|

Monday, May 25, 2009

Progress Notes

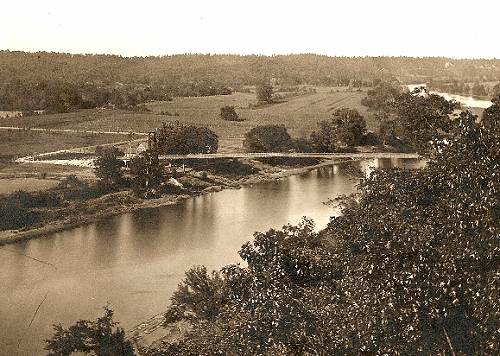

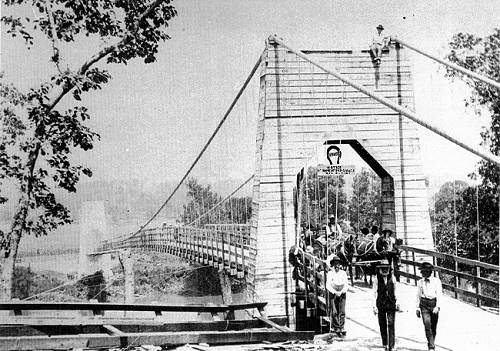

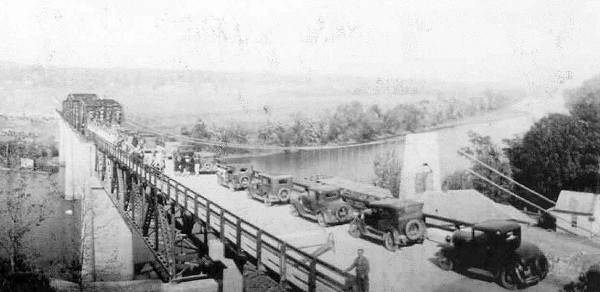

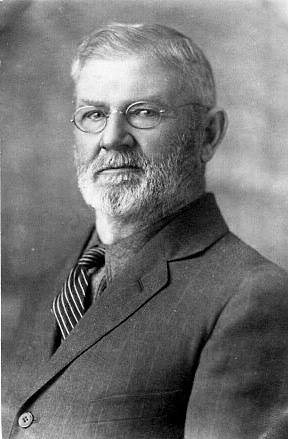

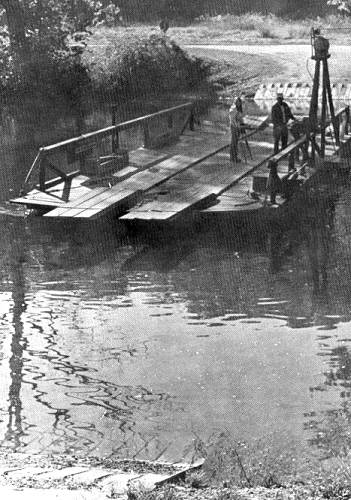

Recently, Ginnie Duffield of the Vernon Publishing Company interviewed Jack Edward of Tuscumbia (photo 01) regarding his memories of the old swinging bridge (photo 02) which crossed the Osage River and was in use before the present but soon to be replaced bridge was built.

01 Jack Edwards

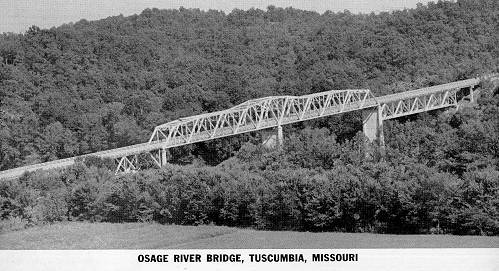

02 Suspension Bridge from the North Here is a photo of the present bridge soon after it was built in 1933 (photo 03):

03 Osage River Bridge The interview was published in the Tuscumbia Autogram Sentinel May 7, 2009. Many of the readers of this website may not live in this area nor have access to the Autogram so I though they as well as others who hadn’t read it would appreciate the opportunity to do so here. The subject is a timely one due to the rather constant running conversation among locals about the progress of construction of the new and third Osage River bridge:

THIRD BRIDGE IN A LIFETIME

BY GINNY DUFFIELD

The Miller County Autogram-Sentinel – Thursday, May 7, 2009

Jack Edwards’ memories of the old toll bridge at Tuscumbia are those of a young boy who got to go to town with his Daddy. But they are indelible. The old suspension bridge, constructed by the legendary Joseph Dice in 1905, was replaced by the current bridge in 1932. The 1932 bridge currently is being replaced and will open sometime in 2010 and plans are already being made to have Edwards be the first person to cross it on opening day.

“I rode across it with a team and a wagon...I was a little feller,” Edwards said this week. It was an exciting time for Edwards every time he went. “I got to go with my Daddy...We went to the mill every little bit,” Edwards said. The trip with the team and wagon was from the family’s river bottom farm to the old Anchor Milling Co. roller mill, located in the bottom, or “under the hill,” in Tuscumbia on the other side of the Osage River.

During World War II, the company moved the last of its operations to a site along Highway 52 in Tuscumbia because of a devastating war-time flood. The company is now closed and its Tuscumbia site includes the building constructed during the war of local materials and now houses the Miller County Historical Society Museum. A bail bonding company and the Miller County Courthouse and Jail complex occupy the remainder of the company’s former site. One of the buildings located in the bottom is in private hands and serves as a residence but the roller mill building is gone.

Horses did not like the suspension, or swinging bridge, Edwards said. “You had to make them go. They’d kind of creep across it,” he said. “When the wind was out of the east, it was awful rough. It (the bridge) would swing four or five feet,” Edwards remembers (photo 04).

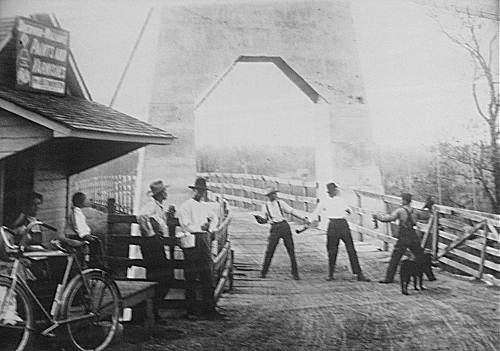

04 Tuscumbia Bridge 1905 - 1933 The bridge was a toll bridge, with a small house on the south, or upper, end. Edwards said he can remember his father “pitching the money up on the toll house porch.” He thinks the toll was a quarter (photo 05).

05 Tuscumbia Swinging Bridge In addition to using teams to travel between home and town, the family also had a Model T Ford and sometimes made trips in it, Edwards said. Some older men said when they were dating, and had to cross the toll bridge to get their young lady home, they wanted to be sure to get across the bridge before the toll keeper went to bed because he was likely to charge them more if he had to get up. “I never had that problem. I was too young,” Edwards said.

“I remember him (the toll keeper) sitting there on the porch, ‘rared’ back in a chair,” he said. Edwards remembers the current bridge being constructed and what a great thing people thought it was. But he is sure he was not among those who made the inaugural trip across then new bridge in 1932, as pictured in the next photo (photo 06).

06 New Bridge and Old Bridge He has made thousands of trips across it since, including at least once on horseback. Just because there was a new state bridge at Tuscumbia in the 1930s did not mean the travel with teams and wagons ended. The Tuscumbia farmer remembers he once was sent horseback on a mare to Harrison’s Stud Service on the other side of the Osage. “Everything was team and wagon back then,” Edwards said. Farming was done with teams, too.

It could be disheartening to farm in the river bottom, despite the fertile soil. Edwards said he has seen some terrible floods, including that war time one. “That was a big one. I can’t remember all of them.”

The peak of that flood on Lake of the Ozarks was May 22, 1943, when the reservoir reached 665.45 feet above sea level, nearly five and a half feet over full reservoir according to old Union Electric records. Excess water would have been flowing out of Bagnell Dam long after that, flooding river bottom fields during the best part of the growing season (photo 07).

07 Tuscumbia Flood If crops were destroyed and there was time to make a crop, farmers replanted. “I’ve seen as many as three different corn crops made in one year,” Edwards said. That’s (growing corn) about the only way we had of feeding our hogs.” Sometimes the “catch crop” was planted pretty late because the grain was needed and getting a harvest had to be tried, Edwards said.

Edwards no longer lives in the bottom. He and wife Dean live on the uplands now. “I bought me a ridge farm,” Edwards said. “It’s been a good life.” But the river still had its attraction, one of the loves he learned from his father John – fishing. He remembers an uncle, who was grubbing out thistles and mulleins from his field, telling his father that if he would do the same, they could be rid of the weeds. The reply from his father was, “The Good Lord put them there. We’re going fishing.”

At age 82, Edwards hopes to see the new bridge completed and has been watching the construction.

“They’ve moved a lot of rock there... It makes good material,” Edwards said (photo 08).

08 Bluff Removal - 11 May 2009 He also thinks progress is so rapid, the builders will beat their September 2010 deadline. Edwards is looking forward to the trip across the third Osage River bridge at Tuscumbia in his lifetime.

You can read about the celebration event honoring the new construction of the 1933 bridge (still our present one thus far) at this URL on our website:

http://www.millercountymuseum.org/events/bridgededication.html

The history of the ways the Osage River was crossed at Tuscumbia is tied in many ways to the development of the town itself. This subject was written about many years ago in the Autogram in 1933, probably in conjunction with the opening of the present bridge, which I will copy here. The article was taken from a saved newspaper clipping donated to the museum but is missing the name of the author:

Tuscumbia Autogram

2 November 1933

Ninety six years ago the town of Tuscumbia was “put on the map” by the platting into lots the land where the present town site is located; and in December of 1837, the same year the town was platted, a post office was established here, with M.P. Harrison as the town’s first postmaster.

Forty acres were donated to Miller County by the Harrison brothers, J.P. and J.B. with the understanding that the county seat would be established here. But even before the coming of the Harrisons there was an Indian trading camp here, and a good ford was accessible at this point. Then the canoe was the sole means of crossing the stream when the water was too high for fording. With the white man came the flatboat which was propelled either with pole or oars and for many years ferrying was done her by that means.

Tuscumbia soon became a great trading point, people coming here from all sections of this and adjoining counties to the west and southwest. Warehouses sprang up on the north and south banks of the Osage, and flatboats, loaded with merchandise were poled up the river laboriously by white men. Caravans came here from southwest Missouri and merchandise was shipped by ox team and wagon to Springfield and other southwest points, this being a terminus for water transportation much of the time. That was before the advent of the railroad.

Our oldest residents recall that the ferry boat antedating the cable ferry was operated by two large oars, one on either side of the boat, and each oar was operated by two men. Then a third man handled the steering oar at the end of the boat. In order to make the landing on the opposite side, it was necessary, when the river was high, to row the ferry boat upstream along the bank some distance before striking out across the river.

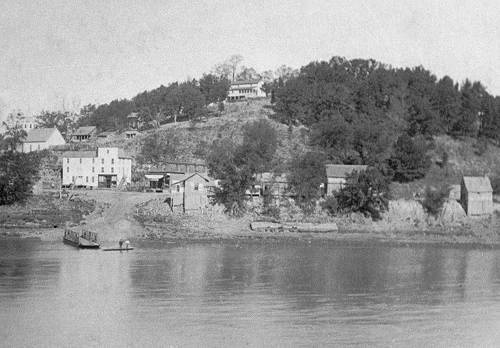

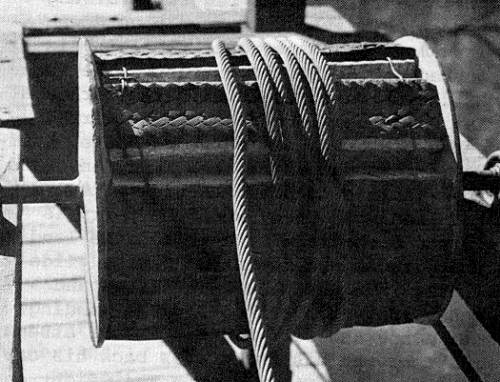

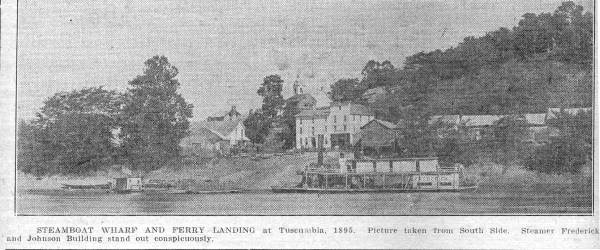

About the year 1880 a cable ferry was inaugurated here (photo 09).

09 Ferry Landing at Tuscumbia This cable was about one inch in diameter and was suspended across the river, over the top of supports 15 feet above the bank. The south end of the cable was stationary, but the north end was fastened to a windlass, which by means of a sweep, operated with man power, would wind up the cable to the proper tightness (photo 10).

10 Ferry Windlass A heavy chain was fastened to the end of the cable and a pin through one of the links held the cable. When steamboats approached the cable for passage up or down stream, it was lowered by knocking the pin out of the link and the cable fell with a splash.

At each end of the ferry boat was an apron, which was lowered when the boat landed so that a vehicle or stock could get loaded more expeditiously. At each end of the boat, which was about 40 feet long, there was also a windlass, and these windlasses were connected with the cable by means of two pulleys which traveled along the cable. By this arrangement, one end of the boat could be pulled up stream higher than the other, and the current pushing sidewise against the boat would propel it across the stream. This was hailed as a great invention and was really a big improvement over old methods.

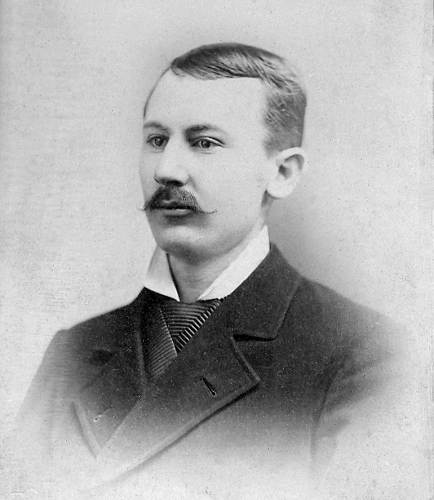

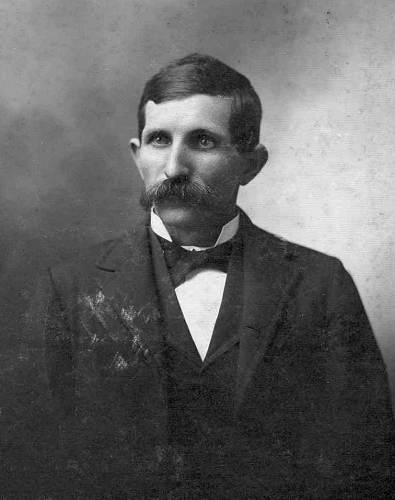

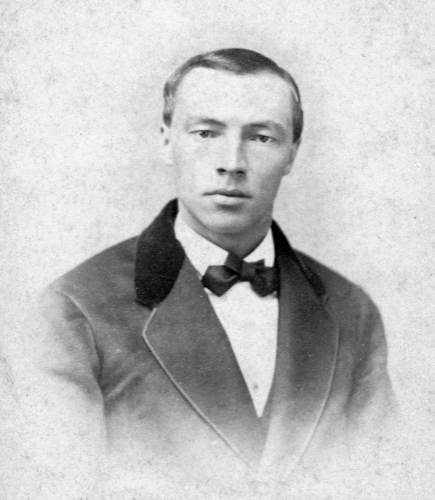

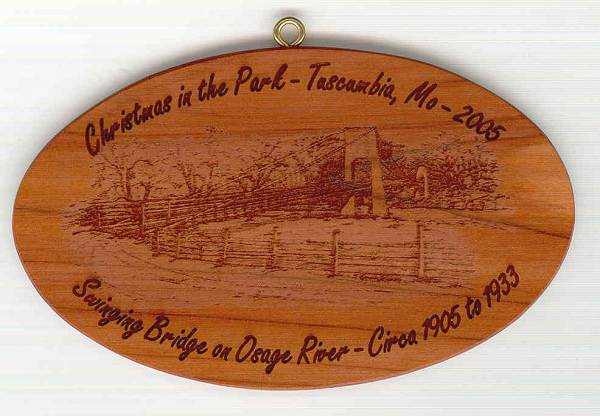

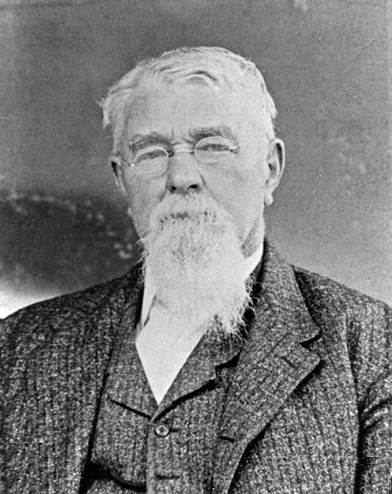

This served for about thirty years, then in the latter part of 1904, Mord McBride, Captain R.M. Marshall (photo 11), J.R. Wells (photo 12), G.T. Hauenstein (photo 13), Captain W.H. Hauenstein (photo 14) and others became interested in a bridge here.

11 Bob Marshall

12 J.R. Wells

13 George Hauenstein

14 William H. Hauenstein, Jr. They got in touch with J.A. Dice, of Warsaw, whom they had heard was building practical “swinging” bridges. Some of them went up to Warsaw, and after investigation, one of Mr. Dice’s bridges at that place, decided to employ Mr. Dice to build a similar structure here. Ere spring arrived the plans had been worked out and on April 5, 1905, the Steamer J.R. Wells landed at the bridge site here with 106,000 pounds of wire, and work started the following week (photo 15).

15 J.R. Wells Steamboat After the towers were built, the stringing of wires for the cables began. Each cable contains 720 wires, each wire having a tensile strength of 1500 pounds. A wheel was improvised on the hill at the south end of the bridge. By means of an endless rope, a wire unrolled from the wheel which was drawn across the stream, then lifted up to the tops of the towers with ropes and placed on the steel plates on the top. The wire was then fastened to one of the steel pins imbedded in the concrete at either end of the bridge. The weaving of the floor support wires and stay wires consumed considerable time, and was of a hazardous nature. The main span of this bridge is 618 feet long.

On August 3rd and 4th, a grand dedication was held in conjunction with a picnic at the south end of the bridge. During the night Chinese lanterns illuminated the bridge, and fireworks were shot off from the bridge.

It will be of interest to our readers, especially the older citizens, to read the account by the Autogram of that demonstration:

“Seldom do people of Miller County attend a picnic with more pleasing results than the bridge dedication and two day picnic at Tuscumbia last Friday and Saturday. A prominent minster who was present asserted that the good nature and orderly conduct of those present made him think he was attending a Sunday School gathering, and that he never enjoyed himself better in his life. If we have a rowdy element in the county, it was not present. No disturbance of any kind…not even a quarrel…took place during the two days; everybody was good natured and happy, and the big bridge was the admiration of all who viewed it for the first time. The people here who have watched this structure slowly rise to completion do not all appreciate what the big bridge means to the people of the county. It is appreciated more by those at a distance than those at home. For more than 20 years the Autogram has advocated bridging the river here and we feel proud of the humble part we have taken in causing the dream to become a reality.”

But to return to the picnic: both days were ideal for the gathering, and the people poured into the grounds from every point of the compass. On Friday the crowd was estimated at from 1,500 to 2,000; on Saturday the number was easily doubled.

The Eldon Band came down Thursday evening and discoursed splendid music for two days (photo 16).

16 Suspension Bridge Dedication Ceremony Band - 1905

Click image for larger viewThere are few better bands in this part of the state and all of the members are gentlemanly fellows and made many friends during their stay in town.

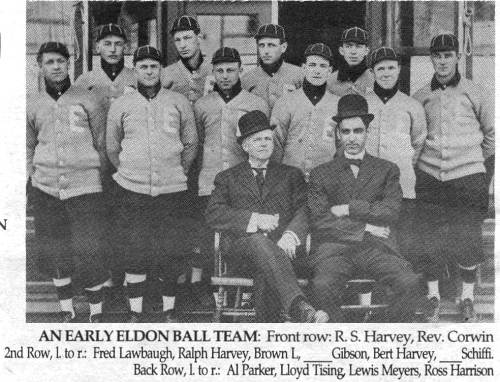

The Eldon base ball team (photo 17) came over Friday morning and were to have played the Iberia team in the afternoon; but for some reason not yet entirely clear, failed to fulfill its promise.

17 Early Eldon Ball Team

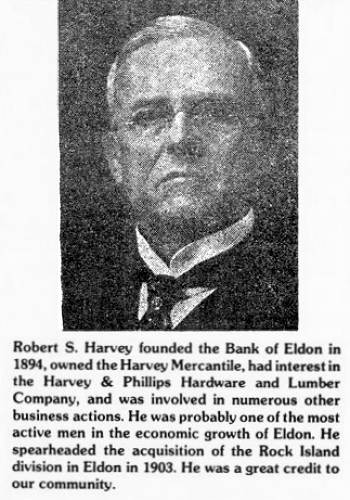

Click image for larger viewThis occasioned great disappointment among the lovers of the National game who came to see the Iberia boys give the Eldon champions their “money’s worth..” In this connection it is not out of place to thank banker Robert S. Harvey (photo 18) for valuable favors in arranging matters for the band and ball team to be present. Some men are born generous and broad minded, and Mr. Harvey is one of them.

18 Robert S. Harvey

Click image for larger viewHonorable Joseph W. Hunter of California, followed with a nice little talk. He thought the big bridge was a splendid structure and would be of great benefit to the people of Miller County. He said when McBride commenced agitating the bridge question he thought he was “talking through his hat,” but Joe forgot that the Autogram’s tow line was never known to break, no matter how many got onto it.

Friday night 200 Chinese fireworks were set off from the bridge banisters over a half hour time span and was witnessed by hundreds of people.

Saturday morning vehicles by the dozens commenced coming in to town, and by noon the crowd was estimated all the way from 3000 to 4000. But whatever the number, it was the largest crowd that has assembled at Tuscumbia in many years.

Here is a short paragraph about the suspension bridge from Schultz’s History of Miller County:

“In 1904, the citizens of Tuscumbia organized to build a wire suspension bridge across the Osage. The bridge was dedicated 5 August 1905. It was 620 feet long and 14 feet wide. It was built at a cost of $10,000. The bridge was used as a toll bridge until 1933 when it was replaced by a steel structure.”

From the Miller County Autogram, dated October 1, 1903:

“Citizens of Tuscumbia Organize to Bridge the Osage River With a Capital of $10,000”

"The stock was subscribed by the following in equal shares: Fred A. Goodrich, Walter S. Goodrich, Captain Robert M. Marshall, Joshua R. Wells, Mord McBride, W. Samuel Johnson, William Hauenstein, George Hauenstein, and Phillip Hauenstein.

The location of the bridge will be just below town (downriver from Tuscumbia). The three roads leading into town from the south side will be brought down to the bridge on top of the ridge, thus avoiding the old road across the river bottom altogether. People can then get to town at any stage of the water.”

Peggy Hake has written a short sketch about the principle investors of the suspension bridge:

Tuscumbia had experienced some devastating floods in the past, especially in the 1890’s. It appears the business men (mentioned above in the paragraph from the Autogram) wanted to do something to help decide the fate of their town, business places and homes. Evidently the nine men who were named in the article put up at least $1,000 each to get the new bridge built across the Osage at Tuscumbia.

The following is a small sketch about each man who helped to get the first bridge built across the Osage:

Mord McBride was the publisher of “The Miller County Autogram” and was also part owner of the Miller County Abstract Company in Tuscumbia. In 1900, he lived in the village of Tuscumbia with his wife, Lillian, and their eight children.

Captain Robert Melville Marshall (previous photo 11) was a former riverboat captain on the Osage and in 1903 was president of the Bank of Tuscumbia. He and his wife, Emma (Hauenstein), lived in their beautiful home near the banks of the Osage, located today south of Riverside Park.

Joshua R. Wells (previous photo 12) was a director of The Bank of Tuscumbia and was a prosperous farmer. His majestic home was built about a mile downriver from Tuscumbia and still exists today, although moved a few hundred yards up the hill from the original location in the early 1940’s (due to flooding of the Osage over the years). Joshua, his wife, Lucy (Lawson) and their five children were living on the Wells farm in 1900.

Phillip F. Hauenstein (photo 19) had been a riverboat captain on the Osage in years past and in 1903 was owner of Anchor Milling Company near the banks of the Osage River, under the hill, in Tuscumbia. In 1900, Phillip, his wife Sally, and their four daughters were living in Tuscumbia.

19 Phil Hauenstein George T. Hauenstein (previous photo 13) was a general store merchant in Tuscumbia at the turn of the century and also served on the board of directors of Bank of Tuscumbia. George and his wife, Ida, lived in Tuscumbia during the census taken in 1900.

William A. Hauenstein (previous photo 14) was part owner of the Miller County Abstract Company and was cashier of the Bank of Tuscumbia. In 1900, William was living in Tuscumbia with his wife, Martha (Challes) and their three children.

Fred A. Goodrich was a resident of Tuscumbia but I do not know if he was a business man. The Goodriches were once prosperous farmers south of the Osage River. His father, Isaac Goodrich, was an early Miller County official, holding the office of assessor, circuit clerk and judge. The father was also a newspaper publisher.

Walter S. Goodrich was a brother of Fred and another son of Isaac. Walter, his wife Fannie, and two daughters lived in Tuscumbia in 1900. The Goodrich family lived in the state of New York before coming to Miller County.

W. Samuel Johnson was a resident of the village of Tuscumbia during the census of 1900. He and his wife, Susan, had four children in their home during that census. I do not know if he was a business man or just a citizen of the town.

A new suspension bridge was indeed built and was dedicated at special ceremonies on August 4 and 5, 1905. It was the first bridge built to span the mighty Osage in Miller County. In the many years preceding the bridge a ferry was used to get folks from one side of the river to the other. The suspension bridge, also used as a toll bridge, was in existence until 1933 when the present bridge was built. The old bridge was just a short distance downriver from the new, more modern structure constructed in 1933.

Just as Jack Edwards recalled his memories of the old suspension bridge, others have also. One of these was Doris Wright Clemens (photo 20) as quoted from a previous edition of Progress Notes:

20 Doris Wright Clemens “To get to and from school (Bear School) south of the river, I walked. Sometimes my father took me in the car to the river bridge. There was a fare to cross it, so we didn't cross in the car but I walked across. The bridge was the longest suspension bridge in the state. It had its own rhythm as it hung suspended over the Osage River. A cat walking across this bridge could cause it to shake up and down until one could hardly stand up on it. Arriving at the far end of the bridge, I descended a very steep bluff on steps worn out of the rock and walked across a grassy area, flat river bottom, to the foot of a high hill. Sheltered here was the tent the Varners lived in.”

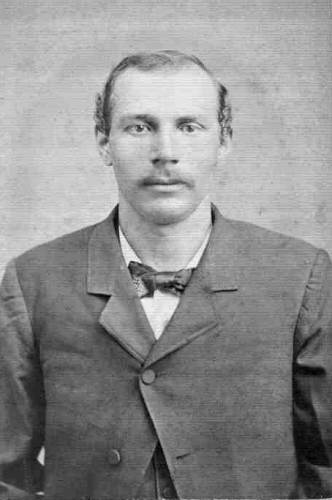

Another memory is that of David Bear (photo 21) who was born on a farm which still belongs to a member of the Bear family on Dog Creek one mile east of Tuscumbia:

21 David Eli Bear "Rivers can be obstacles to land transportation. The early settlers had to deal with crossing streams to reach their destinations. Also the settlers on the south side of the river from Tuscumbia needed to get to town occasionally to buy and to sell. In the summer, there was usually a few shallow places where the river could be forded, but for year round transportation, a ferry was operated. The landing was near the present boat ramp n town. To do a better job of helping the public, a private corporation built a bridge in 1905. This was a suspension bridge with just one lane. In approaching the bridge, one had to watch carefully to see if someone was coming across from the other side. Once on the bridge it was difficult to back up a team of horses. The gatekeeper also helped keep watch. A toll charge was assessed for crossing. My memory is that it cost fifteen cents for a team to cross. Later, the charge was twenty five cents for automobiles.

I remember the bridge very well. It was scary for me. It would swing in the wind and the wood planks made quite a noise. It was scary to walk across because of the height from the water and the swaying of it. My brother in law, Bob Stillwell, while on summer vacation from college, helped paint the bridge one summer. All the money in Miller County couldn’t have enticed me to do that job.

Arthur Ewing was the toll keeper for many years. He lived in a shack on the south end (previous photo 05). If he didn’t want to stay up all night, he locked the gate to keep people out. He took the proceeds to the bank weekly and always carried it in a gallon syrup bucket to camouflage his activity. Everybody knew what he was doing."

Sometimes patrons of local businesses were given a token to give to Mr. Ewing to allow them to cross the bridge free. Here is a photo (photo 22) of one of those tokens given out by the Anchor Milling Company.

22 Anchor Mill Token for Suspension Bridge I received this token as a donation to the museum from Bamber Wright, one of the last owners of the mill.

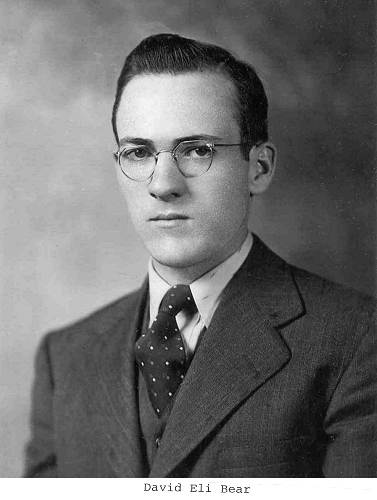

Also of interest is this laser engraving on a native cedar wood plaque depicting the old suspension bridge done by Tommy Snodgrass, who lives across the road from our museum (photo 23 of engraving).

23 Cedar Wood Memoriam

But as noted above in the old Autogram article above, written in 1933, the ferry was the first means of crossing the Osage. Several ferries were used at different locations on the Osage in our area through the early years. Peggy Hake has summarized those locations in the following essay which was taken from our website:

http://www.millercountymuseum.org/communities/fairplay.html

Ferries on the Osage

By Peggy Smith Hake

The Osage River has played a very important part in the history and development of Miller County. When the first pioneers came into the area there were only old trails that had been used by the Indian tribes who lived and roamed the hills, valleys, and prairies of the county. The river was navigated by canoes and flatboats and eventually riverboats, which carried people, animals, supplies, and equipment up and down its waters. As settlers began to move into the area, these rivers had to be forded to settle outward in all directions. Everyone who came into Miller County could not settle along the riverbanks. The expansion had to go both north and south of the river.

Small settlements were established along the banks of the Osage and ferryboats were used to get the people from one side to the other. According to the county's recorded history, the first ferry was built in the early 1830s just above where Bagnell Dam is now located in Franklin township. The second ferry was established at Brockman Ford, downriver from the first one. The third ferry was located at the "the western ending of the Old Blue Tail trail, owned by T. O. and T. G. Witten". I am not sure where the 'old Blue Tail trail' was located in Miller County.

The fourth ferry was established at Harrison's Landing (today's Tuscumbia) in the mid 1830s. This old settlement was a trading post built and operated by John B. and James P. Harrison, brothers who came from Phelps County, Missouri. The fifth ferry was established in Jim Henry Township about 1839 on the west side of the Osage on land owned by John S. Witten. It was given the name Fair Play and was a frontier settlement with a storehouse and a ferry crossing.

Life was at times dangerous on the Osage River and the ferry boat once in a while encountered hazardous situations causing loss of life and serious injuries. This especially occurred in high water but also the nature of the loads carried could cause risk as well. The following is an old article from the Autogram detailing some of these events:

The Miller County Autogram, Tuscumbia, Missouri

Thursday, November 2, 1933

Quite a number of exciting episodes and tragedies transpired at the old ferry landing (photo 24).

24 Ferry Landing Photo

Click image for larger viewAmong these might be mentioned:

1. The double drowning May 14, 1866, when T.P. Barrett and Richard Higgins lost their lives while assisting in the raising of the ferry cable;

2. The capsizing of the ferry boat, August 26, 1890, when John Weitz, Bob Sullivan and William Witt narrowly escaped with their lives and 31 head of cattle drowned;

3. and the accidental death of William Witt, the ferryman, February 23, 1891.

4. The fatal shooting of Alec Colvin occurred on the south bank of the river in the nineties when Colvin was assaulted by the Williams brothers as he was going home from town.

Following is the Autogram account of the drowning of Barrett and Higgins:

“A sad accident occurred here last Friday morning (May 14, 1886) at about 9:30 o’clock which cost the lives of two of our citizens and cast a gloom over the quiet little city when it was announced that T.P. Barrett and Richard Higgins had been drowned in the river by the capsizing of a skiff. The Gram reporter was soon on the spot and from eye witnesses to the sad scene, we gathered the following particulars, which are about correct: Friday morning had been set by Mr. Johnson as the time for re laying his ferry cable which had been torn loose from its fastenings on the north bank of the river by driftwood during the recent rise…and it was decided that the best way to do this was to use the skiffs…four in number..as a sort of buoy to hold the wire out of the water while the Steamer Frederick (photo 25) was to tow the lower end of the line to the north bank of the river.

25 Steamer Frederick at Tuscumbia Landing Barrett and Higgins occupied the skiff next to the Frederick. None of the other skiffs had occupants. The position of Barrett and Higgins’ skiff was about third way across the river from the south bank. Both men were sitting in the bow while the cable lay across in front of them. They were advised by several to get on the boat as their skiff might sink, but Mr. Barrett thought not and jokingly remarked that they would have a good ride, and kept his seat.

The engine was set in motion which, together with the force of the current against the wire, caused the bow of the skiff to sink without warning to the occupants and the next instant they were both thrown into the river, and it is the opinion that they were disabled by the wire striking them when the skiff capsized. They were excellent swimmers and notwithstanding the fact that they wore very heavy boots out and headed for the south bank, swimming high, and everyone thought they would reach shore safely. Suddenly, they seemed to lose their self possession and commenced drifting out farther into the river. Mr. Barrett gave way first and disappeared; he rose immediately and sank to be seen no more. Mr. Higgins was some distance in front of Mr. Barrett and was struggling manfully. At this time Captain Marshall was making heroic efforts to get to the men with the Frederick, but the swift current made his efforts fruitless.

Mr. Higgins was urged to keep swimming, that help would soon be there. He replied that it must come soon as he was almost exhausted. Looking back he saw Mr. Barrett’s hat floating towards him, and giving one agonizing cry for help, sank beneath the water.

No one in particular is to blame, and no one more deeply deplores the sad affair than does Mr. Johnson; and he will spare no expense that the bodies may be recovered and delivered to their families.

Mr. Barrett leaves a wife and three small children almost wholly unprovided for, and Mr. Higgins a wife and two children who were dependent upon his daily labor for support. Both were hard working, peaceable men, attending strictly to their own affairs, and leave a large circle of friends who could not speak other that words of praise in their behalf.

Later the body of Mr. Barrett was found by J.W. Hargraves on Monday, about 11 miles below here near the “Devil’s Elbow,” lodged in a drift. James Clark, U.S.G. Todd and Marion Frazier started after the body about 4 p.m. of that day and got back at 1 a.m. Tuesday morning. The face was black and swollen almost beyond recognition, the body having probably been floating for some hours. The body was taken to the Clarke building where it remained until 11 o’clock and was then carried to the cemetery and interred.

It was August 26, 1890, when Wilson Brothers, extensive buyers of cattle, drove up a large herd from South Missouri at the south ferry landing seeking passage across the Osage.

Tom Johnson was still proprietor of the ferry, and he had Johnny Weitz in charge, with Bob Sullivan and William Witt assisting. Most of the cattle had been brought across. Forty three head of cattle remained on the south side. Mr. Johnson was standing on the north shore watching the operations, and when Mr. Weitz informed him from across the river that there were 43 more cattle to bring over, Mr. Johnson told him to put them all on the boat. The fateful order was obeyed.

According to a reliable version of the affair, the boat was a new one, about 50 feet long and had been used by Captain Robert M. Marshall with the Steamer Hugo in the transportation of wheat. Mr. Johnson bought the boat for the ferry. On one side of the boat was a guard, or walk way, out side the railing. For some reason, the side of the boat with this guard, which extended out from the boat, was turned up stream, and that was responsible for the capsizing. No sooner had the boat gotten well under way than the 43 head of cattle began milling about on the boat, crowding the upper side until the current caught the top of the guard. In an instant the boat had turned bottom side up. Sullivan and Witt escaped with little difficulty, but Weitz was caught underneath the boat between the banisters among all the cattle. He was almost drowned before he could extricate himself. He finally freed himself and came up near the side of the boat and was dragged up by his companions on top of the capsized boat, where he fell in and exhausted condition.

Thirty one head of cattle valued at $620.00 were drowned, and the damage to the ferryboat was $200.00. The carcasses of the drowned animals were towed to the bank and skinned, the 31 hides representing a small saving.

The Autogram gives the following account of the death of Mr. Witt, February 23, 1891:

William Witt, one of I.T. Johnson’s assistants on the ferry boat met with an accident about 3:30 Monday afternoon from which he died at 11 o’clock that night. The ferry boat is rigged with a windlass at either end of the boat for the purpose of heading the boat up stream. When the river is high as at present, these windlasses are very hard to work, requiring a strong man to handle them. The accident happened near the south bank of the river during preparations to return to this side. In turning the windlass the iron handle slipped out of his hand, and coming over struck Mr. Witt almost on the top of the head, crushing the skull fearfully. He was taken into Johnson’s drug store where Dr. McGee (photo 26), aided by many kind hands, dressed the terrible wound.

26 Dr. James McGhee Before this was completed the injured man became unconscious, and remained in that condition until death.

Finally, an excellent article on Missouri Ozark ferries was published in the Bittersweet magazine several years ago. It records the history of ferries on the Current River including much interesting information and photographs:

A Ferry Tale

A FACTUAL ACCOUNT OF OLD-FASHIONED FERRIES

Story by Linda Lee, Drawings by Kyle Burke

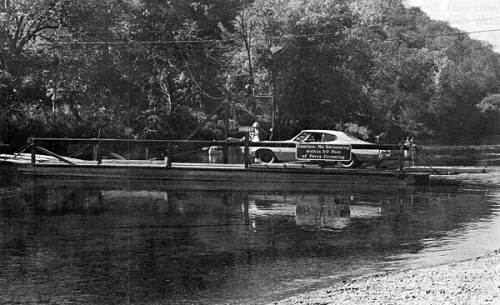

With the widespread use of the automobile in the Ozarks, ferries (photo 26a) instead of fords became the common method of crossing small Ozark rivers.

26a Moore's Ferry on the White River

Photo courtesy Townsend Godsey from OZARK MOUNTAIN FOLKMoore's Ferry on the White River, pictured above about 1943, used the river current for power and cables to hold it in place.

CURRENT-POWERED FERRIES

Dawn is just breaking & a car pulls up to the river crossing. As the driver waits for the ferryman to come out and take him across the river, he impatiently toots his horn, introducing a foreign sound into the quiet, fog-shrouded valley. The sound of the horn brings the countryside to life--both in the valley as the startled birds chirp frantically, and in the house, where the ferryman gets out of bed, knowing that it is the start of a long day.

This early morning scene happened many times at the ferry locations on the Ozark streams from the early 1900's to as late as the early 1960's. Since most of the rivers in south central Missouri are not very wide and narrow frequently over riffles shallow enough to be easily forded with horses and wagons or buggies, ferries were not needed nearly as much before the automobile era. The roads and trails led to the fording places which were spaced every few miles. In normal weather the streams posed no travel difficulty for horses. However, the automobile did have difficulty crossing the fords. The narrow wheels got bogged down in the gravel or mud bottoms. If the ford had any depth to it, or the water 'raised any, the engines would flood out. The ford crossings became such a problem that often the nearest farmer was literally kept busy pulling people out with his team.

Obviously as more and more people got cars, there was a demand for better crossings. Where bridge construction was too expensive, the solution was a current-powered ferry as near the original ford location as possible. So for many years, until the crossing was abandoned or a bridge built, ferries operated on many streams including the Current, St. Francis, White, Gasconade, Eleven Point and Niangua.

However, certain conditions had to exist before the ferry would be successful and not everyplace had a ferry where there was once a ford. First, the ferry had to be on a main-traveled road with enough traffic to make the operation financially successful. The approach and banks on either side had to be suitable for automobile traffic and landing points for the ferry. Above the flooding point on either bank, there had to be something permanent, either a tree or post, on which to fasten the cable that held the ferry in the river. The river had to be at least three or four feet deep to float a loaded ferry and the current had to be strong enough year-round to provide the power to push the ferry across the river.

Getting up at dawn was just one example of the confined life of the ferryman of past days, as he had to be on duty twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, year-round. He never had any time off unless he could hire somebody to run the ferry temporarily. Some ferrymen, during especially busy summer seasons, even put a cot out on the ferry. If a customer came along blowing his horn at two in the morning, the ferryman would get up, take him across, go back to bed and sleep until someone else would blow his horn.

Often running the ferry was a family operation. At many crossings, since traffic alone wasn't enough to provide a living for the ferryman and his family, ferrying was combined with other businesses. Since everyone on both sides of the river for miles around had to cross the ferry to go anywhere, the crossing became a good location for a country store, a mill or a blacksmith shop. As the community grew, the post office was usually located in the store at the ferry.

There was much more to ferrying than just taking the boat back and forth across the river. Many crossings were under the jurisdiction of the county court. In that case, each year he paid a ferry fee of about ten dollars to operate the ferry. He was sometimes responsible for building the ferry in the first place, and he was always responsible for keeping it in running condition and seeing that the approaches were maintained twenty-four hours a day. Then, the fare money that he received for the crossing was his.

It would be difficult to estimate the income of a ferryman. Euel Sutton said, "In the summertime, in the peak of tourist season, it was quite a bit, but in the wintertime, there wasn't many customers. And if the roads were bad, you didn't have any traffic. There was no way you could get a count to average it."

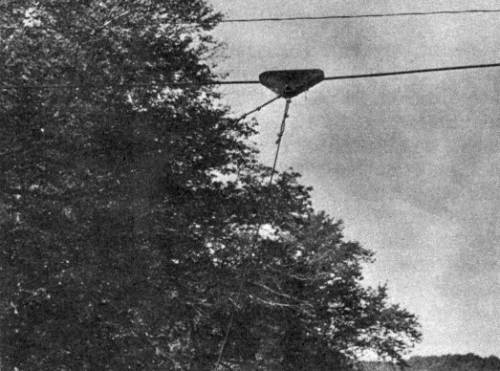

Modern motorists still cross the Current River at Akers, which is in the Ozark National Scenic Waterways, in a wooden ferry approximately 48 feet long by 18 feet wide (photo 26b).

26b Crossing the Current River Notice the cables across the river and the triangular pulley, all of which help guide the ferry and hold it in place.

Mr. Sutton remembered that when they first started the Powder Mill Ferry on the Current River, it cost ten or fifteen cents a vehicle to cross, "And if the customer didn't have the ten or fifteen cents, then some of the local farmers, if they were there with a loaded wagon, could bring potatoes, turnips, peaches, apples, whatever he wanted, and they'd trade them for the crossing. Kind of a barter system. Then as time went on and more cars got on the road, the fare went to twenty-five cents per car per trip of a daytime. Then of a night when you had to turn your lights on, it went to thirty-five cents.

"World War II came along, and then gas rationing took place, so the price stayed up all through the war. Then in '46, '47 traffic became a lot heavier, so they finally started raising the price, and then as the years went by, the car was seventy-five cents and a truck was a dollar because of the heavier load, and a dollar of a night."

Some ferries changed hands fairly often. The operators expected to earn more money than they were able to make. When they had trouble making ends meet, they sold out.

One ferry we found still operating was at Akers in the Ozark National Scenic Riverways. The ferryman there has a much easier life than the old-time ferryman. To cross the ferry, the motorist rings a bell. Someone in the nearby store answers the call, or on not-so-busy off-season days, one of the men working there in the store or at the canoe rental business on the bank takes the car across. Today's customers, not used to waiting, sometimes curse or bawl out the ferryman if he is slow to get there, as undoubtedly did customers in times past. The ferryman must develop a thick skin, ignoring them as he prepares to cross. Though the ferry is built with an oar-board to use the current power, to make the Akers ferryman's job still easier, the ferryman makes use of an electric motor to scoot the ferry across the river and another motor to pump out the water from the hull.

The design of the current-powered ferries was not complicated. They were constructed of wood at the crossing site. Depending on the traffic, they were made just long enough for either one or two cars and usually just wide enough for one car. They were floored over, flat-bottomed floating hulls, designed so that they did not float very deep in the water.

The framework of the hull was the gunnels. These were usually four wooden planks eight to ten inches thick, about two to three feet deep and as long as the ferry--some about twenty-five feet long. The gunnels were sawed at a slope on each end for approaching the bank. Since the ferry did not turn around, each end was identical. Held in place With supports, they were boxed in all around to form the hull, and the boxing boards were caulked to be watertight. Then the two by six floor boards were laid.

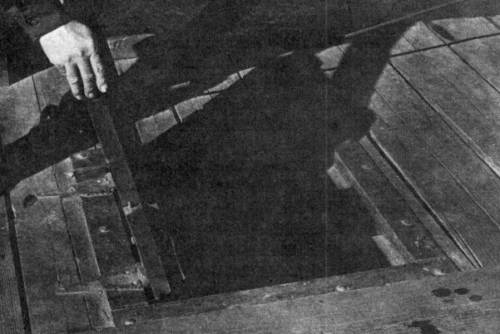

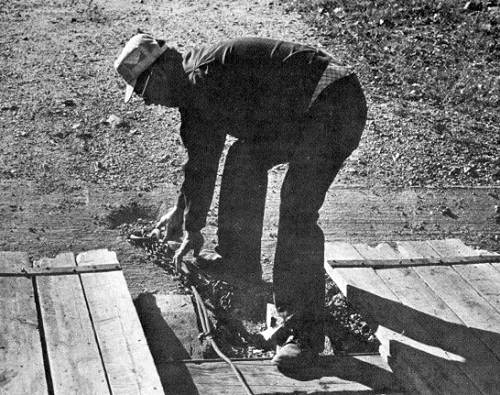

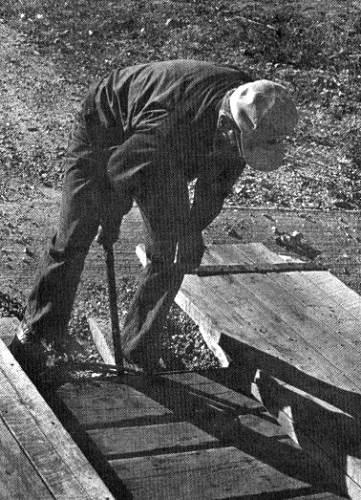

Because it was impossible to completely waterproof the hull, three by three trap doors were built into the floor to allow the ferryman to get in and scoop out the water with a shovel. He didn't allow water to accumulate to add more weight to the ferry and make it ride lower in the water. The trap doors also allowed the ferryman to get inside the hull to work on the bottom of the ferry, repairing leaks or punctures.

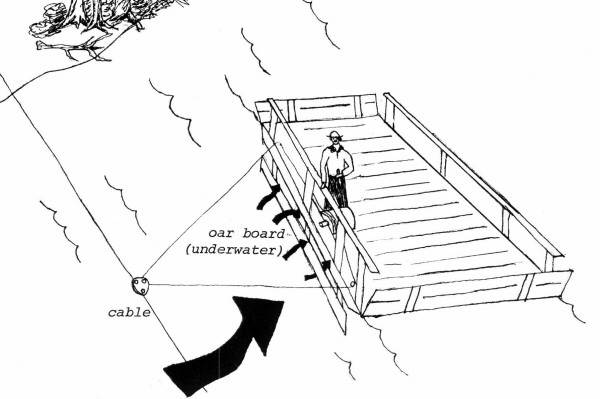

Fastened below the upstream gunnel was the oar board. The oar board, made usually from a two by six, was held in place several inches below the gunnel by supports.

At each end of the ferry, there was what was called a wing or apron. These were hinged to be raised or lowered, depending upon which bank the ferry was approaching. In the stream they were usually both up, though not all ferrymen raised them. When docked, the appropriate wing was lowered. Sometimes ferries had loading ramps or boards built on the wings which actually lay on the bank to make it easier for the car to drive on the ferry.

Along both sides of the ferry there was a precautionary railing about three feet high. These were usually just a few posts holding boards, rope or wire.

The several trap doors in the floor of the ferry enable the ferryman to get in the hull to scoop out water and repair leaks and punctures (photo 26c).

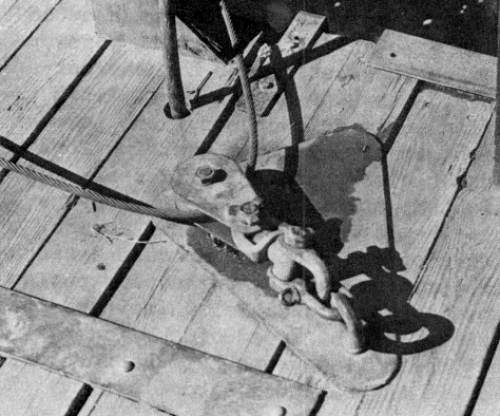

26c Trap Door To keep the ferry from going downstream, a continuous cable runs from the ferry through a triangular pulley on a main cable crossing the river (photo 26d).

26d Ferry Cables To secure the ferry to the bank, the simplest device was a rope or cable thrown over a stob in the ground or a handy tree. Some ferries had winches, pulleys and cables with a hook on the end. The winches used to tighten the cables, were in the upstream corner of each end of the ferry. A cable went from each winch to a pulley mid-point in the end and then off the ferry where the hook was fastened to a ring anchored on the bank.

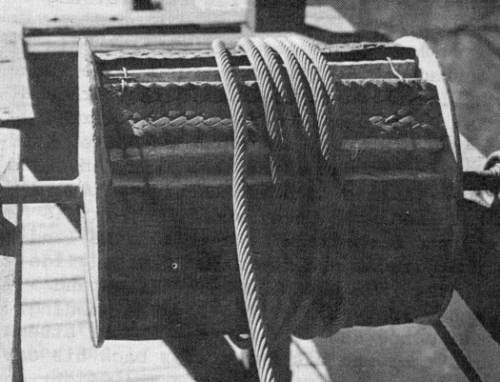

Besides the actual ferry itself, there was machinery to keep the ferry in place. Stretching across the river and fastened to a stationary tree or post on each bank, was the main cable, which was usually about 3/4th inch in diameter. The ferry was fastened to this big cable with smaller cables or lines. Riding along the main cable was a big triangular pulley, suspended with the point hanging down. A long continuous line ran through this point first to the pulleys anchored on each end of the ferry. Then from each end pulley, the line was wrapped several times around the windlass, located about mid-point of the upstream side of the ferry. The windlass was a circular wooden tub-like device about a foot in diameter with a handle to enable the ferryman to turn it. Turning the windlass would shorten one line and lengthen the other, thus pointing the ferry either upstream or downstream as needed to control the ferry in the current.

There are three basic operations in running a ferry. They are loading, crossing and landing.

To load a car onto the ferry, the ferryman first makes sure the ferry is fastened securely to the bank and the wing is down, making a ramp to drive on. He then motions the car onto the ferry and has the driver pull clear to the front. The weight of the car on the front raises the rear to help the ferryman pry away from the bank.

To leave the bank, the ferryman must unfasten the line to the bank. If there is a winch, he must loosen it and unhook the cable from the ring on shore. After doing this, he has to pry the ferry away from the bank with a pole and jump on. He then raises the wing.

Normally the quickest way between two points is a straight line, but if a ferryman tried to take an old-fashioned ferry across the river in a straight line, he would have trouble. He must take it across slantwise, like a side winder, for the current, going down river, not across, would take the ferry with it. Also to use the power of the current and to control his speed, the ferryman pointed the boat either upstream to cast off or downstream to land. Hence the sideways movement. Today, most ferries are mechanically powered so they usually can travel in a straight line since the motor has more power than the current.

The continuous cable going through the big pulley also goes through single pulleys located at each end of the ferry (photo 26e).

26e Ferry Pulley From the single pulleys the continuous cable wraps around a windlass located midway on the upstream side of the ferry (photo 26f).

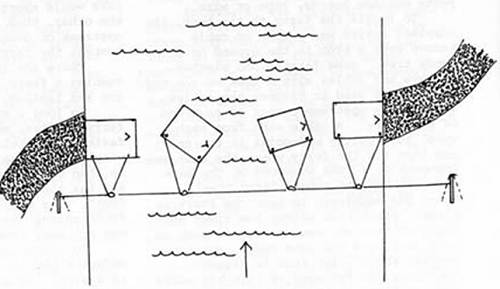

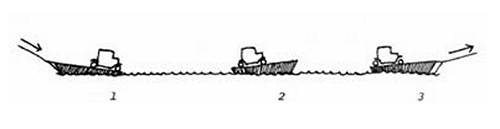

26f Windlass To use the power of the current to cross the river, the ferryman points the ferry upstream using the windlass, pulleys and continuous cable until over half way across. He then turns back downstream to land (photo 26g).

26g Diagram of Ferry Crossing The general principle of using the force of the current to cross the river is really quite simple. To cross the river, the ferryman turns the windlass, which in turn pulls the lines through the pulleys to point the ferry slightly upstream. Held by the big cable strung across the river so it can't go downstream with the current, the ferry is pushed across by the current. The force of the current, as it hits the oar board and goes over it and under the ferry, causes forward movement. When over halfway across the river, the ferryman turns the windlass to point the ferry toward the landing. Then, when the ferry is turned downstream to approach the landing, there is enough momentum left to glide gently into the bank. The lines and cable prevent overshooting the landing.

Once the ferry is out in the stream, the ferryman has the driver back his car to the rear of the ferry. The weight on the rear raises the front end slightly, making the approach to the landing easier (photo 26h).

26h Weight Balancing using Automobiles

1. Pulling to front of ferry raises back when leaving bank.

2. Midstream, driver backs car to back so...

3. Its weight raises front for unloading.

Many times drivers would be afraid to back their cars for fear of backing off. The ferryman would then do it for them. Some incidents did happen when the driver backed too far so that the rear wheels went off the ferry. Though it was frightening, there was usually no harm. Some men would push the car back on to the ferry when the ferry reached the other bank.

If, for any reason, the ferry should stop in midstream, the ferryman gets his ferry pole, a dried pole approximately fifteen feet long, three inches in diameter, and manually pushes the ferry the rest of the way across the river to the landing.

There was sometimes slight difficulties in controlling the speed of the ferry. The only way the ferryman could slow it down any was to turn it more upstream so that less water hit the oar board and the side of the boat. This position would allow the current to move straight through without exerting force against the oar board. If the ferry was straighter (at right angles to the current), the force of more water against the side of the boat would cause a tauter cable, forcing the big triangular pulley to move on the big cable at greater speed. Sometimes, if the speed of the ferry wasn't controlled properly, the ferry would hit the bank too hard.

Held in place by cables and pointed upstream, the ferry is pushed across the river by the force of the current going over and under the underwater oar board. The large arrow indicates river current direction (photo 26i).

26j Diagram showing how River Current pushes Ferry After coming in contact with the bank, the ferryman must lower the wing, jump off and fasten the ferry securely to the bank. The car may then drive off the ramp and go on its way.

There were many hazards involved with the operation of a ferry, but the most costly to the ferryman were sinking, ice and flooding, as these did the most damage to his ferry.

The ferry would not sink often, since the ferryman was always alert to avoid water in the hull. Even though builders used tar or pitch to seal the cracks, a ferry still leaked some. During a twenty-four hour period, it might leak an inch or two over the whole ferry. Water also got in the hull from rainfall leaking down through the floor. So, using the trap doors in the floor to get into the hull, he had to bail water out every day to avoid water buildup.

Occasionally a ferry would sink during a flood, or sometimes a rock would punch a hole without anyone knowing it, so that during the night enough water might build up to sink it. If anything like that did happen, to recover it, the ferryman had to use pumps that would pump the water out of the ferry faster than it was running in.

Ice was another danger. The problem wasn't the ice in the river, but the added weight of ice frozen on the ferry, for if enough ice got on the ferry, the weight could possibly sink it. When ice accumulated on top, the only solution was to chop it off with a pole or break it off any way possible. Very rarely would the river freeze entirely over. The current was usually strong at the ferry crossing, and most of the rivers were fed by spring water which normally kept the river temperatures above freezing.

Mr. Sutton said of the Current River, "I could remember ice coming down only two or three times in my lifetime. Big chunks of ice would float down the river, huge chunks, and in old times, way back in the 1800's, she'd freeze over. People drove across in wagons. Now I've seen that.

"The Current River is fed by springs all the way from Montauk to below Big Spring--and the spring water stays a minimum temperature of 58 degrees year round. Therefore, the river has a fluctuation of warm water and is rather hard to freeze over."

Flooding was probably the most common natural hazard, since Ozark rivers rise quickly during heavy rains, sometimes six inches an hour. Because of this, the ferryman had to constantly watch the water level.

When the river reached a certain stage above normal--two to five feet, depending on the particular river--the ferry had to be shut down. As the water was rising, to keep the ferry out of the current, the ferryman had to keep pulling the ferry up in the road, and as the water receded, he had to gradually lower the ferry back into the river. Failure to keep the ferry pulled up might result in its being washed downstream, and failure to lower the ferry back into the falling river might result in its being stranded until the next high water.

Another flood damage resulted from trees and logs being swept downstream. Should one of these hit the ferry, the force could be enough to sink it, or snap the main cable or lines, washing the ferry downstream. During flooding times the ferryman stayed up all night to keep watch on conditions. If possible, he might pull the ferry to a cove away from the current until the river subsided.

Flooding danger could happen anytime of the year, but was most frequent in the spring. Depending on the size of the rivers, most would crest and fall within a twenty-four hour period after heavy rain. When the water receded, the ferryman had to repair the washed-out landing, fix the approaches by hauling in clay and other materials, remove any debris left in the way, as well as inspect the ferry and make any other necessary repairs, such as broken railings, repair any new leaks and, of course, scoop out water.

Even without flooding, water levels fluctuated so that some ferry locations had special high water hookups for the ferry. Ferries with permanent concrete landing ramps on the bank made provision for higher and lower water levels.

In the opposite extreme, sometimes in summer or early fall there would not be enough water. This condition, though not as potentially dangerous as a flood, was of major concern because it caused the ferryman greater work. During a drought, rivers occasionally got so low that the ferryman had to scoop out the gravel from the landing approach to enable the ferry to get close enough to shore to unload the cars. Also, if the river became sluggish enough that the current wouldn't take the ferry across, the ferryman would have to pole the ferry to and fro across the river.

It is difficult for modern motorists to envision all the work and trouble it used to be just to cross a river they could easily throw a rock over. Used to speeding on high bridges over streams they hardly notice, most would be frustrated and impatient to have to stop, wait in turn and then one or two cars at a time, float at a snail's pace across a hundred foot river. But, on the other hand, some motorists drive miles out of the way just to experience riding a ferry. They consider it an adventure into the past to drive on to the rattling, unstable ferry and glide silently to the other bank.

To leave the bank Jim Purcell first loosens the winch to relieve the pressure on the line holding the ferry to the bank (photo 26j).

26j Loosening the Winch He next unfastens the ferry from the ring anchored on shore (photo 26k).

26k Releasing the Ferry from the Anchor After prying the ferry from the bank (photo 26l), he guides it across the river using the windlass (photo 26m).

26l Prying loose the Ferry from the Bank

26m Using the Windlass There are very few current-powered ferries left, except for places such as Akers in Ozark Scenic Riverways, where, for old times sake, a ferry still crosses the Current River. Either because there wasn't enough traffic to make them economically feasible on out-of-the way crossings, or because bridges were built to replace them on heavily traveled roads, one by one the ferries have disappeared.

If the ferry stops for any reason, the ferryman has no recourse but to pole it on across (photo 26n).

26n Pushing the Ferry with a Pole Jim gives Linda Lee a free ride across the river (photo 26o).

26o Riding the Ferry If handled correctly, the ferry will glide gently and squarely on to the landing (photo 26p).

26p Reaching the Other Side Copyright 1981 BITTERSWEET, INC.

Gloria and Jim Irwin were by the museum the other day to donate some class photos of School of the Osage classes from the 1950’s (photo 27).

27 Gloria and Jim Irwin Gloria is the daughter of Ray and Brooksie Behrens who have given much historical information to our museum library, especially in regard to Old Bagnell. Gloria is a graduate of School of the Osage and Jim is a graduate of Camdenton High School. He for more that thirty years was the voice of the Green Bay Packer Football Team. Also, for 22 years he announced the games of the University of Wisconsin football team and for 19 years announced the games of the Milwaukee Bucks and Brewers. Jim got his start with local radio station, KRMS.

A few years ago he and Gloria retired to live in California. They come back to Missouri regularly at this time to visit Gloria’s father, Ray, who is a resident of Heisinger’s in Jefferson City.

In between and behind Gloria and Jim is a portrait of the baby sister of Gloria’s mother, Brooksie, Gladys Ellen Bowlin, who died tragically at the age of 2 due to diphtheria in 1914. The significance of the portrait is the exquisite framing and the unusual quality of the photographic technique which in those days would have been very expensive to obtain (photo 28).

28 Gladys Bowlin Also donated was an old dress which was made for Gladys and appears to be the one she was wearing in the portrait (photo 29).

29 Dress for Gladys Ellen In addition, the Behrens' donated a friendship quilt given to Brooksie many years ago made by the Bagnell women as indicated by the names sewn into the quilt (photo 30).

30 Friendship Quilt by Bagnell Ladies Group

I had a nice conversation with Wallace Vernon, originator of the Vernon Publishing Company, the other day at our museum Grand Re-Opening. One of the things we discussed was the fact that one of our displays had answered a question he had wondered about for a long time. So it was a pleasure for me to read in this week’s Advertiser his comments about that mystery he and I had discussed:

MYSTERY SOLVED

GAY’S TAVERN originated as William Cahill’s Model Gas Station (photo 31), one of the first to operate at the 52-54 junction south of Eldon.

31 Gay's Service Station It became Gay’s Tavern in the early 30s and was demolished by Clarence Musser to build Musser’s Resort in 1936. Ex Pub (Wallace referring to himself) copied this information right off the wall during the grand re-opening of the Miller County

Historical Society Museum in Tuscumbia Saturday afternoon. Make no mistake about it, folks, the Museum people have done a magnificent job of displaying the county’s history in that renovated and expanded building. Make some time to take a tour. You’ll enjoy it!

That's all for this week.

Joe Pryor

|