|

Monday, November 23, 2009

Progress Notes

A couple of weeks ago the nation celebrated Veterans Day, an event which seems each year to be increasingly respected and honored by our citizenry. To some extent, it seems that veterans of previous service to our country are more revered as we become more aware through the visual images of television newscasts of present conflicts just how awful and terrible are the experiences faced by our soldiers in battle. One area of the country which makes a special effort to honor veterans is Branson, Missouri, one of the nation’s most popular areas to visit due to the variety and number of live musical and comedy shows presented. I and Judy visited Branson the week of Labor Day. The town was full of veterans of all ages who came to attend special events, meetings and rendezvous in an environment which makes a special effort to recognize them. Any one who has attended one of the many popular stage shows there knows that invariably throughout the entire year all veterans are recognized before the shows begin.

Our weekend began with a concert given at the Branson Landing by the United States Air Force Band from Scott Air force Base of Illinois (photo 01).

01 United States Air Force Band The concert was followed by a huge hour long parade which marched down the half mile street adjacent to the Branson Landing. Many of the parade marching groups were made up of various military associated organizations (photo 02).

02 Veterans Day Parade Fox News was present represented by Colonel Oliver North, who was given a very enthusiastic reception by all the veterans (photo 03).

03 Colonel Oliver North Here at home the veterans also were enthusiastically recognized. The many events honoring our veterans were covered very well by the Vernon Publishing Company newspapers. I was proud to see that my cousin, Jim Pryor, who served in the Navy during the Vietnam War, was video taped by one of the Autogram’s reporters offering a short comment about Veteran’s Day.

Here is the video clip (photo 04):

Click on the small triangle at the bottom left of the photo to start playing the video.

At our museum, we have dedicated an entire section of the first floor for the display of artifacts, photos, and memorabilia of our own Miller County veterans of previous wars. Also, at various times, I have presented stories on this website of the military experiences of some of our Miller County heroes of the past. One story of heroism by an American soldier has always stood out in my memory. I hadn’t put it on the website at first because the soldier was not from Miller County. However, there is a Miller County connection. You see, the soldier, George McHugh, an air force pilot during WWII, was the uncle of my son in law Daniel McHugh, who was born and raised in Chicago. The story was detailed in this narrative by George’s sister, Josephine (McHugh) Stefanatos:

Villagers of Pontpoint Honor 1st Lt. George McHugh (photo 05)

05 Lt. George McHugh Condensed From Articles by Josephine (McHugh) Stefanatos in Contrails

June 16, 1944, 379th Bomb Group mission No. 144.

The Group’s target was the airdrome at Laon/Couvron, France. In the lead position of the low squadron was B-17G #42-313648, Ensign Mary. Its pilot was 1st Lt. George McHugh.

Other members of his crew were 2nd Lt. Edward I. Peterson-co-pilot; 2nd Lt. Robert D. Reese-navigator; 2nd Lt. Charles R. Atkinson-bombardier; T/Sgt. Russell J. Groat-radio operator/gunner; S/Sgt. J. Kelly Shaw-ball turret gunner; S/Sgt. George Thompson-waist gunner; and S/Sgt. Bruce Little-tail gunner.

1st Lt. McHugh’s crew was flying its 30th combat mission. At 25,000 feet the squadron encountered intense and accurate flak shortly before reaching the target. Although a direct hit by a flak shell set McHugh’s Flying Fortress ablaze, he was able to stay with the formation until its bombs were dropped on the assigned target. With his bomber’s engines on fire, McHugh put Ensign Mary into a deep dive in an apparent attempt to extinguish the flames. He ordered his crew to bail out, but stayed at the controls of his Fortress. He managed to maneuver Ensign Mary away from the village of Pontpoint. His heroic action prevented his bomber from crashing into homes and buildings in the village. McHugh was killed when his aircraft crashed in a field at the village’s perimeter. The villagers managed to remove his body from the plane when the Germans left the aircraft unguarded after several days He was given a burial of the highest honor from France.

The fate of the other crew members is as follows:

Lester A. Tullier: Killed in Action

Robert D. Reese: Prisoner of War

Charles R. Atkinson: Prisoner of War

Russell J. Groat: Prisoner of War

George Thompson: Prisoner of War

Bruce Little: Prisoner of War

Edward I. Peterson: Evaded, Returned to England

J. Kelly Shaw: Evaded, Returned to England

In 1950 George’s body was brought to the United States and was buried in Holy Sepulcher Cemetery in Chicago, Illinois.

Residents of Pontpoint built a monument honoring Lt. McHugh in the center of the village square. McHugh’s name is on one face of it, and on the other side are names of French soldiers from the area who died in the war. One of the propellers from Ensign Mary is imbedded in a concrete base in front of the monument. The farmer on whose land Ensign Mary crashed established a shrine where he found that propeller.

In 1972 a new street was constructed in Pontpoint. It was named Rue Mac Hugh in honor of 1st Lt. George McHugh. In 1994, on the 50th anniversary of D-Day, the village of Pontpoint celebrated that historic event by honoring the memory of Lt. McHugh. Invited to the event were Josephine (McHugh) Stefanatos, sister of Lt. McHugh, her husband Gregory, other members of the family, friends and survivors of Lt. McHugh’s crew.

On October 27, 1997, a Silver Star medal and a Certificate for Gallantry in Action were presented posthumously to Lt. George McHugh, 379th Bombardment Group, 8th Air Force. He is remembered for his courageous action that saved many lives on June 16, 1944.

In 1994, on the fiftieth year anniversary of D-Day, as recorded in the above narrative, Dan and his family travelled with other members of the McHugh family to Pontpont France for the memorial celebration honoring Dan’s uncle, 1st Lieutenant George McHugh. Dan was 28 years old at the time. Of all the many memorial and celebration events given for the McHugh family, Dan remembers most the conversation he and his father, Bill, had with the local priest, who was the original priest of the church and school at the time of the plane crash fifty years before. Here is Dan’s summary of what the priest told them:

“The B-17 had no rudder control. Lt. McHugh only could navigate up or down but couldn’t turn the plane. Unfortunately, the plane was heading directly toward the village, so Lt. McHugh decided he and the copilot would stay with the plane to try to land it in a field just beyond the village church. The rest of the crew was commanded to parachute out of the plane. Then flames began to envelop the cabin where Lt. McHugh and his copilot were located. Lt. McHugh commanded his copilot to abandon the plane when the flames reached the cockpit. The priest told the family the plane was coming directly toward the school, and that he and the children were at great danger. As the plane approached it was so close he could see Lt. McHugh in the cockpit and that their eyes made contact. The priest said their nonverbal communication in that instant was such that he knew Lt. McHugh was going to keep the plane in the air to avoid crashing into the school or the school yard, even though it meant he would not have time to escape. The plane, completely enveloped in flames, crashed a short distance away. Lt. McHugh was trapped inside and burned to death.

The Nazis nearby came almost immediately looking for survivors. Most of the crew escaped. However, one, who was hidden in a barn by a farmer, was betrayed by the farmer’s wife because she was afraid of retribution from the Nazis if he were to be found. The Nazis arrived and shot him.

The copilot, who had parachuted out of the plane at the last moment, suffered a broken leg on making contact with the ground. However, he was able to crawl to a well and dropped some thirty or so feet into it to hide. The Nazis checked the well two or three times during the next two and one half days while he was in the water. Each time the Nazis peered over the edge, the copilot submerged himself and evaded detection. When the local farmer finally thought it was safe, he helped the copilot to extricate himself after which the French Resistance Movement helped him escape the Nazis.

The members of the local Resistance retrieved Lt. McHugh’s body, placed it in a casket, and draped it with a French flag to camouflage it as if it were a local resident’s casket. The Nazis tried to force the local residents to divulge where Lt. McHugh’s body was located, even torturing some of them. But the townspeople were extremely and emotionally grateful to Lt. McHugh for the sacrifice of his life he had made to save their children from injury from the crashing, burning plane and never divulged to the Nazis the location of his body. Because the Nazis had made it illegal to display a French flag the town decided two weeks later to bury Lt. McHugh in the local cemetery.

Afterward, the town placed a portrait of Lt. McHugh in the school/church entryway and required all the school’s students thereafter to be made aware of the story of the American pilot who had sacrificed his life to save the village’s children and church.

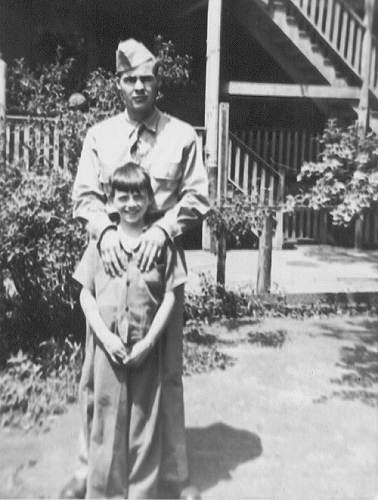

Dan and his father Bill took several photos while they were in Pontpont. First, here is a photo of Lt. George McHugh with his young brother Bill McHugh, Dan’s father, before Lt. McHugh left for Europe (photo 06).

06 Lt. George McHugh and his brother Bill McHugh Next is a photo of the memorial monument in Pontpont, France which was dedicated to Lt. McHugh (photo 07).

07 Memorial Monument in Garden The next photo is of Dan’s father, Bill, in front of the Pontpont memorial standing behind the plane propeller which had been retrieved from the crash site by the villagers (photo 08).

08 Bill McHugh, Brother of George McHugh And here is a photo of Dan at the same location the next day after decorative flags had been placed in anticipation of the memorial celebration (photo 09).

09 Dan McHugh at Memorial Both of the propeller’s blades had been bent (photo 10).

10 Propeller Blades Here is a close-up of the monument inscription in English on one side of the monument (photo 11), and another close-up of the opposite side in French (photo 12).

11 English Inscription

12 French Inscription The last photo is of the memorial monument the farmer placed in his field at the site of the plane crash (photo 13).

13 Monument in French Farmer's Field Many acts of heroism by American soldiers throughout our history may never have been recorded or celebrated. But it is especially wonderful to know about this small village in France where the townspeople were so moved by the heroism of an American pilot they decided to create their own local monument dedicated to remembering the act of courage and heroism he demonstrated which saved the lives of their children, even though it cost him his own life.

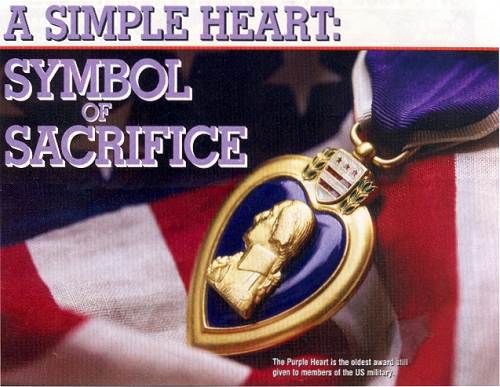

Continuing with the theme of Veterans, Acts of Heroism and Courage, I thought I would present the history of the award given recognizing those who had been wounded in action, the Purple Heart. The following article was sent me by my cousin, Max Pryor, brother to Jim Pryor mentioned above. Max also served in Vietnam in a unit which may have been involved in more fire fights than any other during that war. Max received three Purple Hearts as well as a Bronze Star during his service in Vietnam. Here is a photo of Max at an award ceremony (photo 14):

14 Soldiers receiving Vietnam Cross of Gallantry, Max Pryor second from left A Simple Heart: Symbol of Sacrifice

The Elks Magazine

Linda McMaken

November 2009

It is a simple heart of purple, attached to a purple ribbon. The oldest medal still in use that is awarded to “the common soldier.” It is available to all who serve. It is the Purple Heart…one of the most recognized and respected medals awarded to members of the US armed forces (photo 15).

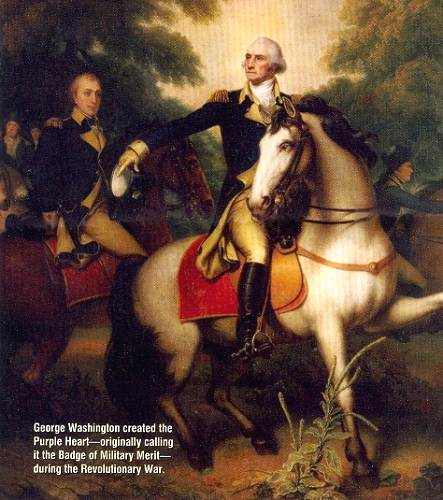

15 Purple Heart The Purple Heart is emblazoned with the profile of George Washington and is topped with the Washington family crest flanked by oak leaves. The back of the medal bears the inscription “For Military Merit.” The medal was created by General George Washington and was the result of a dispute between Washington and the Continental Congress in 1782 (photo 16).

16 George Washington Whenever Washington, always the consummate soldier, saw a soldier display bravery in action above and beyond the call of duty, he rewarded the soldier by granting him a commission or a promotion, either of which required an increase in pay. In 1782, the Continental Congress decided that it could no longer fund General Washington’s commissions. Washington then devised another way of showing his admiration, respect, and gratitude to his troops.

On August 7, 1782, Washington issued General Orders, which stated: “The General, ever desirous to cherish virtuous ambition in his soldiers as well as foster and encourage every species of military merit, directs that whenever any singularly meritorious action is performed, the author of it shall be permitted to wear on his facings, over his left breast, the figure of a heart in purple cloth. Not only instances of unusual gallantry but also of extraordinary fidelity and essential service in any way shall meet with due reward. The name and regiment of the persons so certified are to be enrolled in a book of Merit which shall be kept in the orderly room.”

Washington’s declaration, buried within the War Department Records for almost 150 years, was discovered in the early 1930’s, along with records of three of the first recipients of his purple Badge of Military Merit: Elijah Churchill, William Brown, and Daniel Bissell.

Elijah Churchill was a carpenter by trade. He joined the Eighth Connecticut Regiment on July 7, 1775. In May 1777, he reenlisted in the Second Continental Light Dragoons and stayed in the army until the end of the Revolutionary War, finishing his career as a sergeant. General Washington presented him with the Badge of Military Merit to recognize his gallantry at Fort St. George, Brookhaven, New York.

William Brown served with the Fifth Connecticut Regiment from May 1775 until January 1783. Brown received many field promotions, and army records note his Badge of Military Merit without stating the reason for the award.

Daniel Bissell was a spy and apparently a very good one. Entering the Continental Army in July 1775, he spent most of his service as a corporal in the Second Connecticut regiment. Pretending to be an American deserter, Bissell joined the British Army for thirteen months, serving under Benedict Arnold as a British regular. This position gave him access to information that he quickly and clandestinely relayed to General Washington.

The names of other recipients of the original Badge of Military Merit are unknown, and the Book of Merit mentioned in Washington’s General Orders of 1782 has never been found. After the end of the Revolutionary War, the medal was not presented again for over a hundred years.

Historians have speculated that later generals were reluctant to present a medal that was linked so closely to the legacy of one of the Unite States’ founding fathers. But in the early twentieth century, efforts began to revive General Washington’s medal for the common soldier.

In 1927, the Army Chief of Staff General Charles P. Summerall proposed that a bill be sent to Congress that would reinstate the Badge of Military Merit, as it was a particularly fitting honor for those who had served during World War I. The bill was withdrawn from congressional consideration, however, for reasons that are unknown today. The office of the adjutant general kept files of all materials relating to the bill in case the bill was revived.

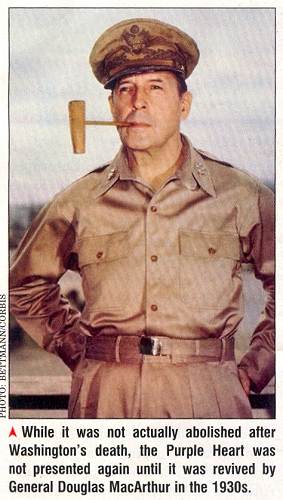

Summerall’s successor, General Douglas MacArthur (photo 17), found those files and began working confidentially on a new design for the medal.

17 General Douglas MacArthur Elizabeth Will, an army heraldic specialist, was given the task of designing the revived medal, which was to be known as the Purple Heart. Using general specifications from Washington’s original Badge of Military Merit, Will created a purple design emblazoned with Washington’s profile.

The Purple Heart was reinstituted by an executive order from President Herbert Hoover on February 22, 1932…which was the bicentennial of George Washington’s birth. The executive order stated: “By order of the President of the United States, the Purple Heart established by General George Washington at Newburgh, August 7, 1782, during the War of the Revolution is hereby revived out of respect to his memory and military achievements.”

The criteria of eligibility for the Purple Heart were announced in a circular from the War Department on the same day. Soldiers who had been awarded the Meritorious Service Citation Certificate, the Army Wound Ribbon, or who were authorized to wear Wound Chevrons subsequent to April 5, 1917…the day before the United Sates entered World War I…were eligible to apply for a Purple Heart. The first Purple Heart was presented to General MacArthur, for his service during World War I.

The medal was given to all army personnel who were “wounded in action against an enemy of the United States, or as a result of an act of such enemy, provided such would necessitate treatment by a medical officer.” In December 1942, eligibility for the Purple Heart was extended beyond the army to all branches of the armed forces. Since the end of World War II, further acts of Congress and presidential executive orders have changed the criteria for presenting the Purple Heart to include posthumous awards, awards to those injured in terrorist attacks, and awards to those wounded while serving in a peace keeping force.

The Purple Heart is different from other decorations such as the Bronze Star or the Silver Star in that an individual is not recommended for the medal: the individual is entitled to receive a Purple Heart upon meeting specific criteria…the main condition being an injury caused by enemy action. The Purple Heart is presented for the first wound received in a specific incident only: for subsequent wounds in that incident, an oak leaf cluster is added to the medal.

According to the Department of Defense, approximately 1.4 million Purple Hearts have been presented since 1932. The difficulty in determining the exact number stems in part from the practice, common from World War II to the Vietnam War, of presenting the Purple Heart in the field. Field commanders would frequently present the medal to a wounded soldier on the spot, or in a hospital, with no official record of the presentation being made. Modern day presentations of the Purple Heart are recorded on paper and electronically, and a citation and a certificate are presented to the recipient.

The Purple Heart is small, measuring barely two inches across. It has no measurable weight, and it isn’t the brightest of military medals…in fact, its deep purple color is less noticeable than other, more brightly colored service medals and ribbons. Some people do not consider the Purple Heart as meritorious as other medals, like the Silver Star or the Medal of Valor. Yet the Purple Heart is the one military award that is available to all military personnel in recognition of their willingness to sacrifice for their country. Its modest size and even its color embody the original ideals of it illustrious creator. When George Washington directed that his medal for “meritorious action” be cut from purple cloth, he was deeply aware of the royal associations of that color and of the implicit meaning of this medal: if ordinary men and women act like kings, they should be royally rewarded.

I was drafted also during the Vietnam era in 1969. At the time, I was finishing my general rotating internship. Because I already had declared my intention to specialize in the area of physical medicine and rehabilitation, the Army decided to have me continue my training since that was a specialty needed regarding the rehabilitation of those soldiers suffering orthopedic/neuromuscular impairments and handicaps from their war injuries. After finishing my residency I was assigned to Madigan General Hospital at Fort Lewis, Washington. I saw and treated many of the returning Vietnam soldiers who had suffered traumatic orthopedic and neuromuscular injuries. Here is a photo of me taken at our quarters at Fort Lewis holding my one year old daughter, Jennifer, now the wife of Dan McHugh (photo 18)!

18 Major Joe Pryor - U.S. Army Medical Corps

One of the unique cultural characteristics of the Ozarks is the preservation and continuing enjoyment of the musical traditions which our forefathers brought with them as they migrated here from various locations of the eastern part of our country. Many opportunities abound in our area to listen to the various musical groups which play and sing the old time music of the last several generations. For example, every Wednesday from 11:30 a.m. until 2:30 p.m. you can enjoy the live music of local musicians at the meeting room in the Eldon McDonald's Restaurant. The number and make up of the musicians vary but you can be guaranteed you will hear old time music enjoyed by generations of Miller County citizens through the years. Usually, you will find Joe Jeffries playing the standup bass and Clifford Hill playing the fiddle but many others are regulars also. The other day when I was there I took this photo of the group (photo 19):

19 Eldon McDonald's Wednesday Musical Group From the left are David Cotton, Bill Reagan, Gary Tucker, Clifford Hill, Joe Jeffries, Don Upton (foreground), Steve Mossman (rear in front of window), and Gail Workman. The meeting room is large and you can sit at the table and enjoy your hamburger while being entertained for free!

Others musicians come on Sundays including Gary Williams on guitar and Judy Smith playing hammer dulcimer. Last Sunday I took this photo of that group of musicians (photo 20):

20 Eldon McDonald's Sunday Musical Group From left to right are Kevin Kennedy, Joe Jeffries (playing bass), Amber Byrd, Judy Smith, myself, Gary Williams, Al Cates, Clifford Hill, and Francis Proctor.

Joe Jeffries has been a real friend of our museum as he and his group often have provided musical entertainment for the various events we have sponsored over the last few years. When he is playing at the museum we certainly have large crowds and they stay put in their chairs until the last song is performed! And Joe always provides his group to us without charge; he is a real supporter of our Miller County Museum!

A number of weeks ago I wrote the story of the flooding of the Osage River basin by the construction of the Bagnell Dam in 1931. As I wrote then, although the Lake through the years has provided the surrounding area with many opportunities for businesses and the jobs they bring, many do not know or remember the hardships caused to the original people who lived within the water shed of the Osage River covered by the Lake. Most were forced from their homes and farms to have to seek shelter and find a way to make a living elsewhere. You can read about that forgotten history of the Lake at this previous edtion of Progress Notes.

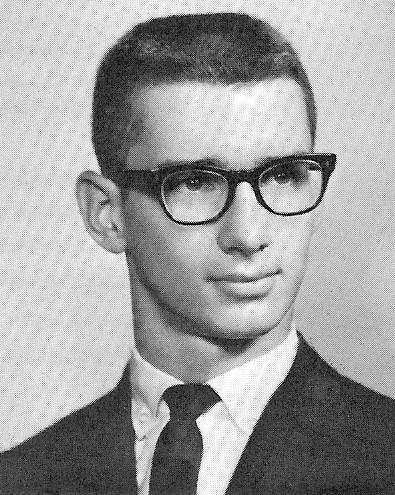

Tim Pilkington, who was raised in the Lake Ozark area and was graduated from the School of the Osage in 1963, heard his mother tell many stories of her memories of those days of the trauma the dislocation caused many of the local farmers and residents of the Osage River valley above the dam. These stories made an impression on Tim and inspired him to write a fictional play titled The Cricket’s Song about this little known period of time in our local Ozarks area history. A short biographical sketch about Tim and his idea to write the play was sent me recently:

Tim Pilkington is a native of Lake Ozark and graduated from the School of the Osage in 1963. In 1990, Tim, his wife Carole and daughter Christina, moved to Florida, where they currently live in St. Cloud.

The Cricket's Song was written in 1987-88 and produced by the Lake Area Performing Arts Guild in the Spring of 1988. Tim's mother and her five siblings grew up in Bagnell before and during the building of Bagnell Dam. "Growing up,” Tim says, “I would pay attention to the many stories they told of that period. It fascinated me and so I wrote about it."

Semi-retired, and "threatening to start writing again", he will, he says, "as soon as I can come up with the first three words of the first sentence!"

Tim was an outstanding student at School of the Osage from where he was graduated in 1963. Here is his graduating class photo which I got from my wife Judy’s copy of the 1963 “Pow Wow,” the official school annual of the School of the Osage (photos 21 and 22).

21 Tim Pilkington - 1963

22 Pow Wow - 1963 And here is a list of Tim’s accomplishments at School of the Osage as printed in that edition of the Pow Wow which was Tim’s senior year:

Tim Pilkington

Student Council Officer 4; Class officer 1,2,3; French Club 4; officer 4; Drama club 1,2,3,4; Pow Wow editor 4; Square Dance Team 2,3,4; One-Act play 2,3,4; Speech representative 3,4; Choral Clinic 3; Injun Antics 1,2,3,4; Three act play 2,3,4; Basketball 1,2; Football 1,2,3,4; Explorer Scouts 2,3,4; Track 3; Indian Dancer 1; Pep Club 3; Track 3; Indian Dancer 1; Pep Club 3; Debate Team 3; All Conference Football Team 2,4; Planned Progress 2,3; State Play Contest 2; Drama Club life member 3; Lebanon Speech Tournament 3.

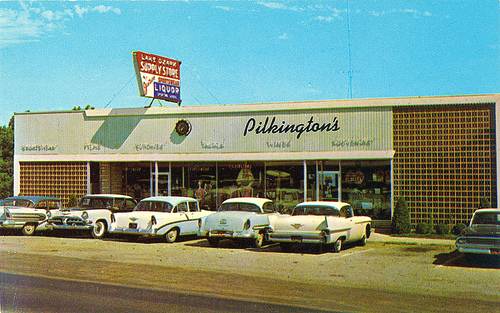

Tim’s parents were Harold and Theora Pilkington who for many years owned and operated The Lake Ozark Supply Store which was located on the “Strip” at the Bagnell Dam (photo 23).

23 Pilkington's at Lake Ozark Tim gave me permission to let our website audience have an opportunity to read his play. I will place it on the website in serial fashion. Each week one scene will be uploaded to the site over the next eight weeks. The scenes will be collaged together and you can read each page by clicking on the individual page in the collage.

The Cricket’s Song

By Tim Pilkington

Act One - Scene One (photos 24 - 46).

Just click on any of the photo thumbnails to view a larger image.

Note: Once you click on an image below, a new window will open. It would be best to maximize this new window by clicking on the middle box in the upper right-hand corner of the window. When you move your cursor over the image in this new window, it will change to a magnifying glass. Once this occurs, click on the image and it will show in a larger format for easier reading.

That’s all for this week.

Joe Pryor

|