks but we survived it even though a different political party now is in control in Washington. Things weren’t quite so calm back in the mid 1800’s especially in Miller County, and today, I doubt that the average person knows just how much strife and discord existed then during and especially after the Civil War. Here in Miller County, because of the fairly even mix of Southern and Northern supporters, violence was common even among civilians and between families as well. According to Clyde Lee Jenkins, author of History of Miller County V I and II (photo 01), the period from 1861 to 1874 “was one of the most lamentable and vicious intervals in the history of the County.”

01 Clyde Lee Jenkins

Clyde documented numerous oral histories told him by descendents of Civil War veterans who described terrible acts of violence and vengeance between neighbors and even within families. Clyde was able to gather these stories beginning in the 1940’s after he returned to Miller County upon being discharged from the Navy at the end of WWII. At that time many people were still alive who were witnesses especially of the post war era up through the 1870’s when tensions and anger were still very prevalent in the county. For example, my mother who now is 87 years old, can remember talking with her great uncle Absalom Bear, who fought with the North in the war (photos 02 and 03).

02 Absalom Bear War Photo

03 Absalom Bear many years after the War

Actually, Clyde Lee documents violent activities beginning in the county in the 1850’s and lasting well into the 1870’s.

Although Miller County now is predominately Republican, that wasn’t the case in the beginning of its history. In fact, according to Gerald Schultz (photo 04) in his History of Miller County:

04 Gerard Schultz

“From the time of its organization until the beginning of the Civil War, the county was predominantly Democratic” (p. 52).

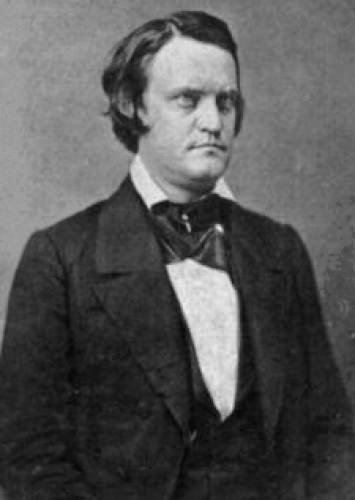

In all the presidential elections held in the county from 1840 until 1864, the county voted for the Democratic candidate. In 1860, Abraham Lincoln only received 25 votes! The Southern candidate, John Breckinridge (photo 05), who was known as the “candidate of the extreme pro slavery men of the South, polled 61 percent of the total vote of the county with 495 votes.

05 John C. Breckinridge

A third candidate, John Bell of the Union Party polled 193 votes” (Schultz p. 53) (photo 06).

06 John Bell

The change in attitude of the county about Lincoln as well as the Southern cause mainly was due to the extreme indiscriminate violence brought to the county by Southern sympathizers who were traveling with the Confederate General Price’s units (photo 07) as well as “bushwhackers” (such as William Quantrill, photo 08) who, in many cases, were no more than common criminals.

07 General Sterling Price

08 William Clarke Quantrill

Clyde Lee Jenkins’ history of this period of time in his History of Miller County documents many incidents of criminal activities perpetrated by Southern sympathizers, many of whom were from areas outside the county. However, Clyde Lee also documents that our own citizens cannot be excused; time after time residents of the county themselves were fighting among themselves over the issues of slavery as well as allegiance to either the South or the North regarding the issue of maintaining the Union.

It was into this environment that the subject of this week’s Progress Notes, Methodist Minister Thomas J. Babcoke, was assigned to this area by the Missouri Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1860 (photo 09 Note: This photo is from a website discussing Babcoke but it did not have his name placed directly under the photo. So I am making an assumption this is he. Otherwise, I can find no other photo of Babcoke.).

09 Thomas Babcoke

Even though he was a minister and not prone to violence, he found himself involved in an evolving dispute among members of the Methodist Episocopal Church in Missouri and throughout the South over the issue of slavery. He was a popular figure and even was elected to the State Legislature after the war. But before I write further about Babcoke, more background history is important to cite.

This week’s narrative will not have many photos of Miller County Civil War soldiers because it is rare to find a Civil War era photograph having been taken in Miller County. We do have on our website a group of photos taken of the six Bear brothers who fought for the North but a collection such as these is very unusual:

http://www.millercountymuseum.org/people/bio_b.html

You will need to scroll down the page to get to the section about the Civil War Bear Brothers.

Also, we have run across occasional old group photos of members of the “Grand Army of the Republic,” an organization of soldiers who fought for the North who met regularly years later after the Civil War was over. Here is a photo of the Brumley GAR group (photo 10).

10 Brumley GAR

Click photo for larger view

Here is a list of whom we have identified in this old photo:

Front Row: first man on left is James Martin Hawkins (1847-1934), 6th man is

James Lewis Pemberton (1845-1931),10th and last man is James Mastin Wornell

(1843-1932).

Back Row: 3rd man from left is Emanuel Lett or Jett (a black

man). The man in the white shirt standing in front of the flag is Henry

Clay Jackson (1839-1932).

Hawkins and Wornell are buried in Hawkins Cemetery. Pemberton is buried in

Williams Cemetery. Jackson is buried in the Eldon Cemetery. I don't have

any information on the black man. Peggy Hake says his name was Jett and

Verna Pemberton says Lett.

You can read more about Miller County GAR groups at this URL on our own website:

http://www.millercountymuseum.org/organizations/gar.html

Early on the Methodist Circuit Riders were numerous in the county at one time numbering twelve different preachers traveling different circuits in the county. According to Clyde Lee (History of Miller County, V I p.235), many abolitionists traversed the area of Miller County since it was an area where slavery persisted. The Methodist Church, becoming active in this work, was soon divided by the question into Northern and Southern factions. Eventually a vote on the division of the church in Miller County occurred at Smyrna (a church south of the river in what is known as the “Little Richwoods Area”) in 1846. As Clyde Lee writes: “In Holy Assembly the Methodists of local circuits voted unanimously for allegiance to the Methodist Episcopal Church, South.”

The following, copied from sections of Clyde Lee Jenkins’ History of Miller County V I (p. 235-263), gives an example of the violent emotions evoked in some Miller County citizens associated with the question of abolition:

In January, 1849, Bob Wilson, a fiery preacher of the Methodist Episcopal Church, arrived at the Courthouse, in Tuscumbia, to preach on the evils of slavery. His assistant, a young man in his early twenties, spread work of the meeting throughout the village.

Nearing the appointed hour, an immense crowd of angry citizens were under the hill, having gathered in the dram shops. Daniel Cummings, noticing the people’s temper, believed the abolitionist preacher would be lynched, which should happen to no Methodist!

Daniel Cummings, with Champ Smith beside him, hastening up the hill, entered the Courthouse, informing preacher Wilson if he started preaching, the people would kill him. They persuaded Wilson to leave, but his young assistant remained behind.

This young man was handsome, having a fine open forehead. His hair and complexion were fair; his air and carriage very commanding. He was possessed of great courage, yet this youth, with all his fine qualities, was the occasion of infinite hatred to many of the mob.

When the crowd arrived on the hill the youth was seized, manhandled, and tied to a post in front of the Courthouse. His shirt was torn off, and there were cries of “Burn him at the Stake!” Champ Smith, grabbing a cat-o-nine tails, a whip, viciously popped it a few times, which quieted the crowd.

In a low voice he calmly told the youth something had to be done or the crowd would take his life. Smith handed the whip to Sheriff S.C.H. Wittgen, who administered twenty lashes upon the bare back of the youth.

The mob, satisfied, dispersed.

On Saturday, February 3, 1849, the citizens of Miller County held a mass meeting at Tuscumbia. At this meeting it was decided no preacher or missionary entertaining abolitionist principles could preach or hold meetings in the Courthouse. J.W. Johnston and Robertson Roberts were appointed to wait upon the County Court, and inform the Justices of their decision.

On February 6, 1849, the County Court noted that “We the Justices, in common with our fellow citizens, have seen occasioned the disruption of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States,” that the Northern potions of this Church were pushing men into this state under the appellation of preachers or missionaries solely to disturb the present arrangement peaceably and amicably entered into, and carried out in good order.

The Justices indicated, instead of being messengers of peace and good order as they pretended, they were sowing the seeds of dissension and discord, not only in the Northern portions of the Christian family, but by disturbing the harmony and peace of society in general.

The County Court noted it would exercise full and complete control over the public property committed to its charge by law and by the suffrages of the citizens of Miller County. For the benefit of the citizens in general the use of public property by any person or persons deemed injurious to the interest of the community would be denied.

The County Court then ordered the County Clerk never to allow the use of the Courthouse to any person or persons entertaining abolitionist sentiments sent “in our midst to stir up strife in a now peaceable and orderly society, on a question so vitally affecting the interests of the whole community.”

At this time, the Methodist Church was the most influential in the county having established the very first church house in Miller County in the “Big Richwoods” south of the Osage River. This church, which was constructed of logs, was raised in 1834 and was named the Smyrna Church. Early on the Baptist and Methodists both used the church for worship. In the 1850’s ill feelings arose between the Baptist and Methodist congregations using the building, so the Baptists decided they would build a house of their own. This group left the Smyrna Church and built another one of logs on a lot where now is located the Iberia Cemetery. When the Baptists moved in, a few of their members remained at Smyrna. This group labeled the new church congregation “selfish, bigoted, and sulky.” From this the “Sulky” Church was born!

With characteristic zeal, the Methodist Episcopal Church involved its ministers and membership in the abolition movement. When a temporizing course was adopted allowing congregations, or circuits, to vote on the question, the Church divided into two factions; the Northern against slavery, the Southern for slavery. In conference at Smyrna, in 1846, the Methodists in Miller County voted unanimously for allegiance to the Methodist Episcopal Church, South.

The first church building in Tuscumbia was a Methodist Church erected by Champ Smith, in February, 1860. However, soon after that the sending of abolitionist preachers into Central Missouri by the Methodist Episcopal Church and then the great upheaval and division of the church over slavery, resulted in significant disorganization of the church in Miller County. Internecine conflict completed its destruction. The Methodist Church building at Tuscumbia, no longer having enough members to sustain a viable church organization, was rented to house a saloon during the Civil War. It was later destroyed by fire. In 1866 at Pleasant Mount, the trustees sold the Methodist church house, parsonage, and grounds to private interests. Eventually Hite’s Chapel ceased to exist, and the Smyrna congregation moved into Maries County, embracing another denomination. Thus the largest congregation in the earlier days of the county’s history, Methodism deserved a better fate!

Now I will turn to the subject of this week’s narrative, Thomas J. Babcoke. The fact is, history remembers him not for his preaching, although he was considered an excellent preacher, but for his skills at leadership in his role as a Northern sympathizer fighting for the Union cause in Miller County. Captain Babcoke has almost as many citations in books and writings about the history of the Civil War in Miller County as has other perhaps better known figures such as Emil Golden or William Carroll Brumley.

Peggy Hake (photo 11) has written a short biographical sketch of Captain Babcoke which I will copy here:

11 Peggy Hake

Thomas J. Babcoke

Civil War Hero of Miller County

By Peggy Hake

On the 31st day of January, 1866, the Missouri House of Representatives adopted a resolution to investigate charges made by The Missouri Republican newspaper against the Honorable Thomas J. Babcoke, a member of the 23rd General Assembly of Missouri. A committee was formed and an investigation went forth concerning an incident that began in Miller County and concluded in neighboring Phelps County to the southeast.

Thomas J. Babcoke Sr., an early day Methodist minister, was elected as a State Representative from Miller County in the election of 1864 during the Civil War era of Missouri’s history. Thomas, his wife Lovey, and their family, moved into Miller County and settled in Franklin township north of the Osage River. Thomas and Lovey had at least two children and perhaps three, including Thomas Jr., Edwin, and George, all born in Ohio. The Babcoke family was in Vermont as early as the census of 1790 where several families were living in Rutland and Windsor counties of central Vermont.

Being from Upper New England, the Babcokes were Union sympathizers and at the beginning of the Civil War in Missouri, Thomas Sr. was enrolled at Locust Mound (later called Spring Garden) as a Major in the Cole County Home Guards which later became company I commanded by Captain Daniel Rice of which the Miller County Cavalry were part. This Company helped to secure the north side of the Osage River for the Union. Later Thomas was promoted to a Colonel.

Throughout the Civil war years in central Missouri, Major Thomas J. Babcoke constantly was on the heels of the guerilla leader of the Confederates, General Crabtree, who rampaged, pillaged, and murdered all over Miller County and surrounding area during those days. In April, 1864, Babcoke’s command captured a number of Crabtree’s men, one whom was John P. Wilcox. The Wilcox family were early settlers of Miller County from Scott County, Virginia, who homesteaded south of the Osage River in what is known today as the Wilcox Bend of the Osage.

When it was learned that some of Crabtree’s troops were captured, an order was issued by the Military District of Central Missouri at Warrensburg that John P. Wilcox (who was being held prisoner at Jefferson City) was to be executed immediately. These orders were carried out in August, 1864 when John Wilcox was shot as a war criminal at Weirs Creek in Cole County. On August 24, upon hearing that one of his men had been executed, Crabtree and his band of marauders killed seven Miller County militia men on Curtman Island in the Osage River of northeastern Miller County. The seven men, including Samuel McClure, John Starling, Wiley Gibson, Richard Crisp, Nathaniel Hicks, Yancy Roar, and Pharoah B. Long, were lined up and shot executed style.

The foregoing information sets the stage for what happened in 1865 which caused charges to be leveled against the Honorable Thomas J. Babcoke, formerly Colonel Babcoke of Civil War fame.

According to testimony, a Miller County man named William Conner was taken from his field where he was plowing, and was killed by two bushwhackers. They were identified as George Connelly and Anthony Wright. Anthony was the son of Judge Lewis Wright of Phelps County. Conner’s murder was a horrendous act committed by these two blood thirsty bushwhackers. They took William Conner into the woods, shot him down, and repeatedly fired into his body. He had begged for mercy in the name of his wife, Dorcas, and their young children. The Conners lived north of the Osage in Franklin township on a small farm they had worked since their marriage in September 1850. After they killed Mr. Conner, the two men took his horse, saddle, pistols and some of his clothing. Before they left him, his murderers set fire to his body and when found later, part of his body had been destroyed by fire. William L. Conner died at the hands of his enemies on 26 May 1865.

When it was learned that William Conner had been so viciously murdered, Colonel Thomas Babcoke and some of his neighbors, joined forces and tracked the two men to the house of a widow named Mariah Wilcox (widow of William L. Wilcox). Her daughter, Lucinda Wilcox, was responsible for directing Connelly and Wright to the Conner farm. It was stated she did this because William Conner was one of the men responsible for the killing of her brother, John P. Wilcox, the man who was executed as a member of Crabtree’s guerilla army. Before and after the killing of Conner, the two men hid out in a cave near the Wilcox farm and supposedly Lucinda carried food to them.

By the time Babcoke got there, the men had disappeared. It was rumored they were heading southeast to Phelps County where Wright lived with his parents, Judge and Mrs. Lewis F. Wright. Colonel Babcoke and his band went to Phelps County in their search and were led to the home of Judge Wright by a widow lady named Nancy Bottom. There they found the black stallion of William Conner which had been stolen by Connelly and Wright.

Hearing that the area was overrun with bushwhackers, Babcoke and his few men returned to Miller County for reinforcements. They did not return immediately because Babcoke went to Jefferson City and received orders from the Governor to activate one hundred men in Miller County as a militia. During this time, Babcoke must have had some clout in the Capitol City because he was a member of the 23rd General Assembly which was in existence during 1865.

When Babcoke and his command went back to Phelps County, they rode to the home of Judge Wright once again looking for his son, Anthony. While at the Wright home, the horse of William Conner was still there along with the saddle and the coat of the murdered man. Each of the Wrights claimed the coat belonged to them. First Mrs. Wright said it was the Judge’s…the Judge said, “No, it belonged to one of his sons”….the son said it belonged to another brother and so on…Finally, Mrs. Wright admitted the coat had been brought home by her son Anthony. Judge Wright and four of his sons were arrested on the spot including David, Lews, Jr., Benjamin, and Tarleton. Anthony had disappeared. Colonel Babcoke ordered one of his men, Captain H.G. Bollinger, to escort the Wrights to Rolla so their testimonies could be officially taken in the presence of a Justice of the Peace. His orders were…”Take charge of them and treat them well, but don’t let them get away. Turn them over and the evidence with them.” Mrs. Wright insisted on going with them also and she rode a few hundred yards behind the party.

About six miles from their home, the Wrights tried to escape from their captors. Captain Bollinger ordered them to halt. They did not and he ordered his men to fire. Judge Wright’s body had 2 bullet wounds; David Wright received 6 wounds; Lewis Wright, Jr. had 5 gunshot wounds; Benjamin Wright received 8 shots upon his body; and Tarleton Wright died of 4 gunshot wounds.

Bollinger returned to his commanding officer, Colonel Thomas J. Babcoke, and reported the facts. They started back to Miller County but were overtaken by orders from General Beredge, who had command of the District. When Babcoke appeared before General Beredge, he presented him with the evidence which proved he had the authority “to march in that country.” The General immediately released Babcoke and his militia to return to Miller County. In the meantime it was learned that the civil authorities had taken steps to cause his arrest, so Babcoke went to these authorities and demanded an investigation of his act. He and his men marched to the house of the officer of the law, ordered his men to disarm, and turn their arms over to the law. It wasn’t too long afterward that a Grand Jury brought a “not guilty” bill forward and they were all released to return to Miller County.

Five months later in January, 1866, the newspaper, The Missouri Republican, of Jefferson City, leveled new charges against Thomas Babcoke, a State Representative in the Missouri General Assembly. Once again a committee reviewed the evidence of the mass killings of the Wright family but their findings resulted in a dismissal also.

(Note: Babcoke was thought to be a Radical Republican, which was a minority group opposing the participation of any Southern sympathizer in the political process as well as enjoying other various civil rights. So possibly those opposed to the Radicals were trying to find a way to remove him from office.)

Babcoke never served in Miller County’s political field after the one term. Sometime between 1870 and 1880, the Babcoke family left Miller County. The only Babcoke family left in the census of 1880 was Joseph N. Babcoke, his wife Martha, and their three daughters. I believe Joseph was a grandson of Colonel Thomas J. Babcoke.

Thanks Peggy.

An interesting confirmation of the story of the Conner killing is contained in a short paragraph which is part of a narrative C.B. Wright (photo 12) wrote about his maternal grandfather, Richard Boyce, concerning his immigration to Miller County.

12 C.B. and Tennyson Wright

Richard’s daughter and C.B.’s mother, Mary Emma, had told C.B. the following story which C.B. included in his narrative:

“In 1866 the heat of the Civil War was not fully cooled and shortly after the family moved to their new home, Captain Babcoke rode to the front door and inquired of Mrs. Boyce, "Are you folks loyal?" Mrs. Boyce had to talk to the Captain for the reason that Mr. Boyce was not at home and they learned later that Captain Babcoke, though a Unionist, was somewhat of a renegade character. Sometime the same year an old gentleman by the name of Conner called on Mr. Boyce and told him, "I have a son hanging from a limb down on Indian Creek. Like to have you go with me to take care of the body.”

You can read the entire story about Richard Boyce, as written by C.B. at this URL on our website:

http://www.millercountymuseum.org/people/bio_b.html

You will need to scroll almost all the way down the page to get to the story written by C.B. about Richard Boyce and his family. I think these cross confirmations of stories such as the Conner killing are important for the purpose of reinforcing in our minds first their authenticity, and second, to render in some way to the reader the depth of the hatred in our county among its citizens over the issues which brought about the Civil War.

I happened to come across an old book published in 1868 written by a Methodist Episcopalian minister, Reverend Charles Elliott, D. D., LL. D. which gives Babcoke’s story in his own words. Most of the narrative was written by Babcoke with a few paragraphs at the end added by Reverend Elliott. This is a long narrative and perhaps only the most “historophilic” reader will navigate through it; but it is an actual first person account of some interesting Civil War history in our county which I wanted to preserve here on our website:

SOUTH-WESTERN METHODISM.

A HISTORY OF THE M. E. CHURCH IN THE SOUTH-WEST, FROM 1844 TO 1864.

COMPRISING THE MARTYRDOM OF BEWLEY AND OTHERS; PERSECUTIONS OF THE M. E. CHURCH, AND ITS REORGANIZATION, ETC.

BY REV. CHARLES ELLIOTT, D. D., LL. D.,

AUTHOR OF "DELINEATIONS OF ROMANISM," "SINFULNESS OF AMERICAN SLAVERY,"

“THE BIBLE AND SLAVERY," "THE GREAT SECESSION," ETC.

EDITED AND REVISED BY

REV. LEROY M. VERNON, A. M.

Of the Missouri and Arkansas Conference.

CINCINNATI:

PUBLISHED BY POE & HITCHCOCK,

FOR THE EDITOR.

R. P. THOMPSON, PRINTER.

1868.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1868,

BY LEROY M. VERNON, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Eastern District of Missouri.

ACADEMY OF PACIFIC COAST HISTORY PEERAGE.

CHAPTER XX. P. 309

THE HEROIC MAJOR.

THE following narrative, from the pen of Rev. Thomas J. Babcoke, formerly of the Missouri Conference, Methodist Episcopal Church, will be read with interest by every Christian and patriot. It is difficult to decide which excels, his Christian character, his pure patriotism, or his masterly generalship. He is worthy to command a regiment, and yet he was deprived of his Major's commission by Governor Gamble just because he was a radical, or uncompromising Union man, and a member and minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church; for, according to the ideas of Governor Gamble and his conservative, or secession, allies, any one of these characteristics was sufficient ground for degrading him from office. It was a dark day for Missouri when President Lincoln, honest man that he was, was misled by the so-called conservatives of Missouri. Although Mr. Babcoke lost his

commission because he voted for Mr. Lincoln, was a "Northern Methodist," etc., he was, nevertheless, first to take arms again to repel the invasion of the traitor Price. But let Mr. Babcoke speak for himself:

BROTHER ELLIOTT,

I take this opportunity to pen you a few items of my history in Missouri. In December, 1859, I arrived in Shelby County, and tarried a short time in Shelbyville, the county seat. I there became acquainted with the Methodist Episcopal Church South. They politely offered me that station for the rest of the year. I declined, and started, with my effects, for the Osage country, where I landed in January, 1860. I purchased a small farm in Miller County for our home. The people seemed kind and accommodating till I inquired for the Methodist Episcopal Church; then the inquiry arose, 'Does he belong to the South or North Church?' I informed them I belonged to neither, but was a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Learning brother McKnight had an appointment three miles distant, I attended and gave in my letter. The news flew like wild-fire. Then commenced the cry, 'He is an old abolitionist, and has come here to steal our Negroes.'

I strove to counteract the report, but all in vain; the Southern preachers strove to give it publicity from the desk. They declared the Methodist Episcopal Church was an abolition Church employed by the North to steal and run off Negroes. Then they began their persecution, threatening to tar and feather and drive me from the country, and even threatening my life. They frequently met me at my appointments, and ordered me to leave and not return. I still attended to my duties and filled my appointments, notwithstanding their threats. At length I resolved to meet their charges publicly. I appointed a day for that purpose. I tried to show our position. For a few days things were quiet. This was against the 'Church South.' They lost ground unless they kept the people inflamed with a spirit of persecution. For the purpose of kindling the public mind against us, Rev. John D. Read, a Southern Methodist of Miller county, announced a lecture at one of my preaching places, and requested me to meet him. I went. He brought a Rev. Mr. Marcus with him. They refused to let me reply, and their general treatment of me was such as one might have expected at a country groggery. Read tried, by insults and low-bred slang, to wound me and excite the people against me. They lectured six hours to prove we were all abolitionists. They quoted largely from the Northern Independent, and told the people that paper was published by the Methodist Episcopal Church. This they stated some twenty times. They also read several resolutions passed by the abolitionists, and declared they were passed by the Methodist Episcopal Church. Their sole purpose was to fire the people against us, and force us to leave the country. While making his false charges against us, Mr. Read, pausing, asked, 'What ought to be done with such people?' An old Mr. Wilks spoke out, 'They ought to be served as 'Ray was,' alluding to a man hung by a mob.

Such was my treatment at the commencement of my labors in Missouri. The preachers above alluded to were both from the North. They were acquainted with the Methodist Episcopal Church, therefore, and knew their statements were false. I was compelled to hear their falsehoods, without the privilege of correcting a single error. Gross insults were heaped upon me during the lecture. At the close I rose and told the people that fully two-thirds of the charges made against us were base falsehoods, and, denied the privilege of replying there, I would meet them in four weeks, and try to correct public sentiment in reference to

the Church.

I met the people on the day appointed, and endeavored to show them our position on the slavery question. Such experiences and events filled up the first two years of my life in Missouri. Every falsehood and insult that could be invented was heaped upon the Church. Several times they met to mob me, but the providence of God preserved me. In Johnson County a mob, headed by a Baptist doctor, was coming in sight of me, when some of my friends informed and advised me to leave. This was so contrary to my disposition that I resolved to meet them and defend myself, at all risks, but a lawyer of the place prevailed on the mob to disperse. It would require a volume to detail all the insults of which I was the subject on account of my connection with the Church they loathed.

When the rebellion broke out they redoubled their persecution. I was abused in every assembly. It was publicly declared I should die. A Southern Methodist preacher said to one of my neighbors, 'He can never escape; they are determined to kill him.' It was a trying moment. I looked in all directions for a friend, and, for some time, thought myself alone. I visited a family by the name of Duncan, who had been friends to me indeed. I shall never forget the day they said to me, 'We are still your friends.' Some of them wept, and said, 'I can see no chance for you; they are determined to kill you.' For a moment all looked dark, but, quick as thought, this came to my mind, ' I will shield thy head in the hour of battle.'

I returned home, not knowing what course to pursue. My family became alarmed, and urged me to leave the State. This was impossible. I was without money. They had a consultation, and resolved to take my life. A tree was selected for my gallows. About this time I was employed at to drill a company, which was said to be for mutual protection. I hoped by so doing to receive protection; but in this I was disappointed. A friend informed me they had resolved to reject me; for said they, 'He will be killed, and we want true Southern men to command us.'

This took me by surprise. But as another expedient we resolved to make an effort to raise a Union company. At this juncture, Captain Johnson, a rebel chief, sent twenty men to take me. But when they came I was not at home.

Drill-day came for the first company. I informed them I had learned of all their plans, and would save them any further trouble. I spoke in favor of the Union, and warned them to be careful what they did. When I closed, a Mr. Bliss called for Union volunteers. I stood still. To my astonishment forty enrolled for the Government. I was called upon to command them. We prepared as fast as

possible for defense.

Our second meeting was in Tuscumbia, Miller County. That day we captured two pieces of artillery, concealed in a rebel's hay-mow. The rebels then banded together to attack us. I met them in person, gave them my reasons for enlisting, and told them of their abusive conduct. Some of them swore I should not leave alive.

I warned them of the consequences. Returning home the next day, I was informed that they had resolved anew to take my life, and were then on the way to execute their threat. I then determined to engage in the war in earnest.

I told my family not to look for me till they saw me coming. I started to Jefferson City to make some arrangements for our defense. I stopped at a blacksmith's shop, near Hickory Hill, to get a horseshoe set. The shop bench was covered with gun-locks and other fragments of fire-arms. The smith inquired, 'Where are you from?'

My answer was evasive: 'I am from the South-West.'

'Do you know of any companies being raised out there for the Union?'

'I believe I do.’

'What are the names of the commanders?'

I paused as if to study. He then asked,

'Is there one called Babcoke?’

I paused a moment, and answered, 'yes, he is called a hard case.'

'Yes,' he said, 'but we will stop his career soon.'

I encouraged him to do so. He then said, 'We are making up a company to take him as he passes down to Jefferson.'

I told him to be very careful whom he told this to, for we did not know whom we might be talking to.

'Ah!' said he, ' I know whom to trust.'

He gave me the names of the leaders of the gang, which were Peter Taylor, of Morgan County; James M'Kinsey, of Cole, and Dr. Waters, of Miller. I learned their whole plan, and then left him ignorant of whom he was talking to. After making the necessary arrangement, I started with my command for Jefferson City. We got through without harm, though we were waylaid by Taylor and his gang. Failing in this attempt, two hundred of them leagued

together to take us on our return. The commander at Jefferson City, learning this, ordered Colonel Mulligan to accompany us with a part of the Irish brigade. While passing Hickory Hill we were fired upon by a small gang of skulking rebels, but without effect. We then marched to Mt. Pleasant, Miller co., and found it evacuated. The next day we found all kinds of goods in almost all kinds of places. We sent teams and gathered them in. There were dry goods, groceries, hardware, boots and shoes, caps and hats, provisions and medicines, all boxed up and hid out in hollows and thickets. Only two Union men were living in the place. It was a rallying point for rebels. A Southern Methodist Church was there, and their meetings

were frequently improved by prayers and lectures in favor of the South. Wm. P. Dickson, of this place, was a leading rebel and a Southern Methodist. It was this Dickson who said, 'These Northern Methodists are all Negro thieves, and ought to be driven from the State.'

He is the man, also, who solemnly affirmed before God, there were no contraband goods on his premises, and in less than two hours

we dug up one hundred and fifty pounds of powder buried in his stable. When found, he acknowledged he put it there. He it was, too, who took the oath of allegiance, and solemnly swore to reveal every thing coming to his knowledge of a treasonable character. And still he kept this powder concealed with which to kill Union men.

This raid into Miller County was all placed to my charge. If I was before the object of their hate, I was now much more so. They now sought my life with redoubled energy. My family was insulted by both males and females. They would pass my house, using the most abusive language possible. The cries of 'old abolitionist,' 'negro equality,' and the like, fell upon the ears of my wife daily. They destroyed my farming utensils and all other articles of value they could get hold of. A short time after this a choice pack of seven chivalrous men came to my house in my absence and ordered my wife to leave, under penalty of death. I give the names for the benefit of their posterity; namely, Berry Taylor, Preston Taylor Jr., 'Brit' Taylor, Elijah Spence, one Hilman, and one Hase, all members of a professed Christian Church ! After this gentlemanly act they concealed themselves in the brush, and Calvin Tindal, another Baptist, cooked provision, and with his wife carried it to them.

The abuse daily heaped upon my family occasioned me to move them to Jefferson City for protection. I remained there during the Winter. The dangers and uncertainties of war-times had prevented me from making any thing during the year for support. Living in the city soon reduced my little stock to a very small pittance. My family again beset me to leave the State.

But where should we go, and what should we have when we got there were questions of no small import. In fact, there was no alternative but to stay and fight it out. I resolved at once to move back to my farm.

Contrary to the advice of my friends and entreaties of my family I started, arriving in March, 1862, with my goods on my own premises. Immediately the word came that the rebels had determined to kill me or force me to leave. I was informed of their council at Judge Wilks's, and of their decision to attack my house at a given time.

I immediately prepared my house for defense. I procured fire-arms enough to have given them twelve shots. With these I resolved to stand my ground. They learned of my preparation, and so did not come. But the most horrid threats and bitter oaths human depravity could invent were daily fulminated against me. Still God was near to deliver.

Notwithstanding all their menaces we planted a small crop of corn, and, for a time, tilled it; but before we 'laid it by' the guerrillas were prowling through the whole State.

In the Spring of 1862, the Conference appointed me to the Otterville circuit. I made several attempts to reach the circuit, but was as often intercepted by bands of guerrillas. I seemed more than any one else in all the country the object of their hate. They sought my life with zeal worthy of a better cause. Failing in all efforts to reach my field of labor I at last abandoned the idea of trying to do the work of a circuit preacher. I devoted myself, as far as possible, therefore, to my farm, working and watching by day, and sleeping at night, with two double-barreled shot-guns, two pistols, and an ax so near my bed that I could lay my hands on them any moment.

Thus I lived till the time above mentioned, when the guerrillas commenced their work of plunder and death. Then I entered the service again in the militia. Scouting and fighting occupied us till cold weather came. And though our fighting was not as severe

as that experienced in many places, we saw enough to learn the horrors of war. Cold weather setting in, the guerrillas disbanded or went South, and we were called to Jefferson City, where we remained till March 1, 1863. Then we were furloughed home to report for duty at a moment's call.

During all this time we had received nothing for our services. I served five months in- the Home-Guards, and seven in the militia, living upon my own limited means. Many of our families were in a most destitute condition. Undergoing every privation ourselves, the horrifying intelligence almost daily reached us of peaceable Union citizens being shot down in their doors or in their fields. Others were attacked and robbed of coats, hats, shoes, jackets, and some were stripped of their pants and socks. Houses were often robbed of the last vestige of wearing apparel, and even bed clothes were taken, and bedticks emptied to make rebel shirts. Women and children were driven from their houses and the houses burned before their eyes. I have seen family after family fleeing for safety, their feet bound up with rags to keep them from freezing. I have listened to accounts of suffering, and the weeping of mothers and children till my heart grew sick. In the midst of all this desolation, speech after speech was made in the North reprobating the Government, and eulogizing the South. These reached us, and aggravated our sufferings. Such men will have their reward. They will be hated on earth, excluded from heaven, and loathed even in hell.

Notwithstanding the fiery trials of these times, we had some manifestations of the goodness of God in the outpouring of his Spirit. We had some excellent meetings. In the Fall of 1860 we held a camp meeting in Proctor, in Morgan county, near the residence of Rev. B. F. Wilson. It will long be remembered. About one hundred conversions were witnessed. Many promising young men were of the number, some of whom are gone to their reward.

When the war broke out these young men flew to their country's aid. While I write, my soul rejoices at the remembrance of the happy prayer meetings of those young converts, in their tents or in some secret spot outside the army encampment. But where are they all now? Some have fallen in battle, others by slow but fatal disease. One of the number, a brother Wilson, was accidentally shot, and we found him only in time to see him die. The rest are still filling their places in the Union army. May God preserve them and our country! I am still in the service of the State, and probably, will be till the war closes.

"I have not been able to note one circumstance in a hundred, but I have given the outline of the whole"

ROCKY MOUNT, MILLER COUNTY, Mo., April 18, 1863.

Thomas J. Babcoke

The following appeared in the Missouri Democrat of October 21, 1864, toward the close of Price's last raid into Missouri. The writer, from Jefferson City, makes the following statement as prefatory to the article:

"The hero, Captain Babcoke, was a Major in the Home-Guards, at the commencement of the war; and afterward a Major in the E. M. M., from which position he was removed by Governor Gamble, through the influence of Colonel Flesh, commanding the regiment, for being a Radical.

(Note: The Radicals were a group of Republicans who attempted to exclude from the party anyone who had sympathized with the Southern side during the Civil War. This animus by the Radicals toward suspected Southern sympathizers arose naturally since early on many Miller Countians were for the Southern cause although some changed their minds later due to their abhorrence of the mindless killings and destruction brought to the county by Price’s Army and the many Southern supporting bushwhackers which invaded the county. Also, some Southern supporters who later changed their minds and fought for the North still risked the deprivation of certain rights such as voting as well as pensions unless they signed an affidavit swearing they were supporters of the Union cause. According to Clyde Lee Jenkins in his History of Miller County VII p. 9, 10) a Constitutional Amendment was passed in 1870 abolishing any “oath of loyalty” which was being required of the Democrats to vote. Allowing the Democrats to vote would have challenged the post war rule of Republicans in Miller County. Clyde further writes: “In the election of 1872, ex confederates, and Southern sympathizers entered the campaign with vim and vigor. Without any doubt this was the bitterest political contest ever waged in Miller County. There was much fighting among the inhabitants, with broken noses and much spilling of blood.”)

He is (Babcoke), besides being a worthy and most reliable citizen, a man of great decision of character, courage, and self-reliance, and he possesses in a peculiar degree the quality recommended by

Danton, “Audace, audace, toujours audace!" Thus in English, “Bold, bold, ALWAYS BOLD!”

"On the 7th instant, April, 1864, Captain T. J. Babcoke, being in command of a militia company, organized under Order 107, was returning from Rolla to Jefferson City, with thirty men, mounted, having been sent to the former place with dispatches from General Brown to General M'Neil. About twelve miles from Jefferson City he came upon a rebel picket-guard of thirteen men, including a Captain and Lieutenant, at a farm-house, part of the party being inside the house. Thinking a bold course the better one under the circumstances, he rode up to the sentinel in the road with the greatest coolness, and when the sentinel halted him, he said, in a commanding tone, ' Halt yourself!' and assumed such an authoritative air, that the rebels supposed him to be one of the officers of their own army, making the grand rounds. It must be remembered that Price's rebels are sometimes clothed by whole companies in Federal uniform. The rebels, thus thrown off their guard, permitted Captain Babcoke and his men to ride into the yard. As soon as the house was surrounded, Captain Babcoke told the whole party of rebels to surrender, in such tones as told them they were sold. He had men that he could rely upon, and he ordered them to shoot down any rebel that attempted to move or use his gun. The rebels outside of the house dropped their guns, and those inside, seeing the house surrounded, surrendered at discretion. The horses of the rebels were hitched at some distance in the woods; these the Captain sent for, and mounting his prisoners, two officers and eleven men started for Jefferson City.

“This capture was within one mile of Price's main column, and Captain Babcoke soon found himself like the man who won the elephant in a raffle. He had 'got a good thing;' the point was to 'keep it.' But the mind that conceived the capture of the rebel outpost was fertile in expedients. He placed his prisoners in the front, and started to go around the rebel army, which lay between him and Jefferson City. He crossed the Osage several times, and made a number of narrow escapes from running directly into the rebel lines. He was tangled in the bends of the Osage like Mr. Raymond in the 'elbows of the Mincio,' at the battle of Solferino, but he knew the country, and succeeded in effectually dodging the whole rebel army.”

“On the next day after the capture of his prisoners, while riding down a hill, he saw a rebel company descending a hill opposite, and coming toward him. He conceived that his safety lay in boldness, and, with his thirty men and thirteen prisoners, he charged on the rebel company with a yell, and drove them back. Each prisoner had two or more men especially to look after him, as well as after the enemy in front, and the captured rebs, instead of being an encumbrance, were an advantage, as they helped to swell the numbers of Captain Babcoke's force, and make it appear more formidable. No sooner had he got the rebs in front of him on the skedaddle than he made a sudden detour by a by-path, and got into the brush. It was afterward ascertained that the skedaddlers reported to Price that the Federals were advancing in force in their rear, and he had his army drawn up in line of battle to meet them.”

The rebels were hunting for Captain Babcoke for six days, knowing he could not have reached the Federal forces at Jefferson City. The brave men of his company had a tedious time camping out nights, and, between guarding their prisoners and keeping a watch-out for the enemy, they had little time for sleep. Six days and six nights were thus passed, when Captain Babcoke and his faithful band safely arrived in Jefferson City, and delivered to General Brown their thirteen prisoners, who are now safely confined here."

Quite a few references and anecdotes are made about Thomas J. Babcoke in Clyde Lee Jenkins’ writings about the Civil War both in Volumes I and II. He certainly was one of the major figures fighting for the North in the Miller County area during the Civil War. Reference to him also is made in Gerard Schultze’s History of Miller County as well.

Another anecdote about Captain Babcoke is told by Clyde Lee Jenkins in his History of Miller County V I :

“Captain Babcoke Confronts The Rebel Army" p.445

The Provisional Company E.M.M., at Pleasant Mount, Captain Thomas J. Babcoke, commanding, with First Lieutenant Thomas G. McClure, and 85 infantrymen, 60 mounted, fell back on Jefferson City, September 30.

The Provisional Company E.M.M., at Tuscumbia, Captain Sayles Brown, commanding, with 50 men, approximately one half of the company, escorted the records of Miller County, carried by County Clerk I.M. Goodrich, from the Courthouse to the capitol building in Jefferson City for safekeeping; Captain Sayles Brown, and most of his men returning to the County Seat with Captain Benjamin Jeffries.

In connection with orders issued by Federal Brigadier General E.B. Brown, commanding at Jefferson City, Captain Thomas J. Babcoke, with 30 men, 15 belonging to Captain Brown’s Company, and 3 to Captain Long’s, because of their knowledge of the country, were detailed to carry dispatches to Rolla. Armed with new Smith & Wesson’s rifles they crossed the Osage River at Tuscumbia, early in the morning of October 3.

At this time guerillas and bushwhackers were in the area by the hundreds, acting as scouts and the advance guard for the main columns of the Confederate Army, under the command of General Sterling Price, on the Osage River.

Captain Babcoke and his men, pursued by mounted men, were fired upon a number of times, but having scouted the country so frequently, every path and by road was known to them, and constantly, by changing the direction of their travel, successfully avoided capture, reaching Rolla, October 4.

On the evening of October 8, near sundown, Captain Babcoke, and his men were opposite Tuscumbia, on the south bank of the river. With low water before them, they forded the Osage, riding into the village. In less than an hour, having paused for refreshments and provision, they rode north to the Big Saline Creek, passing up the Lick branch, taking the left-hand to the ridge east of present-day Etterville. Here Captain Babcoke, dismounting his men, encamped for the night.

At the breaking of dawn, the militia men were aroused by peculiar noises; sounds of a fiddle playing, a dog barking, a norse neighing, some men yelling, and guns firing not too far distant. Captain Babcoke, ordering his men to mount up, moved along until the dirge exploded upon their ears in all its fullness. By the present day home of Colonel Max Atkinson, near the breaking of the ridge, east of Etterville, they came upon a Confederate hanging party.

It was a strange sight!

A human body hung from a rope thrown over a tree limb about ten feet up. Around this body circled a number of men, dancing or keeping cadence with the rhythm of a tune played by a long haired fiddler, standing and stomping, on a large flat stump, close by, some four feet above the ground. A little dog, jumping inside the circle of dancing men, kept growling and barking, keeping crude time, almost, with the fiddler’s rhythm. To the right, and slightly behind the fiddler, stood a number of worn and shaggy nags, looking upon the scene or nibbling grass.

Lemmuel Miller observed the scene before his eyes for only a few moments. Raising his gun, he took careful aim, firing it. From the large tree stump the fiddler fell, dead! Gunfire rang out, and three more men fell, as the Confederates, scattering from the hanging tree, hastened to their horses. Upon touching the saddle, they plunged their mounts down the ridge, while Babcoke’s men poured a galling fire upon them. A horse falling under one of the men, somersaulted, staying down, killed the rider, hitting the ground a runnin’, picked up by another horseman passing at great speed.

Captain Babcoke, and his men, removing a Swanson lad of Pleasant Mount from the hanging tree, having suffered death, rode north, down Brush Creek, into Cole County. Here the Captain commenced noticing for some reason unknown to him, the main roads were filled with soldiers of the Confederacy.

Upon hearing the firing of the cannon, the reason dawned upon him in complete fullness. They were in the path of the main Confederate Army under command of General Sterling Price. It was certain they would be fired upon and killed, or captured, at any moment.

The Captain, approaching the large rebel columns, by quick maneuvering, passed around them, until, near Stringtown, Babcoke eased his men into a dense grove of wild cherry trees, stopping. For some time they listened to the many strange sounds in the north. Men were talking, laughing, and yelling; hundreds of horses were blowing, neighing, and plodding; moving vehicles were clunging and clanking. Also, sporadic gunfire could be heard. Actually, they were within one half mile of over seven thousand Confederates.

Captain Babcoke, informing his men of the dangerous predicament they were in, indicated escape might be effected by returning toward Pleasant Mount, and the men agreeing; they commenced moving out, cautiously, southwest.

In heading up a little hollow they came upon 14 Confederates roasting three squirrels over a small stick fire. The militiamen rode upon them, almost unnoticed by the hungry Confederates who, without any doubt, believed them of their own army.

Captain Babcoke said, “Men, you are my prisoners!”

One of the Confederates, grabbing a roasting squirrel, broke for the woods, running rapidly. As guns raised, Babcoke yelled, “Hold your fire!” Gunfire might attract attention.

Babcoke ordered the arms of all Confederates tied behind their bodies. He ordered their weapons taken from them. Then having the Confederates mounted upon their own horses, and moving by way of thick woods and by paths to avoid capture, entered Miller County moving rapidly south. By nightfall the Confederates were in a barn, on the present day farm of Sam Graham, near the Glenwood Baptist Church house.

A stake and rider fence, of great height, around this barn, made it easier for the prisoners to be watched and guarded by Boyd S. and Lemmuel Miller, of Babcoke’s company.

That evening, Boyd S. Miller’s mother, Hannah Garsten Miller, and her two daughters, Anna and Polly, visited Boyd and Lemmuel, and talked with the Confederates. Hannah lived on the present day farm of John Curty. Her daughter, Anna, later married J.J. (Jeff) Haynes, and Polly married a Mr. Wyrick.

The following day the prisoners were taken by Babcoke’s men to Vienna, in Maries County, reaching there by dodging the many Confederate companies and marauding bands of guerillas then in the area. Afterward, within a few days, when it was safer to travel back north, Babcoke and his Miller County boys, reaching Jefferson City in safety, delivered the 13 confederate prisoners to proper authority.

William Sims Gartin, then just a chunk of a boy, found a belt and pistol on the stake and rider fence by the barn aforementioned, left there by one of the militia men. He put on the belt, taking the pistol. Since the weapon was in excellent condition, Mr. Gartin used this pistol for many years for shooting squirrels, rabbits and other small game.

So ends my narrative about Captain Thomas J. Babcoke, Civil War hero of Miller County. However, an abbreviated epilogue can be added:

Peggy Hake wrote above in her narrative about Captain Babcoke that “between 1870 and 1880 the Babcoke family left Miller County.” The reason given is not known for sure; however, I read the following in Gerard Schultz’s History of Miller County p. 65:

“The house of Thomas J. Babcoke was burned by ‘reconstructed rebels’ on the night of December 31, 1867.”

Gerard added nothing else before or after that sentence in reference as to where Babcoke went after the fire!

Quite possibly, Captain Babcoke may have continued to experience difficulties with Southern sympathizers well after the war ended. We’ll never know for sure because references to him in the time period after the Civil War cannot be found in any of our Miller County literature nor could I find further information about him from other sources elsewhere. Certainly, it has been documented that quarrelling and fighting persisted up through the 1870’s in the County’s post Civil War history. Perhaps Babcoke moved with his family back East from where he came, but I couldn’t document that.

Last week I received the following letter from Sue Helton Jarrett (photo 12a) who with her husband, Tennyson, now lives near San Diego California.

12a Sue Helton Jarrett

You may remember that the Jarretts’ were the ones who donated to the museum the old original barber chair which last was used by Tennyson when he barbered in Tuscumbia. Sue has always been an educator and I thought many would be interested in what she has accomplished in her chosen field after leaving Miller County:

Dear Joe,

Again, we want to thank you for the interesting history of Tuscumbia.

I'm so glad you have help in preserving history of the rural schools - it has been such a part of both of our lives - Tennyson attended school at Elliott, Keyes and Hickory Point and I started to school at Bear and then finished at Pisgah - then, at 16, I taught my first year at Pisgah (I don't tell my student teachers that I supervise at National University and Chapman University that I didn't have student teaching - I just taught like Miss Jessie Nixdorf and my other teachers, using the Missouri Course of Study). I taught one year at Pisgah (1947/48, two years at Spring Garden, two years at Wilson, Korea happened and my school board at Wilson allowed me to teach on Saturdays to fulfill the maximum days of the school year so that I could come to San Diego with Tennyson after he finished boot camp in April 1952. That Fall, after seeing him off to Japan on board USS Andromeda, I drove back to Missouri in our 1948 Kaiser by myself and Carroll McCubbin called and asked me to teach a 7th grade at Dixon because the teacher had been in a car wreck). I was the last teacher at Spring Garden and Wilson, due to consolidation. In the meantime, I completed my Bachelor of Science in Education and taught two years in a private school, then we returned to Tuscumbia in May 1966 and taught there two years and Tennyson barbered. We returned to San Diego in Fall 1968, and I had a contract to teach fourth grade in the National School District, then later became Principal for eleven years, completing twenty-eight years in Elementary Schools. I retired in June 1986 and then in February 1988, I was asked by National University to supervise student teachers, helping them get their teaching credentials. Also, Chapman University asked me to supervise student teachers for them - so I'm Adjunct Faculty at both Universities and it fulfills my desire to "keep going" in an environment that I love.

Keep on making our Monday mornings interesting!

We'll see you in July when we're at Helton Family Reunion.

I had the opportunity last week to present a discussion of Miller County History to the St. Elizabeth 7th and 8th grade classes as part of a program entitled “Junior High Speaker Day” under the direction of teachers Janice Wieberg and Nicole McDonnell. This program was described to me by Nicole as follows:

“Janice and I arranged this program last year. She gets two science speakers and I get two social studies speakers. My speakers were you and members of Blaine Luetkemeyer's campaign staff. The Luetkemeyer campaign staff discussed the importance of voting, and the "selling" of a candidate. Janice's were Mary Reidmeyer from Missouri S&T and speakers from the Runge Center in Jeff City. Mary Reidmeyer discussed the properties of glass and did several experiments, such as making a rudimentary fiber optic cable and blowing up glass. The Runge center had the students dissect owl pellets to Janice Wieberg determine what "creatures" that owl had eaten. We divide the 7th and 8th graders into four groups. They rotate among the four speakers in 30 minute segments. We do not have a name for this event. We just call it the Junior High speaker day.”

I was very impressed by the student’s interest in my talk and their thoughtful questions. I think it is a wonderful idea to expose our young folks to the history of our county and their ancestors’ accomplishments. I know that the teachers these days have very little time to add special opportunities such as this program due to the requirements they face with their other teaching responsibilities, so I want to give credit to the teaching staff at St. Elizabeth for including Miller County history in their program last week. I had four different groups scheduled for my talk and here is a photo I took of one of them (photo 13):

13 St. Elizabeth Eighth Graders

That's all for this week.

|