|

Monday, April 27, 2009

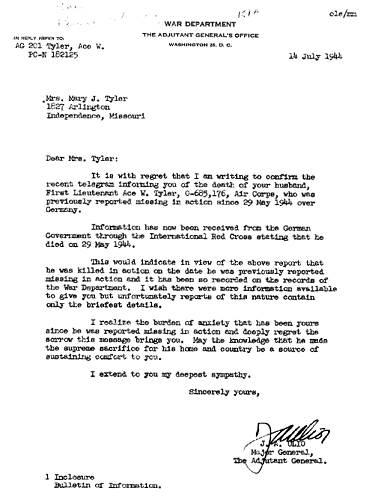

Progress Notes

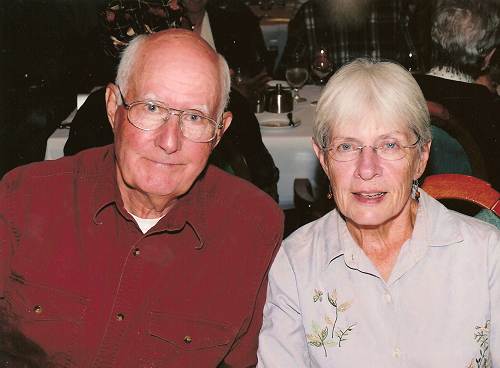

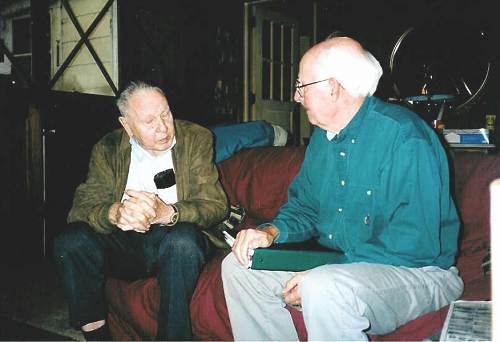

A month ago on March 23 I presented the Tylers’ of Miller County with an emphasis on the Barney Tyler family (photo 01).

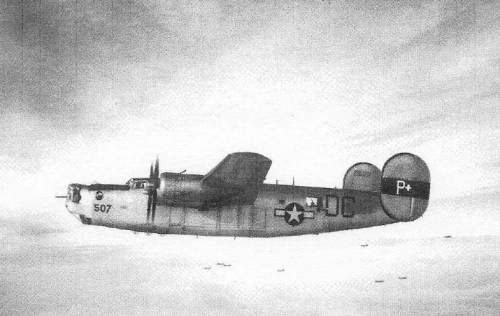

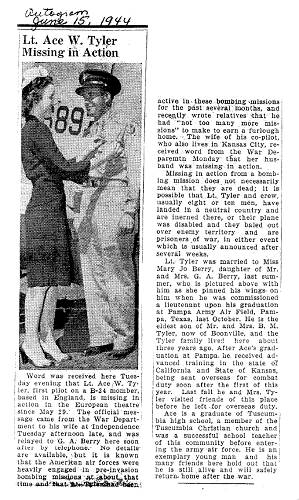

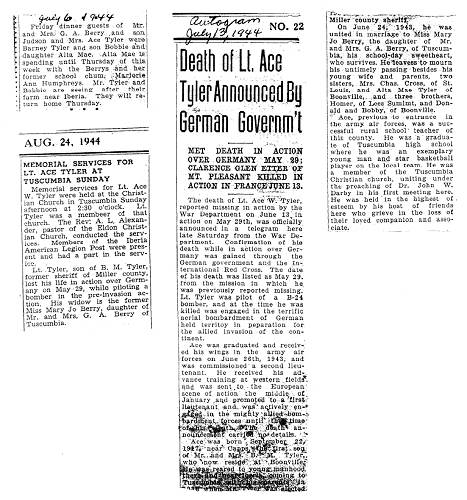

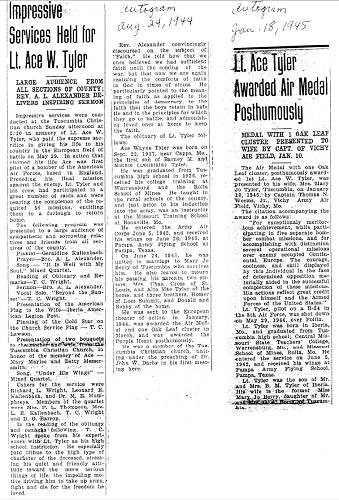

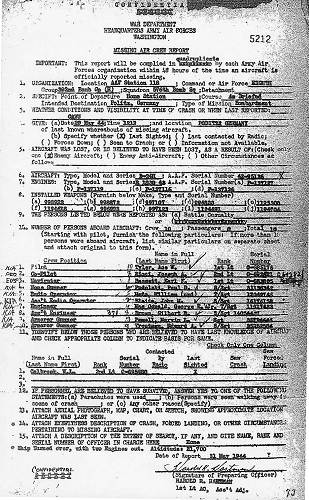

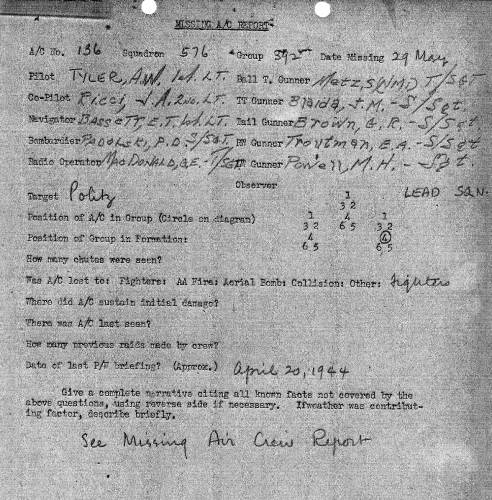

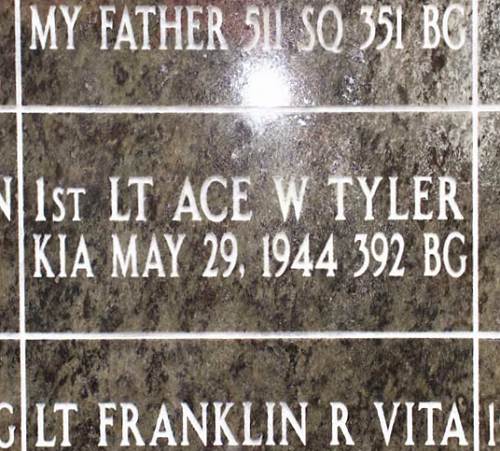

01 Barney and Minnie Tyler One of the stories included in that narrative was about the tragic heroic death of Barney’s son, Ace Tyler, Army Air Force pilot, who was shot down over Germany in 1943. Ace’s brother, Bob Tyler, just a few years ago completed a very well researched accounting of that event from which he composed a very interesting and gripping narrative (photo 02).

02 Bob and Alice Tyler Bob had told me a couple of years ago he was in the process of compiling the data from his research after which he planned to author the story for the purpose of informing relatives and friends of just what it was like to have been a World War II pilot facing intense enemy fire while trying to complete a bombing mission. Bob gathered data from files obtained from the Department of Defense which up until recently had been closed to the public. He also made a trip to Germany to visit the exact site of the crash of Ace’s B-24 bomber and to talk with individuals still living who witnessed the plane come down in flames.

Recently, Bob sent me a copy of his story about Ace. It is fairly long but I found it so interesting I read it all at one sitting. Bob also included quite a few informative photos including shots of the airplanes used during the air war in Europe as well as interesting detail on how they were constructed. I thought this week I would put the entire narrative on our website rather than serialize it because I think it is more interesting and meaningful to read at one time in its entirety.

The story is a wonderful tribute to the heroic efforts of Ace and his fellow pilots. I was greatly impressed by the brave sacrifice of so many American soldiers and airmen who were fighting so bravely to the point of death to save Europe from its own destruction. How this story of sacrifice and unselfishness contrasts with the image Europeans want to portray we Americans today; how soon they forget!

I believe many of you will find the narrative very informative and more than that, reinforces the belief that many of the most courageous, heroic and capable young men our country ever produced were lost in this selfless effort to save Europe from the despotism of Nazism.

ACE’S STORY

Robert W. Tyler

2009

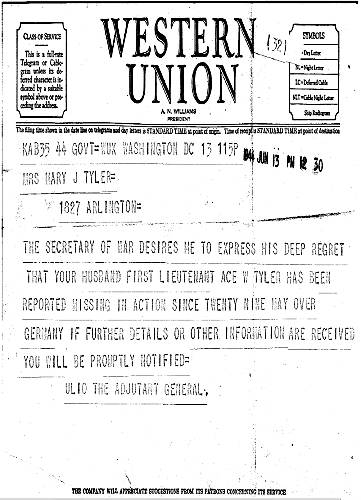

FOREWARD

When I was an early teenager in 1944, my oldest brother, Ace, was a hero to me. Now, almost sixty-five years later, and after doing the research for this story, he has become even more a hero. Through the years, I and my family often were curious about Ace’s war experiences. We had only a small amount of knowledge about his last mission and how he died. This was that he and eight others of his crew of ten were killed on a mission to Politz on May 29, 1944. One crew member, the navigator, had parachuted to safety and taken a prisoner. The lack of information was largely due to censorship of communications. Obviously, many questions were raised in my mind about this difficult time in the family history. So after I retired, I began to try to find some answers. A few years earlier, information in the National Archives about the military had become declassified and available to the public. Unfortunately, many military personnel records housed in St. Louis, Missouri were destroyed in a fire in the early 1970s. These included records of Ace. The information gathered for this story which follows comes mainly from two sources. One valuable source was the many letters written from Ace to other family members, largely to Homer, his brother, and to Mary Jo, his wife. Of course very little, if any, secretive information could be included in the letters. After his training and when he became a pilot with a crew, Ace was responsible for reading and censoring letters of other crew members. Obviously, he was very careful not to include anything sensitive in his own letters. The other major source was the military records housed in the National Archives and other Government Agencies.

The organization of the story is divided into a chronological order of events. After some family background information is given, the different phases of air cadet training are covered. Then the period of preparation for combat is followed by the actual combat missions which occurred in the Spring of 1944. The time after the word of his Missing in Action is obviously a time of hope, and when the confirmation of his death arrives, it becomes a time of mourning and reaching out to others in the crew families. Other parts include: information gathered in the search for family members of the crew; details about our visit to Wendling Air Base in England; and the trip to the site of the fatal crash in Germany.

Several acknowledgements need to be made in regard to completing this work. First, to Ace’s wife, Mary Jo. She talked with me and encouraged me in my work and provided me with many letters, pictures, and other materials which were very important. Then after her death in 2002, her brother, Jud turned over to me her saved documents, pictures, etc. Homer had also saved many letters that he had received from Ace. After Homer’s death in 1994, his wife Lou had given boxes of these letters to Alta and she gave them to me. These were very important in following the training phases of Ace’s military career.

I would also like to acknowledge the assistance given to me in my research at the National Archives. Ben Jones, a researcher for the B24.net web site really got me started in the research at the Archives. (The B24.net web site is dedicated to the 392nd Bomb Group and is a rich source of information). Ben grew up near the Wendling Air Base in England and was always interested in the history of the 392nd Bomb Group. Another researcher of the web site, Annette Tison, has been very helpful in pointing out sources and making suggestions. Many hours have been spent in talking with her about the 392nd. Her uncle was killed in the April 29, 1944 mission to Berlin.

Many others have given me valuable assistance in my endeavors. Jim Marstellar and Carsten Kohlmann were very helpful in organizing the trip to Germany. Jim is active in the 392nd memorial group and was instrumental in getting me in touch with Carsten. Carsten is a military historian in Germany and helped locate a contact who lives and works in Burow, which is close to the crash site of Gueltz. This contact was Ilona Hausler. She served as our guide and translator during our visit to the crash site in 2003.

I would also like to give thanks to Don, my brother, and Alta, my sister, who gave me encouragement and motivation to continue this project. Ronnie Cross, my nephew, was also important to me in the development of this story. He looked at my information and read earlier versions, giving me valuable suggestions. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my wife Alice and her encouragement. She also was my partner in the ventures to places in Europe and this country to learn more about the details in this story. She shared and understood my tears as I relived the memories.

When I read the many letters of Ace’s, it became obvious to me that early in his training he developed a real love for flying. He wrote of the feeling of putting the plane through the many maneuvers they had to learn and how exhilarating it was for him. I have chosen to insert here a poem which possibly became the most famous to come out of World War II. I think it reflects many of the feelings a flyer has. It was written by a young American flyer who had enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force and sent to England to fly for them in the early days of the war with Germany. His name was John Gillespie Magee and he flew a Spitfire on a test flight where he flew as high as 30,000 feet. When he landed he wrote to his parents in America and said, “Am enclosing a verse I wrote the other day. It started at 30,000 feet, and was finished soon after I landed.” On the back of the letter he had scribbled what was to become the most famous aviation poem of the war: “High Flight.”

|

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds-and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of-wheeled and soared and swung

Hung in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air.

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark, or even eagle flew-

And, while with silent lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

|

A few months after this, Magee was killed in a midair collision on a training mission not far from where he had written his poem.

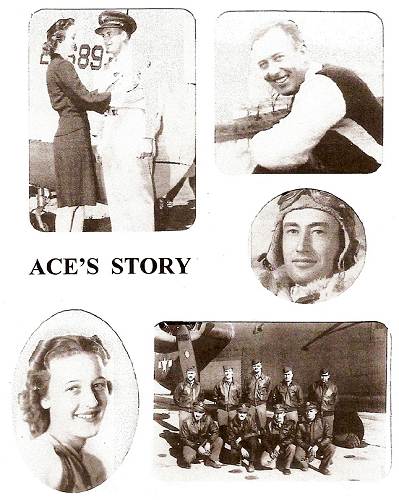

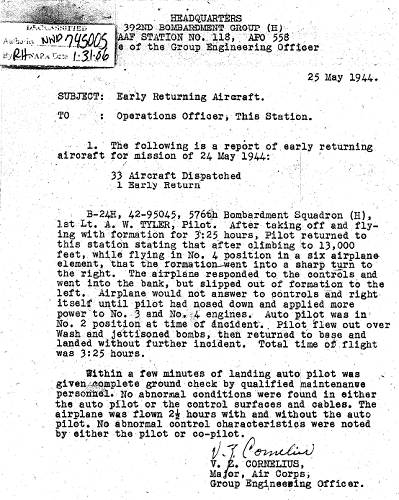

03 Ace's Story INTRODUCTION

This is mainly a story of the military life of Ace W. Tyler. Some background information will be given in order to better understand the person that he was and how his life evolved. Information is based on family records, letters to family, and military records obtained through various sources. An effort has been made to make the sequence of events as accurate as possible, although tight censorship of information after Ace went overseas left some gaps in completely exact dates. This story is an attempt to make available to future readers the details of the life and experiences of Ace. As his youngest brother, the writer of this story is hopeful that those who read it will learn and remember a little more about how Ace lived and died.

Robert W. Tyler, author.

THE EARLY YEARS

Ace Wayne Tyler was born on September 22, 1917 on a farm near Capps in Miller County, Mo. His parents were Barney M. Tyler and Minnie Grace Tyler and at the time of his birth, he had one older sister, Norma Evelyn, who was born in 1914. Younger siblings of Ace and years of birth were Otis Floyd, who died as an infant in 1920; Homer Clay, 1922; Donald Eugene, 1926; Robert William, 1930; and Alta Mae, 1934.

Many have wondered where the unusual name of “Ace” came from. It was a name taken from “Uncle” Asa Grady, a half-brother of our Great Grandmother, Mary Susan Tyler. Most everyone pronounced our brother’s name as the “ace” in a deck of cards. Our parent’s most often used the pronunciation like “A-C”.

Our family lived on a farm most of the time when the children were growing up. My mother used to say that “Dad” was not happy in one place too long. Another reason was likely that, given the state of the economy, one had to move where the best chance to make a living could occur. Consequently, there were quite a few moves when the children were small. From the time when the first child was born (Norma) until the last one was an adult (Alta), there were about fifteen different moves. These included several places in Miller County, two in Maries County, Boone County and Kansas City, Mo. Our father was a farmer and a carpenter and as his sons got old enough they took on chores on the farm, and the daughters did the usual jobs girls did in those days in addition to some farm chores along with the boys.

In the late 1920’s the family moved from Kansas City to the Lurton Farm (photo 04) which was about seven miles down the Osage River from Tuscumbia, Mo.

04 Lurton Farm House - Circa 1932 This was a large, river bottom farm and kept everyone very busy to try to scrape out a living during this poor period. Ace and Homer (Don and Bob in later years) attended the one-room school of Lurton which was about a two-mile walk from the home. Ace and Homer then attended the high school in Tuscumbia.

In 1932, our father decided to enter politics and ran for the Sheriff’s office in Miller County as a Republican. He lost this election in the Democratic domination of most national, state and local offices. He ran again in 1936 and won the election. Therefore, a move to Tuscumbia, the county seat followed. The year before this move, however, Homer developed polio and was in the hospital in Marshall, Mo. for several months. One leg was permanently crippled and he wore a brace and walked with crutches for the rest of his life. In Tuscumbia, we lived in an apartment above the jail house next to the court house. Ace graduated from high school in 1936, Homer was in high school and Don and I were in elementary school. Ace’s graduation class had a total of eighteen students. After attending college at Iberia Junior College he took the teacher’s exam. And his first teaching job was in the one-room school at Capps. Later in 1940-41 he taught at Skinner school which was near Eldon. Ace attended college in Warrensburg and Rolla School of Mines in summers for teacher training courses. While in high school Ace played on the basketball team and continued to play for a “town team” after high school (photo 05).

05 Tuscumbia H.S. Basketball Team - Circa 1935-36

FR: Homer Clay Wright - Coach, Gene Templeton, Bill Hall and Alva Vaughn

BR: David Bear, Otis Nixdorf, Joe Wickham and Ace Tyler He evidently was a good player, scoring 8-12 points each game. This was a good part of the team’s total, since during that time very seldom was there a score more than about 30.

Ace and Homer both developed a love for the outdoors and fishing and hunting were always an important part of their lives. Ace got a young bird dog in 1940 and named the dog Wilkie after the Republican presidential candidate of that year. When Wilkie lost to Roosevelt in the election, however, he renamed the dog Lad.

Across the street from our apartment in Tuscumbia lived the Berry’s. Garrett and Clarice Berry had four children who were close in age to the middle four in our family. Mary Jo was the oldest, followed by Wendorf, Conley and Judson. Naturally, the children spent a lot of time together. Ace and Mary Jo began dating around 1940 and would later marry (photo 06).

06 Wendorf Berry, Mary Jo Berry, Ace and Homer - 1939 On completion of the four-year term of office, our family moved to Iberia, Mo. In Dec., 1940. We lived in what was known as the Adam’s house which was, ironically, next to the place where my Doubikin grandparents lived when my parents married in 1911. In late 1941, Ace took a job in Boonville, Mo. with the Missouri Training School for Boys, Norma was working in St. Louis, and Homer would start to school at the University of Mo. the following Fall (1942). Don, Bob and Alta were in the Iberia schools. Of course, the memory remains of the event of Dec.7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor and the beginning of World War II for the U.S. Our father went to work as a carpenter to help build barracks buildings at Ft. Leonard Wood and we had at least two boarders who lived with us and worked at the “Fort”. During the summer of 1941, Ace had worked in Kansas in the harvest and had been classified 1-B by the local Selective Service Board.

Even at this time, his goal was to get into the Air Force. One of his physical examinations showed evidence of sugar in the blood and this was a factor that delayed his plans. A later examination cleared him however, and he entered the service on June 5, 1942.

MILITARY TRAINING

Ace was sent to the reception center at Jefferson Barracks, Mo. He had applied for Aviation Cadet Training in April, 1942, before entering service, and was accepted for this training officially in August, 1942. He was told on June 6 that he had qualified for Flying Officer’s Training School and Radio School, which was his second choice. His basic training occurred at Jefferson Barracks and then he was assigned to Air Cadet Training in San Antonio, Texas. In the late summer of 1942, the family moved to Boonville, Mo., where Dad worked in the carpenter shop of the Mo. Training School for Boys. We lived about 2-3 miles outside of town on the poultry farm of the Training School. Mom took care of the chickens (thousands of them), egg gathering, etc. with a little help from Don, Bob, and Alta, but mostly help from a couple boys from the Training School.

PRE-FLIGHT TRAINING

Pre-flight school in San Antonio, Texas began Oct. 11, 1942. It was scheduled to continue for 7 - 9 weeks. In a letter to his brother, Homer in November, 1942, he told about his being named a “Flight Lieutenant” and was given a private room and more responsibility. At this time he mentioned that he wished he had taken more mathematics in school and said,

“…dropped my pencil the other day (in class) and before I could pick it up I’d lost out on a half-year of college physics.”

In this same letter, he said,

“The boys have begun to drop out one by one and the rough stretch is yet to come. I’m keeping my fingers crossed.”

During this period Ace indicated that he and Mary Jo were going to get married and he hoped that he would be able to get leave over Christmas (1942) when they may be married. The leave did not occur and the marriage plans were delayed.

PRIMARY TRAINING

With a transfer to Chickasha, Oklahoma on Dec. 13, 1942, the actual flying part of training began. Primarily they were flying in Fairchild Primary Trainers (P.T. 19A’s). Ace had written to Homer describing it as having “an inverted 6-cylinder Ranger engine with cruising speed of around 100-115 mph. (They’re red-lined at 220 per.)” (photo 07)

07 Ace with P.T. 19A flown in Primary Training It seemed that Ace enjoyed the thrill of flying as evidenced by what he wrote to Homer on Jan. 2, 1943:

“If you really want to get a thrill try going up around 4000 ft. and push the nose up to the blue until the ship begins to shake like a man with a chill, and dropping off on one wing into a spin and go down turning round and round then kicking the opposite rudder, slamming the stick forward and easing it back. After the first spin everything is just as clear as crystal and you don’t try to hide in the cockpit. We flew upside down awhile the other day and that’s quite a feeling too. These ships are really sweet crates. They’re washing them out pretty fast and one can’t tell when he’s getting a check ride, but it’s certainly no disgrace to washout at this stage. One guy got the skids that had over 1000 hours of flying time with a transport company.”

An important event in a pilot’s life occurred for Ace on Jan. 5, 1943. He wrote to Homer,

“I know you’ll be surprised - but I SOLOED today! Ha! We were practicing landings and the instructor climbs out and slaps me on the shoulder and says, ‘Now take her up and show a few good landings and we’ll go home.’ Man, alive! I swallowed a couple of times - gave her the gun and got in 18 minutes of solo time! It’s a great sensation and that ship responds like a baby. I’ll tell you sometime just how I felt. Ha. Am really proud of those solo wings. Let’s hope I can stay on the ball team, eh!”

A letter of Jan. 9 was further indication of Ace’s love of flying and his continuing good humor:

“All the farmers around here stay inside and their cows have quit giving milk since we’ve begun to solo. Ha! It’s really a rat race up there now. A couple of fellows were flying solo over on an auxiliary field yesterday and upon landing one fellow got too close to the other and his prop chewed the first plane’s tail assembly all to pieces. Ha. We let down right after it happened and the instructor crawled out, looked at me and said, Nervous?’ I wasn’t so he told me to take her on up. Am improving in my landings and don’t bounce 20 or 30 ft. every time I hit the ground. Ha. We were up around a mile high today doing stalls and spins. You can see for miles and miles and looks as if there’s a patchwork quilt spread out beneath you. Am getting so I can do a fairly decent spin now. It’s a little scary starting the spin, but while you’re spinning everything is just as clear as crystal. We’ve done stalls, spins, S’s, elementary eights, rectangular courses, climbing turns, gliding turns, Schandells, landings, take-offs, and a few more simple maneuvers. Ha. I’ve done all of them by myself but they’re pretty rugged yet. Ha.”

A letter to Homer on Jan. 30 further indicates the joy of flying, but also the difficulty of training and anxiety about being able to complete this phase. He wrote:

“Well, Homer, your ol’ bud has only about 12 or 13 hrs. to go (flying time) here. They’ve been washing out an awfully lot lately. I guess we have around 85 left out of our original 200+. Two of my buddies washed out - one today and the other a couple days ago (VanFleet and “Goldie” Thompson). I’m due for my check any time now and I dread it. Have been doing everything in the book. We’re allowed 2 ½ hrs of flying time each day. Of course we’re only on the line ½ day. The hardest maneuver for me is a half-roll or maybe the Immelman. It’s a little difficult for me to manipulate the controls when I’m wrong-side up. Ha. Usually get around two hrs. solo each day and believe you me if it’s at all rough one gets plenty worn out. Hope I can stay on the ball team. Am getting so I don’t give a d… though.” . . . “A fellow got lost yesterday and they found him about 18 miles or so out of the area down in a stubble field without a scratch. Our practice area is about 15 by 20 miles. Lots of room to play around but the planes are as thick as flies.”

Mary Jo came to visit Ace on the weekend of Feb. 13-14 and he left Chickasha for Enid, Oklahoma for Basic Training on Feb. 16. He indicated that they would be flying B.T 14’s, with a 450 H.P. engine. They were supposed to get quite a lot of formation and night flying. He told Homer:

“Say, kid, I’d give anything to get you “upstairs” in one of these P.T.’s, ha. Two-bits to a nickel I could make you ’toss your cookies’, ha.”

BASIC TRAINING

There were quite a few cross-country trips of about 200 miles and night flying included in Basic Training. This was also where Ace had his first exposure to tight formation flying. Evidently security became more strict as Ace sent his camera to Homer and said that he was not allowed to use it.

Several times, Ace indicated how hard they were working and how tiring it was for him. He also appeared frustrated at times about the supposedly strict discipline rules they had to adhere to, even though he realized that there were a lot of very young guys in the program and it probably was needed.

According to his flight records, Ace logged 73 hours of solo and another 67 hours of dual flying while at Enid. Near the end of Basic Training, Ace was hoping for a pass so he could go to Kansas City to see Mary Jo. He did get a short pass in mid- April and spent the weekend in K.C. He said there was not enough time to get married then, but they were planning it at the time of his graduation from Advanced Training. He was transferred to Pampa, Texas on April 19, 1943 for Advanced Training and would receive a commission upon graduation.

ADVANCED TRAINING

Most of the training at this station would be in A.T. 17’s which were twin engine planes (photo 08).

08 A.T. 17 Flown in Advanced Training It was indicated that they always flew with at least two people in this plane, although it had a capacity for five. There were increased distances for cross-country flights (400-500 miles).

“Don’t know how I’m ever going to be able to fly for a whole day when 4-5 hours now just about peters me out. It really gets tiresome after the first couple of hours. The darn plane just flies like driving a car. We flew about 300 miles at 500 feet off the ground.”

During this stage of training, Ace also flew A.T. 9’s at times. He said the A.T. 17 was easier to land because it wasn’t as fast as the A.T. 9. He told about taking part in an air search for a lost plane from Lubbock Field. They were to fly slow (@120 mph) and about 500 ft. above the ground. He never mentioned whether or not the plane was found. Ace flew more and more formation and instrument flying. He spoke of this:

“Flew about an hour and a half under the hood yesterday. Man, I sure do hate that. A black cover is snapped over your seat in the cabin and you fly by instruments alone. I had a sad time following the beam in as I was a while locating myself. Ha. It’s possible to take-off, fly, and land these planes on instruments alone, but believe you me it’s certainly no child’s play.”

It was first in this letter of May 21 that he indicated what was expected for his assignment after graduation. He thought there was a possibility of getting a B-24, B-26, Air Transport Command, Air Service Command, or Instructor.

“The Ferry Command would really be a good deal, but chances of getting that are pretty slim.”

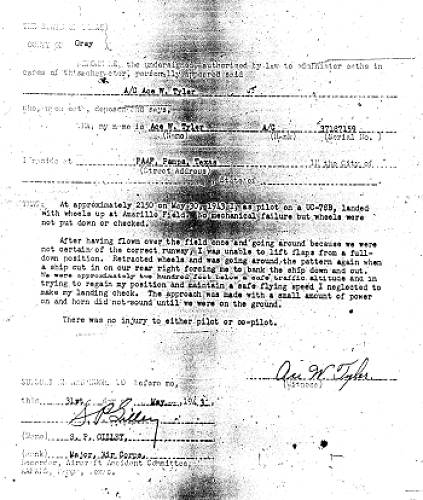

I discovered in February, 2009 that Ace was involved in a training accident during this period. On May 30, 1943, he had an accident which is outlined below in part of the accident report (photo 09).

09 Accident Report - 1943

Click image for larger viewHe never wrote anything about the accident and we were not aware of it. Fortunately, no one was injured and evidently, it was not enough to “wash him out”.

In a letter of June 11, Ace said,

“They’re flying us to a frazzle every pretty night and I sure wish this night time was all in. I still have better than eight hours of night cross-country time to get in.. . .I think Jo is coming down next week - I hope. Don’t know if I’ll get a leave or not yet. Would sure like to have a couple weeks.”

Ace finished Advanced Training and received his Silver Wings and was commissioned a 2nd Lt on June 24, 1943, and was married on this day to Mary Jo Berry (photo 10).

10 Pinning on his Wings - 1943 A brief leave followed in which they visited the Berrys in Independence, Mo. And the Tylers in Boonville, Mo (photo 11).

11 Tyler Family in Booneville, MO - June 28, 1943

(Last picture with family together) Ace was transferred to Liberal, Kansas on June 26, 1943 where he had his first contact with the B-24. He and Jo had a difficult time finding a place to live in Liberal, but finally found a two-bedroom place with a kitchenette. They shared this place with another pilot and his wife (Lt. and Mrs. Carl Yandt).

INTRODUCTION TO B-24

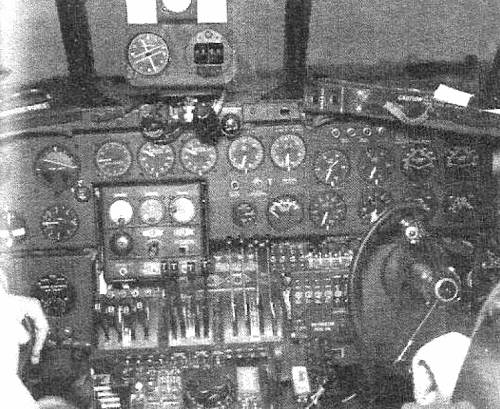

“The plane, lad, is really OK. The first time I looked at the instrument panel (photo 12), I almost fell backwards. Ha. Ye gods, and little fishes! You never saw so many instruments in your life. It just uses about 200 gallons of gas an hour (more than an “A” card for a year). All these planes are brand new, as is everything else around here.”

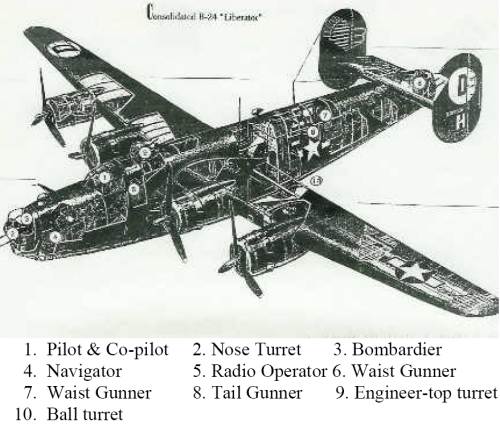

12 B-24 Cockpit Instrument Panel The B-24 was built in greater quantity than any other plane in World War II (more than 19,000). There were several different versions designated by different letters, changing with each modification made of the original. The name of “Liberator” was given the B-24 by the British early in its history. It was called by many other names, often in a derogatory way. Probably the most common was the “Flying Box Car”. Supposedly given the name by those partial to the B-17, saying that it looked like the “box” that the B-17 was shipped in. The Liberator had a wingspan of 110 feet, a fuselage sixty-seven feet long and eighteen feet high. Empty, the plane weighed 32,500 pounds. Its maximum weight with bomb load was about 60,000 pounds. The B-24H (most common version flown at this time) carried ten .50 caliber machine guns, two in the nose, two in the top turret, two in the ball turret, and two in the tail, all power-operated, and one manually controlled .50 caliber on each side of the waist. The plane had a maximum speed of almost 300 miles per hour, could fly as high as 28000 feet, and had a range of 3700 miles (without bombs), and 2100 miles with 5,000 lbs. bomb load, all exceeding the capability of the B-17.

It was almost universally agreed that the B-24 was the hardest plane to fly. George McGovern was quoted in Steven Ambrose’s book “The Wild Blue” as saying,

“I don’t think there’s a person alive that could fly a formation of B-24s for ten, twelve, thirteen hours that wasn’t trained the way we were. I don’t think he could do it.”

It sounded as if McGovern was impressed with the cockpit of the B-24 the way Ace was, saying that when he first climbed onto the flight deck and sat at the pilot’s seat, he was confronted by a bewildering sight. There were twenty-seven gauges on the panel, twelve levers for the throttle, turbocharger, and fuel mixture, four on the pilot’s side on his right, four on the co-pilot’s side on his left. The wheel, or “yoke” as it was called, was as big as that on a large truck. There were over a dozen switches, plus brake pedals, rudders, and more.

Note: I had an interesting conversation with a pilot of a B-17 in Feb. 2004 at the 8th Air Force Museum in Savannah, Ga. about comparing the B-17 and B-24 in regard to difficulty in flying. He told me that he had been trained totally on the B-24 and when assigned to his final station in England, he was told he would be flying a B-17. After four takeoffs and landings, he said they told him he was ready for combat. This indicates that if one could fly the B-24, they could fly just about anything. This pilot was shot down twice.

Jo would often write Homer, and include the letter with one from Ace. In a couple letters, she referred to Ace as “Cake-eater”. I’m not sure where this “nick-name” came from, but it sounds like one could figure it out. On their one-month anniversary, she said,

“Can you beat this? We were married just one month ago today and “my old man” says it doesn’t seem a bit over a year. Grounds for divorce, don’t you think?”

Ace said that he planned to fly over the folk’s house in Boonville on one of his cross-country trips. He wrote and told us when he would fly over and we anxiously awaited that day. Everyone rushed outside, waving and yelling. Of course, Don and I had been out there most of the day, waiting. It was an exciting time for us.

During his time at Liberal, Ace flew the B-24E, logging 56 hours in July and 75 hours in August and September (until the 9th) (photo 13).

13 B-24 of 392nd Bomb Group, 577th Squadron There was a lot of cross-country and night flying included. In one 24 hour period he spent 10 hours in the air. He indicated that each time he took the ship up he liked it better.

CLOVIS, NEW MEXICO

Ace was transferred to Clovis on Sept. 9, and Jo went back to Independence, since there was no place for them to live in Clovis. Information is sparse about the kind of training that occurred at this station. His flight records indicate that he flew in the B-24-D most of the time and logged 35 hours in about 15 days of flying while at Clovis. On Oct. 16, 1943 he was transferred to Blythe, California. Before reporting to Blythe, he was given a short leave so he went to Kansas City for a few days. He left there for Blythe on Oct. 22.

BLYTHE, CALIFORNIA

On reporting to this base, Ace found that his cousin, Raymond Gardner, was stationed there, so they had some good visits together. His air crew was organized at the beginning of the time at this station. He said,

“Have a swell crew. Navigator, Bombardier, Co-pilot and I went to the show tonight. A great bunch of guys. Rode with the co-pilot and he’s going to be OK.”

Again, Jo was not able to join him at this base since there was no place to live.

Ace did a lot of flying while at Blythe, mostly long distances, logging 66 hours in 18 days flying for the month of November. On five other days, time was spent on the Link Trainer. So they were quite busy during this time. He wrote on Nov. 24,

“Been flying our tails off lately on 8 hr. missions. I took some Major to El Paso, Texas last Tuesday. Took a Captain to Tucson and back here without stopping. We were up for 7 ½ hours yesterday and 5 ½ hours of that was at 20,000 feet on oxygen. Didn’t feel so bad, though.”

Following is a list of the crew members during the time in Blythe (photo 14):

2nd Lt. Ace W. Tyler Pilot - Boonville, Mo.

2nd Lt. Joseph A. Ricci - Co-pilot - Georgetown, Colo.

2nd Lt. Raymond J. Carley - Navigator - Brooklyn, N.Y.

2nd Lt. Melford R. Butts - Bombardier - S. Hanover, Mass.

S Sgt. George E. McDonald - Engineer - Holyoke, Mass.

S Sgt. William Metz - Radioman - Teaneck, N.J.

Sgt. Gilbert R. Brown - Left Waist Gunner - El Paso, Texas

S Sgt. George Dikun - Right Waist Gunner

Sgt. John M. Blaida - Tail Gunner - Monroe, Mich.

Sgt. Paul D. Podolski - Ball Turret Gunner - Dedham, Mass.

14 Original Crew (probably taken in Blythe, California

FR: Lt. Melford Butts, Lt. RAymond Carley, Lt. Ace Tyler, Lt. Joseph Ricci

BR: unknown, Sgt. Paul Podolski, Sgt. John Blaida, unknown, Sgt. Gilbert Brown On Dec. 20, the crew was transferred to Herrington, Kansas. During January, 1944, records are incomplete, but it appears that Ace and crew left Herrington on Jan. 10th and flew to Morrison Field, West Palm Beach, Florida. Just before leaving Herrington, George Dikun, Right Waist Gunner, was replaced by Sgt. Corbett X. Miller, hometown of Rockwood, Pa. Records do not indicate the reason for this change.

FLIGHT TO ENGLAND

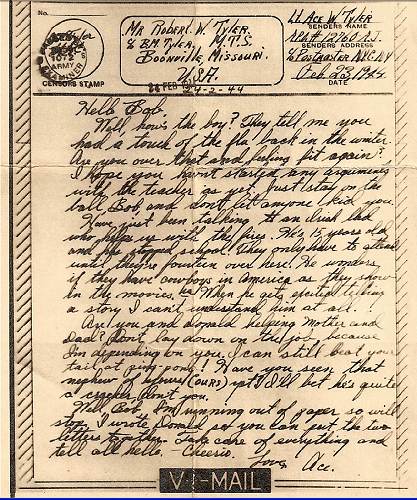

There were different ways the Air Force transported new crews to bases in Europe. Some were taken by ship from Eastern ports to Europe. Others flew planes a Northern route, going over Nova Scotia and Iceland, to Ireland and England. Many of them took a Southern Route which took them from Florida to some Island in the Caribbean, often Puerto Rico, then to Brazil, to Africa and then to the British Isles. Evidently this is the route Ace and his crew flew. The plane flown from the U.S. was No. 41-28712. I’m sure a short time was spent at each stop along the way, but the only record available of where they stopped was in Marrakech, in North Africa. They arrived there on Jan. 22. The next stop was in Ireland on Jan. 28 after over a nine-hour flight. They stayed at this station until Feb. 17, then transferred to Station #238, also in Ireland. This was the Combat Crew Replacement Center at Cluntoe, Northern Ireland (due west of Belfast on the western shore of Lough Neagh). This was where the newly-arrived crews reported, went through indoctrination, got last-minute training, and waited to be assigned to a Group. Below is a copy of a “V- Letter” written to me from Ace in Ireland dated Feb. 24, 1944 (photo 15).

15 Letter from Ace - 1944

Click image for larger view

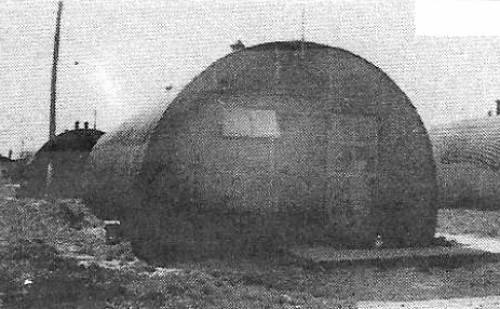

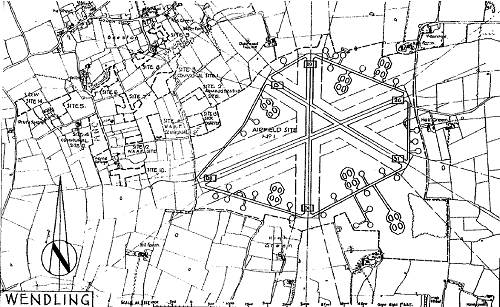

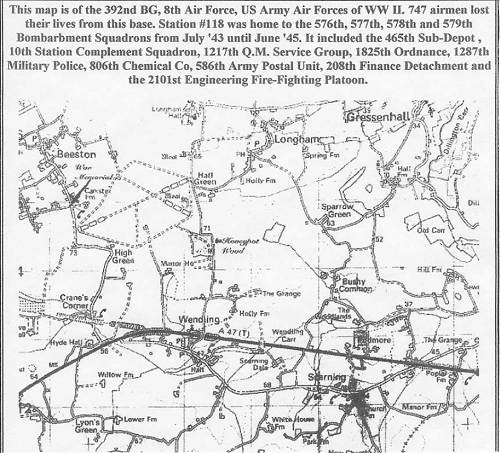

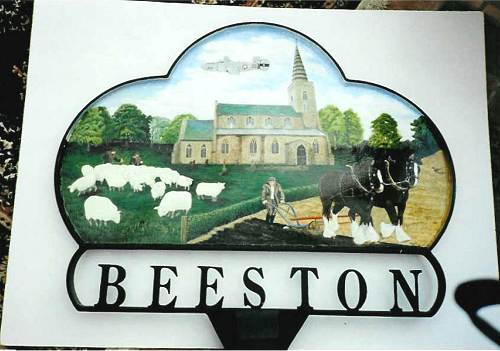

WENDLING AIR BASE

On March 3 the crew was assigned to the 576th Squadron of the 392nd Bomb Group at Station 118, Wendling, England. This base was actually closer to the village of Beeston, but the train stopped at Wendling, therefore they called it the Wendling Air Base. The following maps and pictures show the Air Base as it appeared in 1944. On the first map, Site #6 was where Ace’s squadron (576th) was housed (photos 16, 17, 18 and 19).

16 Officer's Mess with typical transportation in front

17 Quonset Huts where crews lived

18 Map of Air Field and Surrounding Support sites and Village of Beeston

Click image for larger view

19 Larger Map showing area including Villages of Beeston and Wendling

Click image for larger viewDuring the first week of March some time was spent on the Link Trainer and one flight of three hours was recorded. This was likely a training flight. The Quonset huts where the crews lived were heated by small stoves that burned coal. The normal means of transportation from one part of the base to another was by bicycle.

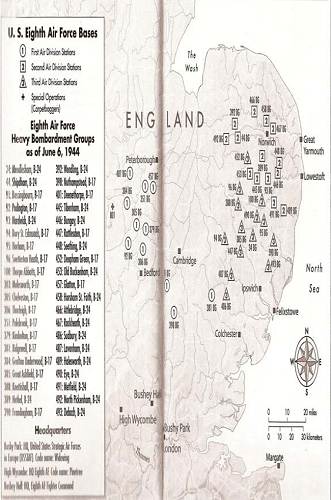

COMBAT MISSIONS

Before going into the details of combat missions of the 392nd Bomb Group in which Ace participated, and other significant missions, an attempt will be made to give some statistics related to the group and discuss the organization involved in carrying out the missions. The 392nd was only one of about 50 bomber groups flying from English bases in only the Eastern part of England, known as East Anglia. Many missions included several groups combined so that there may be a total of several hundred bombers on one mission. The following map (photo 20) shows how many bomber and fighter groups were part of the 8th Air Force and located in East Anglia. There were many others in other parts of England.

20 U.S. Eighth Air Force Bases

Click image for larger viewThe extremely crowded skies, combined with bad weather and poor visibility much of the time, made it very difficult. Many mid-air collisions resulted even before planes left the skies over England. After forming of the groups had been accomplished, planes were expected to fly in very tight formation-almost wing-tip to wing-tip. Another factor which contributed to formation problems was that the B-24 controls seemed to become even more sluggish than normal at altitudes above 20,000 feet. It took brute strength and extremely sharp reflexes to fly this plane. Pilots were expected to hold to this close formation, even when under attack from enemy planes, or through flak barrages, until bombs had been dropped. Even after this, their protection was best if they maintained tight formation for the trip home. So damaged planes often would not be able to stay up with the group and therefore, became prime targets for enemy fighter planes. Friendly fighter escorts were valuable, particularly for damaged planes. Early in the air war, Allied fighters did not have the range to accompany the bombers to many of the targets in Germany. Early in 1944, however, with the introduction of the P-51, escorts became more common on the longer missions.

Other factors that contributed to the difficulty of the missions included cramped space in the planes and temperatures at high altitudes. It was obvious the B-24 was not built for comfort and it was even difficult to get into the plane and out of it. The bombardier, navigator, and nose gunner squeezed through the nose wheel well of the ship, then found their place in the extremely small area in the nose of the plane. The nose gunner could not normally wear his parachute when in his combat station. The rest of the crew entered the plane through the open bomb-bay doors, walked along a narrow catwalk, then to either the cockpit or the waist and tail of the ship. Leaving the plane in an emergency was also difficult and many times they would have only a few seconds to get out if the plane had been hit (if they could squeeze through the small openings). The crew had to wear heavy clothing and electrically heated flight suits (which sometimes would not work properly or would short out when the electrical system was damaged). The temperature at high altitudes would be 30-40 degrees below zero, so the heavy, heated clothing was a necessity. The area of the waist guns on each side was completely open to the outside, allowing the wind and cold to blow through the plane. One can imagine the difficulty of moving around in the small spaces with all the clothing and equipment. Crew members also had to wear oxygen masks, since the planes were not pressurized. They would keep these on for hours at a time. The following picture shows the positions of the crew in the B-24 (photo 21).

21 B-24 Cutaway

Click image for larger viewWhen one looks at the losses of planes and personnel, the numbers are staggering. For the years of air combat in Europe, the U. S. lost almost 10,000 bombers of all types, plus another 8,000 that were damaged beyond repair. In 1944 alone, flak destroyed 3,501 American bombers, and German fighters destroyed about 2,900 more. The Eighth Air Force lost 26,000 airmen killed between 1942 and 1945. The 392nd Bomb Group, which was the fourth oldest in the Eighth Air Force, lost 184 aircraft and had 1,553 airmen casualties. Only the 44th Bomb Group lost more planes (192) than the 392nd. This may be partially explained by the fact that the 392nd was a leader in bombing accuracy. During the period of Feb.-May, 1944, it bombed with greater accuracy than any other European Theatre Liberator Group. They were dedicated and determined to achieve their goal of hitting the target.

Some other sobering statistics are that until mid-1944 the life expectancy of a bomber and crew was 15 missions, with a crew member having only 1 chance in 3 of surviving a tour (30 missions at this time). About 50% never made it through 5 missions.

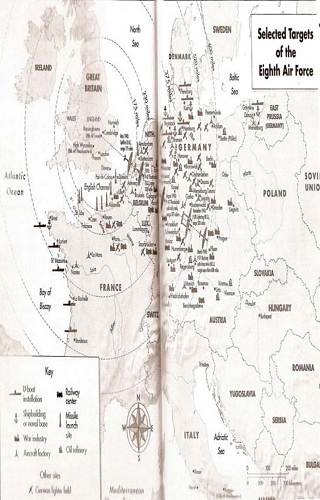

Targets of the 8th Air Force included U-boat installations, shipbuilding, aircraft factories, railway centers, missile launch sites, oil refineries, other war industrial plants, and others. The following map shows some of the sites bombed and the limit of the escort fighters for the missions (photo 22).

22 Targets of the Eighth Air Force

Click image for larger viewIn the following summaries of the missions, the ones for which Ace was given combat credit (counted as a sortie) are given numbers. Other missions may be discussed, since they were significant in the history of the group or to Ace’s experience.

Mar. 8, 1944: Mission #1

Target: Erkner, Germany

Erkner was about sixteen miles southeast of Berlin. The specific target was the ball bearings works. If the weather obscured the primary target of Erkner, the planes were to bomb the secondary target, which was the railway station in Berlin (Zoo-Garten Bahnhof). This was the first actual mission to Berlin, so they expected heavy resistance.

On a previous mission to hit Berlin, on Jan. 24, planes had been recalled due to weather.

Twenty-four planes of the 392nd participated in this Erkner mission. This was only a small part of the total force of bombers to this target that day. There were a total of 468 planes with three combat wings making up the lead force, four combat wings in the second force, and three combat wings of the 2nd Division making up the third force. The 392nd was in this third force. Escorts included seven P-47 groups, four P-51 groups and one P-38 group. The two leading wings were subjected to mass fighter attacks from Dummer Lake to the target area. Two P-47 groups heavily engaged the enemy fighters, and although greatly outnumbered, decisively outfought the enemy, claiming 30 destroyed while losing 5. A total of 63 destroyed, 17 probably destroyed, and 19 damaged were claimed by all fighter forces. For the total U. S. losses, it was 36 bombers lost and 40 received major damage while 17 fighters were missing while 9 sustained severe damage.

Ace was assigned as co-pilot in the Ellison crew. This was a normal procedure for a new pilot, and it was the 10th mission for the Ellison crew. The 392nd reports indicated that flak was encountered and some 25 single and twin-engine enemy planes were sighted. One of these was shot down. The bomb run was successful, with 1,184 - 100 pound bombs dropped. The Ellison crew flew in plane #560 and was positioned over the target in the right rear of the formation. Ace would fly this same plane in a later mission (Apr. 12 to Zwickau). (This plane crash landed at Wendling on 10/29/44 after 34 missions). Fighter support of P-51’s was reported as excellent. Fourteen aircraft of the twenty-four from the 392nd sustained some damage, but all returned safely with no losses or aircrew member casualties. They were fortunate to have been in the third force on this mission, since the greatest losses occurred in the lead force. The records indicated that a “highly jubilant group returned from this mission, our first real one to Berlin.” Ace’s flight records indicated that he flew 4:25 hours as co-pilot and 4:00 hours as first pilot. For the first combat mission, this must have been a memorable one. Below is a picture of planes dropping bombs on this mission (photo 23). One cannot identify aircraft numbers, but one of these may have been the Ellison crew’s plane.

23 Liberators dropping bombs over the Erkner Ball Bearing Factory near Berlin - March 8, 1944 Mar. 16, 1944: Mission #2

Target: Fredrichshafen

This was the first mission to this target of the Dornier Aircraft Assembly Plant on the north shore of Lake Constance in southern Germany. This was the first time Ace flew as the pilot. The following were crew members of this first mission as pilot:

Ace. W. Tyler, Pilot - W. Metz, Radioman

J. A. Ricci, Co-pilot - C. X. Miller, Right waist gunner

R. Mitchell, Navigator - G. R. Brown, Left waist gunner

H. E. Stetson, Bombardier - P. D. Podolski, Ball Turret gunner

G. E. McDonald, Engineer - J. M. Blaida, Tail gunner

Note that Ray Carley, Navigator, and Mel Butts, Bombardier of the original crew were not included. They both had volunteered to fly on an earlier mission on Mar. 6 to Genshagen with another crew and their plane was shot down, they parachuted out and were taken prisoner. Ace had lost his Navigator and Bombardier before even flying a mission with them. So on their first mission, they became POW’s and replacements (Mitchell and Stetson) joined the crew for this mission to Fredrichshafen. This information about Carley and Butts was obtained in Dec., 2003 through a telephone conversation with the widow of Mel Butts. He had died in the mid-1990’s. No information has been forthcoming about where Ray Carley is, or whether he is alive.

Briefing for this mission took place between 0345 and 0600 hours and at 0725 the first of 29 planes from the 392nd took off. Ace was flying in aircraft #670. On nearing the target, it was reported that there was 10/10ths cloud cover (totally obscuring the target). Mission reports indicated that the results of bombing were unobserved due to the cloud cover. No enemy aircraft were encountered and flak damage was minimal. Ace’s plane was reported to have the top-turret right gun inoperative, and a nose-turret left gun charging handle malfunction. The position of the plane in the formation was the right side of the left wing at the rear of the formation. This was called “tail-end Charlie,” and was a very vulnerable position in the formation to attack from enemy fighters.

All planes returned to base without casualties. This was a very “easy” mission compared to the next one to Fredrichshafen two days later. In the flight records, it was indicated that Ace flew 8:50 as first pilot.

In order the show the magnitude of the bombing effort at this time, records show that on this day there were three different forces involved.. The 392nd was part of the third force which was directed to the target of Fredrichshafen. Other targets were factories and airdromes at or near Munich and Augsburg. There were a total of 793 bombers airborne this day but due to some assembly problems only 742 actually were dispatched, 222 B-17s in the first force, 281 B-17s in the second force, and 239 B-24s in the third. In regard to fighter support, 19 U.S.A.A.F. fighter groups of the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces and eleven Spitfire Squadrons of the R.A.F. participated in this operation and three P-47 groups flew double sorties. Of the 968 American fighters airborne, 868 were credited with sorties, 287 P-47s and 79 P-38s on the penetration, 135 P-51s and 46 P-38s through the target areas and 321 P-47s on the withdrawal. R.A.F. withdrawal support totaled 130 Spitfires. Total losses for this day included 23 bombers (18 B-17s and 5 B-24s). Battle damage was sustained by 156 aircraft, including 39 cases of major damage. Claims by the bombers against enemy aircraft amounted to 68 destroyed, 32 probably destroyed, and 43 damaged. Most of the losses, damage, and claims were by the first force whose target was mainly Augsburg. From the supporting fighter force, 12 aircraft were lost, while their claims included 78 destroyed, 7 probably destroyed, and 33 damaged, including 1 destroyed and 13 damaged on the ground.

The above description illustrates the magnitude of the air war being waged at this time. Through most of this narrative, I have and will focus on the operations of the 392nd only. This usually involved twenty-some bombers with each mission.

The next day (Mar., 17) Ace was scheduled to fly a mission in aircraft #371, but the mission was scrubbed due to weather.

On Mar. 18, the 392nd suffered the heaviest losses in both aircraft and crew of any other mission of the war. Ace was in on the briefing for this mission but was scratched at the last minute. This mission was also to Fredrichshafen, but the enemy was waiting for them this time. Of 28 planes in the group, fifteen aircraft and crews would be lost and nine other ships damaged by fighters and flak. A total of 154 casualties resulted from this mission. Four planes aborted due to mechanical or other problems prior to reaching the target and two planes collided over France, with both planes going down. Due to difficulty in coordination in timing with fighter escorts, the remaining planes were attacked by 60-75 German fighters. During the air battle and flak attacks that lasted about 35 minutes, 12 more planes were lost. Seven planes returned to England, all with extensive bomb damage. Lt. Bassett, who later would be the Navigator on most of Ace’s missions, flew with Lt. Ellison, but their aircraft aborted following the mid-air collision over France. After this mission, the group only had 13 planes, and many of them were badly damaged.

Still, three days later, 13 Liberators from the group participated in a mission to Watten.

Mar. 26, 1944: Mission #3

Target: Febvin Palfart (No-Ball)

The label of a target as “No-Ball” indicated that it was likely to a rocket launching site and was a rather short mission, usually near the coast of France and less resistance was usually expected. Sometimes, however, unexpected heavy enemy flak or aircraft was encountered. There were no “easy” missions.

The group was originally assigned the target of Oscherslehen, but at the last minute the target was changed. At 1215 hours, 24 aircraft began take-offs. The target area was visible and bombing results were excellent. One aircraft and crew was lost to AA fire. No enemy aircraft were seen but AA was intense and accurate. Seven other aircraft had battle damage. Ace flew in aircraft #131 in right “tail-end Charlie” of the high block. Hurdle, who was regularly in Ellison’s crew flew as the Bombardier. The total flying time was 4:35.

It would be almost three weeks before Ace and crew would fly another mission. His flight record indicated that some time was spent in practice flights and time on the Link Trainer. In a letter to Homer of April 5, he indicated that he had been on leave to London and that he and Wendorf Berry, who was stationed in England, were planning to get together. He also asked Homer how the name “Queen Mary” would sound for their plane. Obviously, this would be named after Jo. No naming of the plane occurred, however, as far as could be determined.

Normally, a crew was assigned to one particular plane and flew that plane only, unless it had mechanical problems or had been damaged so that it could not be flown until repaired. This is why they often picked names which had some specific meaning for that crew. Ace and crew seemed to have been given a specific plane as indicated above and in another letter where he had written that he and crew had spent an off-day cleaning up the “ship“. The statistics gathered in studying the missions however indicate that Ace flew eleven different planes in 17 missions. The most any one plane was flown was 4 times. This was plane No. 136 (A-Able), and was the plane flown on the last mission. Possibly battle damage was sufficient to prevent the assigned plane from being flown each mission.

A mission, which turned out to have embarrassing consequences and international complications, occurred on April 1. Ace was not included in this mission. The target was supposed to be Ludwigshafen’s chemical works. Twenty-three planes took off at 0645. In route to the target, the lead ship, with the lead navigator in charge, somehow made an error in navigation with heavy cloud cover and the Group’s aircraft were led some 120 miles southeast of the briefed target. When they dropped their bombs they were approximately 10 miles into neutral Switzerland. Upon returning to base they learned that the bombs had landed near the Swiss city of Schaffhausen. A total of (1184) 100lb. bombs had been released in the area. No casualties occurred with the 392nd, but some planes suffered anti-aircraft fire damage on the return trip. Needless to say, on returning there was a lot of explaining to do-especially for the lead ship.

A story was told to me by Judson Berry in 2003 which concerned this particular mission. He said that in the mid 1950’s he was in Germany for an extended period in work-related duties and he and his wife Mary Lou had during the summer of 1954 gone on a little trip and had been in Schaffhausen, Switzerland for lunch. Of course, they knew nothing of the mission which had occurred on April 1, 1944. The waiter in the restaurant asked if they were English and they told him that they were Americans. The waiter said they should not tell anyone because about ten years before their city had been bombed by the Americans. Some sources have said that this bombing may not have been the accident it was purported to be, since there was the possibility of factories located there which may have been supporting the German war effort.

Heavy casualties occurred for the 392nd on missions of April 8, 9, & 11 to Brunswick, Tutow, and Bernberg. A total of seven planes and crews were lost with another plane lost when it crash landed in England with all crew surviving. Two planes were lost due to a mid-air collision and in another tragic accident, a plane was hit by the bombs from a plane above.

April 22, 1944: Mission #4

Target: Hamm

This was one of the first missions flown late in the day with 27 aircrews taking off at 1530. This meant that return would be after nightfall. During the bombing run on the marshalling yards at Hamm, the leading ship was hit by AA fire. This caused the deputy lead ship to take over, however it was then too late to bomb the assigned target. The first section of Group ships continued around to bomb a Target of Opportunity believed to be the airfield at Chievres, Belgium, southwest of Brussels. The second section made a 360 degree turn and dropped on the Primary target of Hamm with good results. Shortly after, this group was attacked by about 60 single and twin engine enemy fighters. AA fire was also severe and accurate between fighter attacks. The group suffered 26 casualties and lost two aircraft. A total of 17 planes received battle damage. Ace flew in aircraft number 415 in the first section. Seven to nine enemy ME 109s attacked the plane and Podolski was credited with destroying one. Podolski was listed as the nose-gunner on this mission.

Corbett Miller, listed as the tail-gunner on this mission, was wounded. In talking with a nephew of Corbett Miller in October, 2003 in Somerset, Pennsylvania, I was told that Corbett could not get up from his tail-gunner position on the return flight because his blood had frozen his body to the seat. This would be the last combat mission for Miller, as his wounds to his back and hip were severe. I was told that he never fully recovered from the wounds after the war. At the end of this journal there will be additional information about Corbett Miller.

This was the first mission which Lt. Bassett was assigned as Navigator. The aircraft landed after dark and it was on this date that enemy aircraft followed the returning bombers home to England and hit various Group bases with low-level attacks. The 392nd, however, was not one of the groups attacked, either in the air or on the ground. The records of the 2nd Division indicate that 10 aircraft were damaged before landing, 2 were damaged on the ground and 8 aircraft crashed or crash landed, all attributed to the enemy intruders. Personnel casualties attributable to the enemy intruder action were: In air: 7 killed, 17 wounded, and 1 missing (parachuted over water, lost); On ground: 1 killed and 5 injured; and by Crash or Crash Landings: 29 killed and 1 injured. This turned out to be a devastating end to the mission for several of the groups. There seemed to be only 10-15 enemy aircraft that took part in these attacks. Part of the problem appeared to be that since they were returning after dark, visual recognition was difficult and they did not know they were enemy fighters until they were very close. Also, there was a lot of preparation for landing, including much radio activity, so that warnings were often not heard. One wonders why this tactic had not been used more often by the German fighter groups.

The individual flight record for Ace show that this mission occurred on April 21. I assume this was a misprint, since the official mission reports show April 22. The total time flown on this mission was 4 hours and 10 min. with one hour being on instruments.

On April 24, the target was Leipheim. At 0900, twenty-six aircraft began take-off. Ace flew in aircraft #617 and they experienced a left landing gear problem (would not stay retracted). Due to this problem he had to abort the mission and landed on another airfield near London. Anderson flew as the Navigator and Wimberly was the replacement for Miller. The bombing group lost two planes on this mission and suffered damage to four others. No sortie credit was given to Ace’s crew since they had to abort the mission.

According to Individual Flight Records, Ace flew a combat mission on this date, however mission reports indicate no mission other than the one to Leipheim. The Flight Records indicated first pilot times as 1:25 for the non-combat mission and 3:15 for the combat mission. In numbering the combat missions, I have listed this as Mission #5. After completion of five combat missions, Ace was awarded the Air Medal.

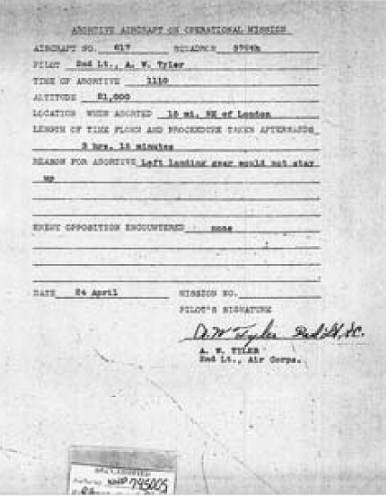

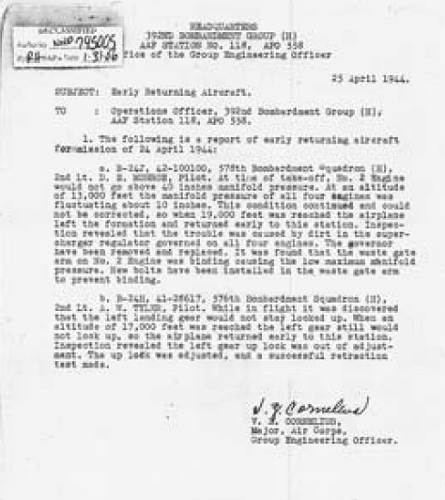

Copies of the official forms used for aborted missions are shown on following pages (photos 24 and 25).

24 Abort Mission Papers

25 Abort Mission Papers April 25, 1944: Mission #6

Target: Wizernes (NoBall)

The launch of 23 aircraft occurred at 1140. Bombing effectiveness was unobserved due to a heavy undercast (since clouds were under planes, instead of overcast, it was called undercast) of 10/10th coverage. No enemy aircraft were encountered and there was no AA fire. No aircraft were lost as they returned to base around 1500 hours. Ace flew aircraft #772 and was in the middle of the formation. Anderson was the navigator for this mission. The 14th Combat Wing maintained gas consumption records for each mission.

It was interesting to note that on this mission, the gas consumption for Ace’s plane was 364 gal./hour, while the average was 290. On the mission of May 8, however, his gas consumption was the lowest in the group (266 gal./hour, with the average being 323). I would imagine there are a lot of factors to consider, such as position in formation, altitude, model of plane, etc.

April 26, 1944: Mission #7

Target: Gutersloh

Take-offs commenced at 0550 for 26 crews. Due to 10/10ths undercast no bombing occurred. No enemy opposition was encountered, but on the return one aircraft was damaged by flak. The aircraft returned about 1045. Ace flew aircraft #371 and Bassett was the navigator, Crowley was ball turret gunner and the tail gunner was Riley. The formation position was high right just behind Lt. Ellison in #131. There was a total of 238 aircraft from 4 combat wings dispatched. Two groups and one squadron of P-47s, one group of P-51s and one group of P-38s gave good support.

April 27, 1944: Mission #8

Target: Chalon-Sur-Marne

This was the second of two missions flown by the 392nd on this day. The first mission had returned around noon, and the second group of 26 aircrews took off about 1525 hours. Bombing occurred with pin-point accuracy. No enemy aircraft were seen but heavy AA fire was encountered when group was returning. One aircraft was severely damaged and crash-landed in England (#509 of the 578th Squadron). The heroics of the Co-pilot of this plane was recognized subsequently with the award of a Distinguished Flying Cross for his efforts to save the ship and crew on this raid. With the aircraft badly damaged by AA fire, the Co-pilot, 2nd Lt. G. C. Marshall, had to take over control of the plane. The only crew member with an undamaged parachute, the Radio Operator, had bailed out. With dead and wounded aboard, Lt. Marshall flew the crippled plane back to England where in crash landing, five more crewmembers were killed. A total of 17 other planes were damaged by the heavy AA fire. Ace flew #027 and the plane received moderate flak damage. The Navigator’s log was shattered by flak and blown away. The position in the formation was again behind Lt. Ellison in the lead block.

This mission of April 27 was the fourth day in a row for Ace and the 5th in one week. There may have been an additional mission also, according to the Individual Flight Records. It was not surprising that the next mission Ace participated in was not until May 4. Some time off was definitely earned.

The mission of April 29, 1944 to Berlin was the second most costly of all for the 392nd.

A total of eight aircraft and 77 aircrew member casualties occurred. Persistent attacks by enemy aircraft and heavy AA fire took its toll on the group. In addition, one plane of the

576th veered out of position when under attack and collided with another plane, causing both to go down.

On May 4, with the target being Brunswick, twenty-five aircrews took off at 0700. The weather conditions were very poor as it seemed to be much of the time. Probably due to the coming invasion of France, however, they were trying to get this mission in. There were a total of 18 missions flown in April and 20 in May. Days missed were probably due to weather or due to the fact that planes had to be repaired. Because of the very bad visibility, very few planes were able to form up in assembly. Only six of the twenty-five planes joined formation and continued far enough to be given credit for a sortie before being recalled from the mission. According to the Individual Flight Record, Ace had a total of 5:00 flying time which is what is recorded as the time for those recalled. From this, one would assume that his ship was one of the six making formation, however no combat credit was given.

May 7, 1944: Mission #9

Target: Munster

The weather had continued to be very bad on the 5th and 6th, but on the 7th the plan was to have two targets. Plan “A” target was to be Gutersloh, an airfield, while Plan “B” called for bombing at Osnabruck. At 0655 hours, 27 aircrews began take-off to execute

Plan “B”. The weather to the target was very poor and target area was 10/10ths undercast and the lead ship led them to another target - Munster. Results of bombing was unobserved. Approximately 40 enemy fighters were sighted, but none were encountered.

The flak was intense and accurate during the bombing run, but no aircraft or crew casualties resulted. Thirteen planes came home with flak damage about 1345 hours. Ace flew in #617 in the low block to the rear. Podolski was the bombardier for this mission.

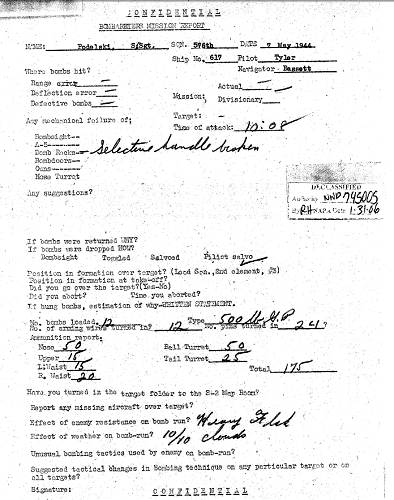

Below is a copy of his report on the mission (photo 26).

26 Mission Report

Click image for larger viewMay 8, 1944: Mission #10

Target: Brunswick (Braunschweig)

Again crews were briefed for two plans and Plan “B” was Brunswick. At 0610 twentyeight planes began take-offs. Due to 10/10ths undercast again, the results of the bombing were not observed. Flak was intense with 11 ships suffering battle damage. All returned around 1300 hours. Ace flew in aircraft #772 which suffered some flak damage. Of almost seven hours flying time, Ace flew about four hours and the Co-pilot (Ricci) flew three hours. This pattern of sharing flying time with Ricci would continue for most of the remainder of missions. After this, his 10th mission, an oak leaf cluster was added to the Air Medal. An interesting part of the 14th Combat Wing report involving the 44th BG was described as follows: “At 0852 hours over Zuider Zee B-24 with yellow rudder with black horizontal bar across rudder observed going in same direction at 11 o’clock low.

A/C later observed turning off to left. At 0902 hours at 52 deg. 37’N. 05 deg 38’E., yellow barrage balloon observed at 2000 ft. Two chutes seen over target. At 1027 hours

52 deg. N. 10deg. E., 2 B-24s from another group seen to collide, one exploded and both seen going down-3 chutes observed. At 1125 hours shortly after crossing the coast out at

52deg 42’N. 04deg. 38’E. B-24 ahead seen turning off to left. P-51s heard over VHF saying they were coming back to identify this A/C. A/C heard replying, “No, you’re not.” After this P-51s were seen shooting this B-24 down.” Evidently, this was a captured B-24 which had flown along with the group for some time. There were some attacks by enemy fighters, with the 392nd destroying one. The attacks on other groups, however, were much more severe, with the 389th claiming 17 enemy planes destroyed.

May 9, 1944: Mission #11

Target: St. Trond Airfield

A late Field Order was received at 0200, so briefing was quickly held between 0245-0315 hours for 28 crews. At 0605, the planes began take-off. Upon reaching the target,

(1358) 100 lb. bombs were released with excellent results. No enemy aircraft were encountered and flak was light, although some planes suffered minor damage. Ace flew “tail-end Charlie” of low left group in #136 (on Lt. Ellison’s right wing). This mission was flown with a crew of nine. The 392nd Bomb Group led the 14th Combat Bomb Wing with three squadrons and the 44th Bomb Group was second with two squadrons. The first squadron of the 392nd laid down a very good pattern on the briefed target, getting excellent results. The third squadron (Ace’s squadron) laid down an even better pattern with excellent bombing results while the second squadron laid down a very poor pattern short of the briefed target, accomplishing fair results.

May 10, 1944: Mission #12

Target: Diepholtz

This mission was to be against an airfield in Diepholtz. Due to extremely poor assembly weather, however, the mission was scrubbed. Ace had to abort this attempted mission because of a malfunctioning radio. According to the Ind. Flight Records, he was given credit for a sortie and a total of five hours flying time was recorded.

Records indicate there were several days before flying again. On May 14th , Ace was listed as flying 1:15 with another crew. I assume that this was a training flight for a new crew. On May 20th, Individual Flight Records indicate 3:25 flying time, which was probably a training flight, since there was no group mission record for that day.

May 23, 1944: Mission #13

Target: St. Avord Airfield

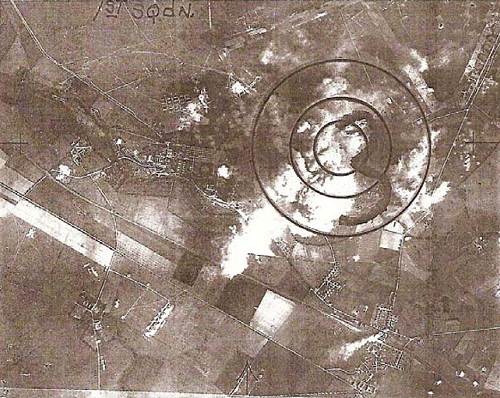

Briefing was held at 0130 with 30 aircrews. At 0500, thirty planes took off under good weather, for a change. Bombing results were excellent. No fighter reaction was encountered, but flak was moderate and fairly accurate. Nine planes were damaged, but there were no casualties and planes returned to base about 1300. Ace’s plane was #136 and again flew low left tail-end. Below is a photo of the bombing results of the two 492nd squadrons. One can see that the smoke is coming up in the target area. Just above this the runways are visible (photos 27 and 28).

27 Bombing Run

28 Bombing Run May 24, 1944: Mission #14

Target: Melun Airfield

The mission of May 24 was scheduled for Melun Airfield. Ace, flying in #045 was forced to abort this mission due to aileron control sticking. Individual Flight Records indicate, however, that he was given combat credit and actually put in 3:25 flying time as part of the mission. After aborting, he evidently flew additional time checking out the controls since records indicate 4:30 flying time with two landings. The groups bombing was very successful and no enemy fighters were seen. Flak was moderate but inaccurate with 11 planes having some damage. No casualties were suffered and they returned to base around noon. The report of the aborted aircraft is shown below (photo 29).

29 Aborted Aircraft Report

Click image for larger viewMay 27, 1944: Mission #15

Target: Saarbrucken

A total of 24 planes went over target and the bombing run was very successful. No enemy planes were encountered. Flak was fairly accurate and 11 planes were damaged but there were no casualties. All aircraft returned about 1845 after a mission of over eight hours.

Ace’s plane was #136 and suffered some flak damage. His position in formation at the target was the left high block. A second oak leaf cluster would have been added to the Air Medal after this mission.

May 28, 1944: Mission #16

Target: Zeitz

The synthetic oil plant near Zeitz was the target. At 1044 hours 26 aircrews took off. Bombing results were excellent. Nine aircraft suffered minor damage and there was one casualty. Ace flew in aircraft #433 and was high and right of the 44th group in formation. All planes were back around 1800 hours.

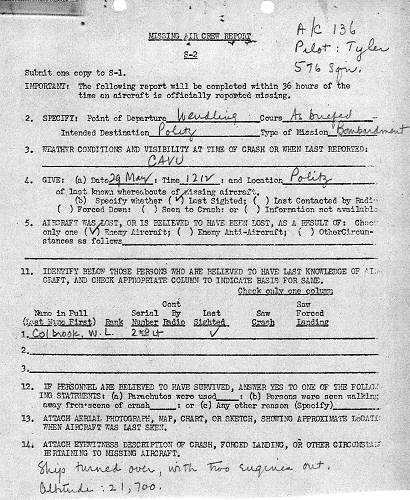

May 29, 1944: Mission #17

Target: Politz (Stettin)

Again the oil refineries were the target as an increased effort was being made to reduce Germany’s capabilities prior to D-day. It was the first raid on Politz, a heavily defended target. This was the location of Germany’s largest synthetic oil refinery at this time. Four B-24 Combat Wings (439 planes) took part in this operation. This would turn out to be the fourth most costly in planes and seventh in personnel casualties for the 392nd. At 0749 twenty-seven planes took off from Wendling. One plane was forced to abort due to mechanical problems. Just prior to reaching the target, an estimated 75-100 enemy fighters attacked the group. These included ME-109s, FW-190s, JU-88s and at least one twin-engine ME-410. The fighter attacks lasted for about thirty-five minutes and started 50-75 miles before reaching the target.

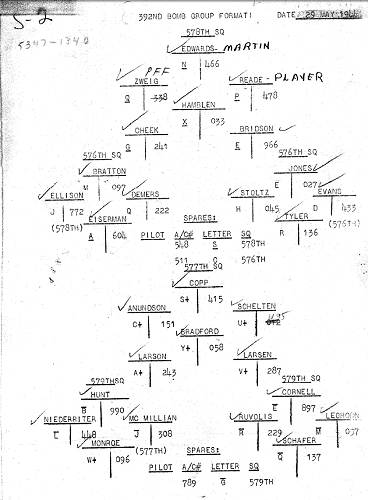

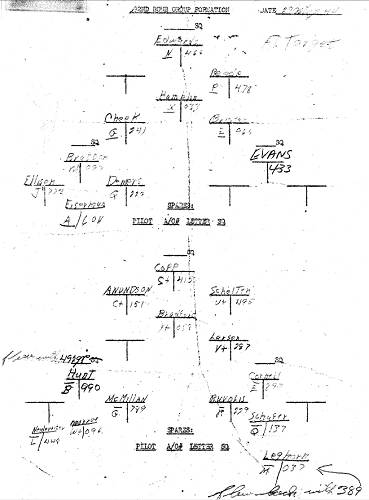

Formation after assembly and over target are shown in the following two diagrams (photos 30 and 31):

30 392nd Bomb Group Formation

Click image for larger view

31 392nd Bomb Group Formation

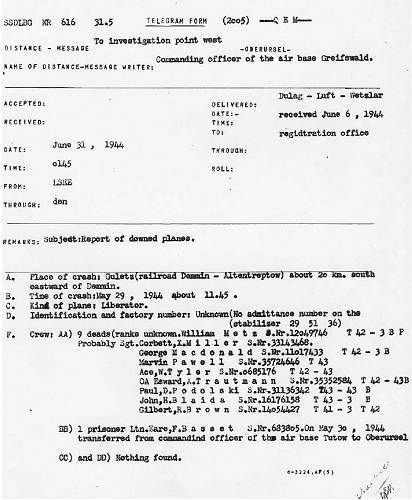

Click image for larger viewAce’s plane was #136 and was positioned at the tail end on the right of the lead group. The enemy fighters were well-coordinated in mass attacks through the formation and also shot rockets into the formation from the rear. According to eyewitness reports, Ace’s plane was seen under fighter attack at 1212 hours and had two engines (out) feathered. It appeared to roll over on its back and went into a steep dive from an altitude of 21000 ft. One chute was seen from the plane. This was the Navigator, Earl Bassett.

In a conversation with his wife in 1999, she told that he landed near the railroad and was taken prisoner by the local police. In an interrogation report in 1945, after being released from prison camp, Bassett corroborated the report of how the plane went down. Bassett had related to his wife that there had been a fire, likely an oxygen fire. The main reason Bassett was able to get out of the plane was the Navigator is closest to the hatch used for escape and it is only large enough to barely squeeze through with a chute on. The other means of escape from the plane was through the bomb bay doors. Earl Bassett returned to live in Rhode Island after the war and died in 1997.

The Stoltz plane (045) was positioned just in front of Ace’s plane and also went down at about the same time. No chutes were seen. Evidently, this plane was able to recover somewhat, because the crash site for this crew was 60-80 miles west of Gueltz. One report indicated that it was headed to Sweden. It crashed however at 1240 and all the crew were killed. It is likely that German fighters attacked it since it was already a damaged plane. The Eiserman plane (604) crashed near the Baltic Sea, after the bomb run, and 8 chutes were seen. It was later reported that all the crew were taken prisoner, but one later died. The Larson plane (243) also went down and 7 chutes were seen. Final reports, however, indicated that all 10 crew members were KIA. Three of these were killed on the ground by police or citizens. Two other planes crash landed in England and the crews were safe. Eight other planes had battle damage-some severe. One plane returned with two engines out and the nose turret blasted apart.

The narrative of the command pilot seems to agree with other reports about when the four planes went down at or near the target. He indicated that the first plane to go down was that of Larson. This occurred about 20 minutes prior to release of bombs over target. The Eiserman plane went down about 1209 after releasing bombs. The Stoltz plane and Ace’s plane went down about the same time (1212), which was over the target and about the time the lead navigator reported bombs were released. So it is probable that bombs had been released over the target, but since they were under attack, they may not have been.

Evidently, Ace’s plane was hit during the first of three waves of attacks of fighters. According to some witnesses, there was no Allied fighter support until after the target and the enemy fighters had left. This was likely due to a timing error in arrival of the fighter escorts. Reports of the 2nd Air Division, however, indicate that the two leading combat wings going to Politz were first attacked by approximately 40 FW-190s. Those were engaged by one Squadron of the escorting P-51 group. Immediately thereafter, and in the vicinity of the Initial Point, a second formation of approximately 60 single-engine fighters operating in two waves intercepted the same two Combat Wings as another formation of 20 enemy aircraft attacked one of the P-51 squadrons. These concentrations quickly saturated the defense afforded by the one P-51 Group (42 aircraft) and enabled a large proportion of the enemy fighters to engage the leading Combat Wings without opposition as they continued through the target area at Politz. So while one enemy fighter group was attacking the P-51 escorts, the second enemy fighter group was left to attack the bombers without opposition.

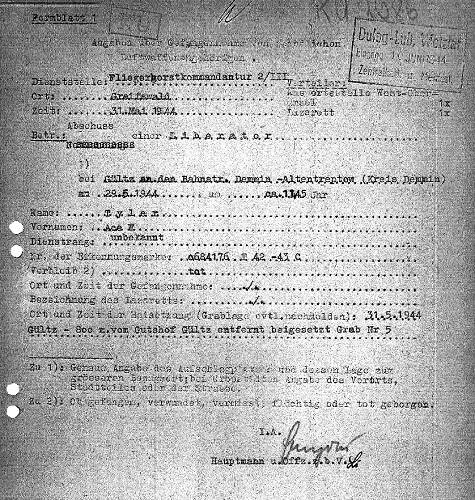

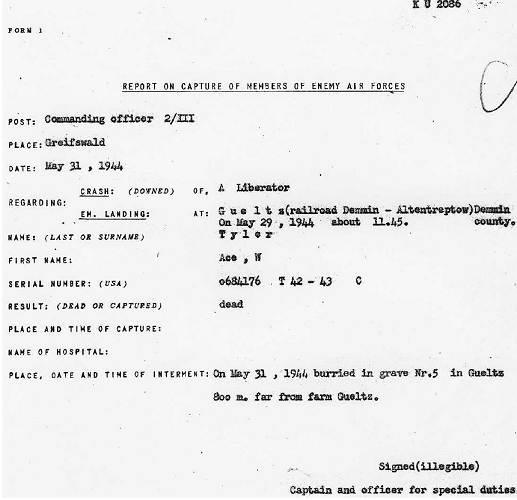

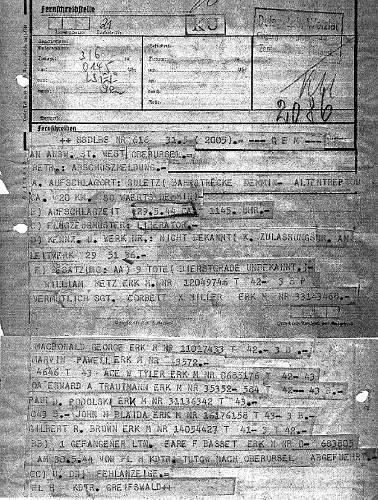

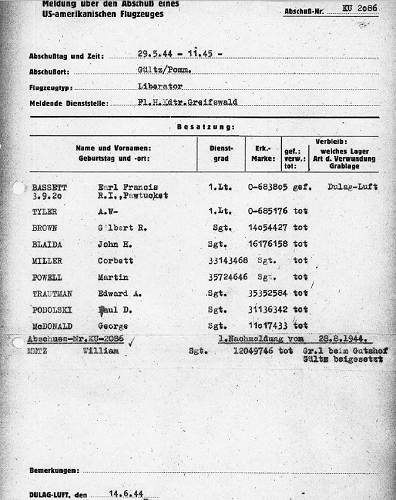

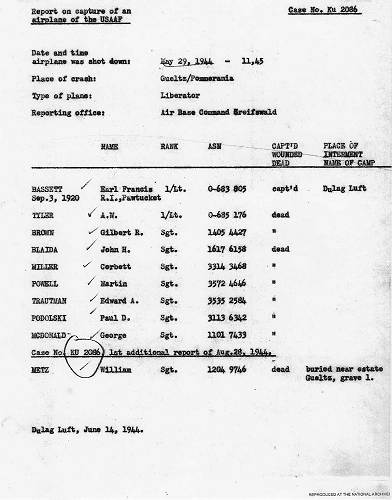

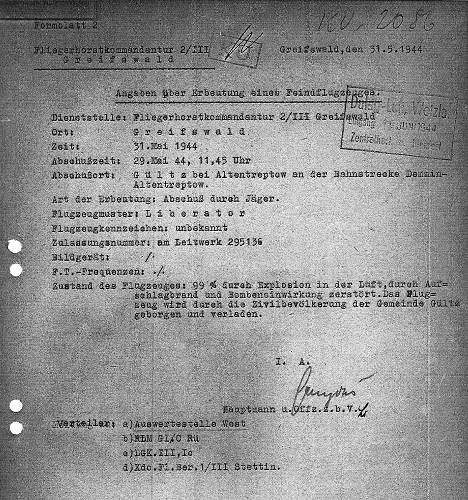

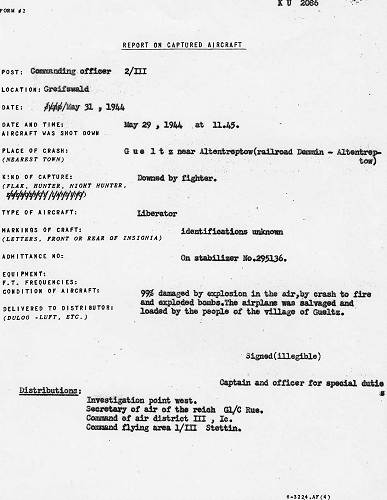

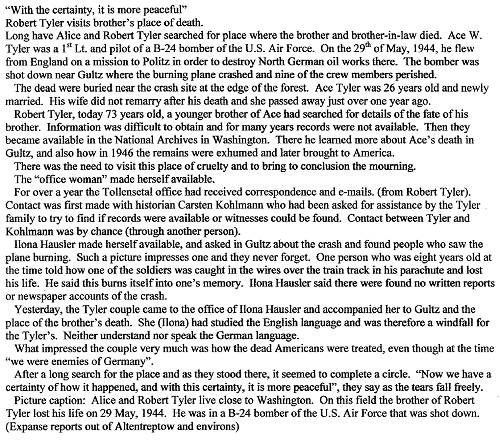

According to the German reports (see copy of report which follows), the recovery of bodies from Ace’s plane occurred at Gueltz near Demmin and they were buried at Gueltz, 800 meters from Gueltz-estate. Ace’s body was placed in grave #5. “Dog-tags” of Ace, Bassett (taken prisoner), Podolski, McDonald, Troutman, and Blaida were returned in German files and are located in the National Archives at College Park, Md. The crash site was near the village of Gueltz, near the railroad line between Demmin and Altentreptow.

Seven of Ace’s crew had flown on the first combat mission of Mar. 16 (Tyler, Ricci, McDonald, Metz, Brown, Podolski, and Blaida). Troutman had joined the crew for several missions, but this was only the second one for Powell. Bassett was not the Navigator on the original crew but had flown several missions with this crew. He was part of the original Ellison crew.

There is some inconsistency in the German reports and later casualty reports. The German reports list Corbett Miller as one of the casualties, however later reports do not list him. He had been injured on the mission of April 22 and did not fly again. It is likely that since there was a copy of Sgt. Miller’s pay record found on the plane or on one of the bodies (this was included in German files), they assumed he was one of the crew. The actual German report does say “probably” Sgt. Corbett Miller. Powell was likely the replacement for Miller. Another factor that contributed to this confusion was that Joe Ricci’s confirmation of death did not occur until much later (probably due to difficulty in identifying the remains). So his body may have been mistakenly identified as Miller’s by the Germans.

Further details of the crash were learned through correspondence with individuals from the Gueltz vicinity and through a visit to that area in October, 2003. This information is given in a separate section later in this journal (The Crash). Also, other details about the crash were gathered through the Individual Deceased Personnel File.

In order to further elaborate on this specific mission, however, I have chosen to use the description given by Lt. Ellison to show, from his perspective, what happened during this mission to Politz. These are the words of Lt. Ellison:

“On May 29, our 28th mission was almost our last. At briefing the target was named Stettin, an oil refinery northeast of Berlin. A long, long haul! In later documents I noted that this target was called Politz. Anyway, it is the same place. We flew this one with two of our old crew missing, Hurdle and Bassett. Hurdle, having flown as squadron bombardier several previous missions, had completed his tour and was being transferred. Bassett had been assigned to Lt. Tyler’s crew for this mission. I had a replacement enlisted man in the nose turret and he was scared almost to death. The timing must have been off for we missed our fighter escort and it is just what the Luftwaffe had been waiting for. About 15 minutes from the target and for approximately 30 minutes thereafter, we were under attack by 100 to 150 FW190s, JU88s and ME109s. During the first three attacks the ME109s and FW190s went through the formation and between the B-24s, thereby creating havoc. They literally shot the 392nd to pieces. German pilots came so close that I felt as if I would recognize them if I met them on the street. We lost six to eight of the 27 planes we started with and I thought that we would be among the missing that night. One 20mm came through the front windshield and missed my head by a small fraction of an inch, went on back and ripped some clothing from Samples in the top turret. We also had 20mm shells in both spars which buckled the wings, but by the grace of God, did not ignite the fuel. Also, we had a cylinder shot out of our number two engine which made it inoperable. Number three engine was hit and running rough but I could use it about half of the time. I could not feather the propeller on the number two engine at all. The enemy fighters must have run low on gas because they withdrew.