|

Monday, November 10, 2008

Progress Notes

A couple of weeks ago I listed the names of the quilt raffle winners at our Chili dinner. The winner of the large quilt was Dana Maloney of North Carolina (photo 01).

01 Dana Steen Maloney - October 2008

Dana is the daughter of Waldo Sherrill Steen, originally of Iberia, who had a long career in the U.S. Air Force, but now in retirement lives in Texas. Sherrill and Dana have been very supportive of our museum building program. Dana’s grandfather, Waldo Amos Steen (photo 02), was a life long resident of Miller County, mostly living in Iberia where for many years he owned and operated a turkey farm.

02 Waldo Amos Steen and Great Grandson Dylan Waldo Maloney - 1993

One of the distinctive features of his farm was the large barn on top of the hill which had one of the feed storage bins placed off to the side on top of the roof (photo 03).

03 Waldo's Grain Barn

This structure is still there today and easily can be seen from Highway 42 on the south side about four miles west of Iberia.

Dana sent me a very interesting story about how her grandfather, Waldo, once lost his pocket watch. Many people around Iberia especially will remember Waldo so I thought this story would be of special interest to them:

My Grandpa Steen’s Pocket Watch

Dana Steen Maloney (born November 15, 1961 in Iberia, Mo.)

Written October, 2008

Grandpa Steen’s pocket watch was connected to his bib overalls with a leather strap. He looked at it often and used it to attract small children to his lap. I sat on his lap for a closer look at Grandpa’s watch until I was at least ten years old. Grandpa always smiled when he saw me coming. Together we examined the watch closely. I liked to feel the vibration of the “tick tock” when I put it close to my ear.

Grandpa and Grandma Steen had 9 kids in 11 years. They worked hard to feed, clothe and shelter their family. Dollars were scarce, so Grandpa was extra proud of his watch. About 30 years before I was born, during the Depression, Grandpa didn’t have a leather strap for his “dollar pocket watch.” Yes, it really cost a dollar. That was a lot of money in those days. An ambitious man in Iberia, Missouri, might be able to earn a dollar a day cutting hay or harvesting wheat, but those opportunities were few and far between.

One cold November day, Grandpa was cutting and shocking corn in a 15-acre field. That’s about the size of 15 football fields. He used his 14” corn knife to hack the brown stalks that were standing in the field. When he had an armful, Grandpa tied the stalks (which held ears of corn) together and stood them up side by side in a large, tight circle called a corn shock. At the end of the day, the 15-acre field was scattered with corn shocks that were four feet across and six feet high. It was getting late and he was getting hungry when Grandpa looked for his pocket watch to see when he should go home for supper. He looked all around, but the watch was nowhere to be found.

Successful farmers have determination and Grandpa had plenty of determination. He went home to eat supper and ponder the best way to solve his problem. Every farmer knows that the wind dies down at night and that sound travels best on a cold night with a hard freeze. It was quiet that night because most birds had already headed south and frogs were hibernating. Grandpa knew it would be a clear sky with lots of stars and frost on the ground the very night he needed to find his watch.

With his kerosene lantern and heavy coat, Grandpa trudged back to the field when the moon was rising. One at a time, Grandpa went to each and every corn shock. He got down on his hands and knees and put his ear to the dried stalks and listened for the tick tock. His hands were freezing but he wanted his watch. After going through many, many shocks in the 15-acre field, he thought he heard his pocket watch ticking. He tore the shock apart. With his lantern in one hand, he used his other hand to rummage through the hard, dried stalks until he felt the metal case of his watch (photo 04).

04 Grandpa Steen's Dollar Pocket Watch

Grandpa wound his pocket watch every morning after he washed up for breakfast. He turned the little round knob clockwise until it felt tight. If he hadn’t found his pocket watch before breakfast it would have stopped ticking and he never would have found it. After that close call, he found the means to buy the leather strap that fastened his watch to the top of his bib overalls.

The odds of Grandpa finding his watch in that 15-acre field were about the same as the odds of finding the proverbial “needle in a haystack.” But Grandpa’s fortitude didn’t waiver. After a day of hard labor; he walked miles and dug his hands through corn stalks to find his treasure in the middle of a long, cold night. I would like to think I have some of my Grandpa’s perseverance; I’ve just never had to find it.

Thanks Dana.

Further information about Waldo, Dana’s grandfather, can be found in his obituary which I copy here:

Obituary: Jefferson City Post Tribune, Saturday, April 8, 1995

Waldo A. Steen, 88, Eldon, died Thursday at Eldon Health Care Center. He was born February 12, 1907 in Iberia, a son of Frank and Ella Wall Steen. He was married April 17, 1932 in Brumley, to Eula Popplewell, who survives of the home. He lived in Iberia until 1972 when he moved to Eldon. He was a poultry grower and a carpenter. He was a member of Hickory Point Baptist Church near Iberia. In Eldon, he became a member of First Baptist Church.

Other survivors include: two sons, Sherrill Steen, Mt. Laurel, NJ, and James Steen, Eldon; six daughters, Carol Elseman, Barnett, Gereldine Atwell, Dixon, Janet Steen, San Antonio, Texas, Alice Tyler, College Park, MD, Marilyn Whitaker, Iberia, and Eula Maye Bond, California; two brothers, John Steen, Evansville, Indiana and Paul Steen, Iberia; two sisters, Virgie Smith, Portland, Oregon and Icie Evacko, Iberia; 22 grandchildren and 42 great-grandchildren.

One son, Roger Steen, preceded him in death in 1951.

Services will be at 1:30 p.m. Sunday at First Baptist Church. The Rev. Randall Bunch will officiate. Burial will be in Hickory Point Cemetery, Iberia. Visitation will be from 4-8 p.m. today at Phillips Funeral Home, Eldon. Memorials are suggested to First Baptist Church of Eldon or to the American Heart Association.

Some of the kinds of narratives I like to read most are first person ones in which the author writes about experiences he or she have lived or observed themselves. I really encourage readers who have personal narratives written by themselves or their own relatives or friends about Miller County happenings of the past to send them to me so I can share them with all who read this website.

Since some of my own relatives wrote down or recorded on tape their own Miller County experiences from the past it is convenient for me from time to time that I put their memories on our website. I realize that what my relatives experienced here is rather generic; that is, about anyone with roots in Miller County has relatives from their past who could have written the same things as mine would.

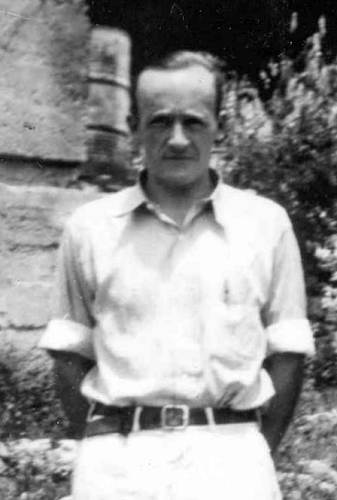

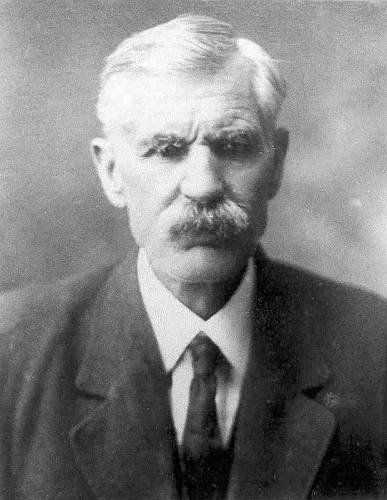

In January of 1980 my Uncle Arthur Bear (photo 05) recorded his autobiography which later was transcribed.

05 Arthur Bear

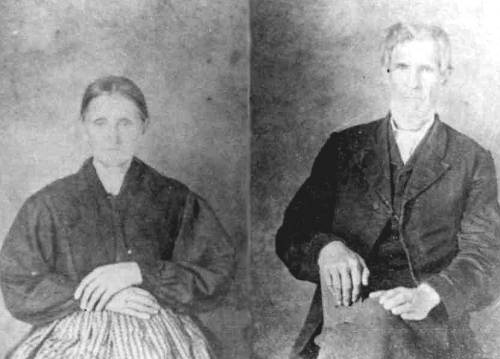

He was my mother’s brother and was born on the family farm near Dog Creek south of the Osage River on what is now Highway 52. The original home site was established by Arthur’s great grandfather, George Bear (photo 06), and amazingly, still is owned by descendants of the Bear family.

06 Elizabeth and George Bear

Roy Bear, the Bear descendant to whom the farm was passed, and who was born and raised here, passed away this year but his son, Robert, will carry on the tradition of the farm remaining in the Bear family. Robert and his mother, Doris (Myers) Bear, presently live in Grandview, Missouri.

Arthur early in his life in Tuscumbia had four different grocery stores. The first one was in the old post office building still standing downtown across the street from the river; the second was in the Jim Johnson building located on the river bank which burned; the third was in the old farmer’s exchange building, also located near the river a short distance down the street (which no longer is standing). After being burned out in the second store and flooded out in the third store Arthur moved up to the top of the hill to a building which still exists across from the bank. I mentioned this building a couple of weeks ago in my story about the Messersmiths’ as Charles Messersmith was the original builder. Finally, after the war, Arthur started a grocery store in Eldon named the “Sanitary Market” which was located on Maple Street across from the old Reed’s Department store. I always wondered if the name “Sanitary Market” was implying that in those days some of the grocery stores were dirty or something? After about a quarter century living in Eldon Arthur retired in the 1960’s. He spent much of his time playing golf and a couple years before he died in 2006 at the age of 96 he was given honorary membership in the Eldon Golf Club. Arthur and his wife, Lena (Brown), were well known in Eldon and had many friends there.

Copied here is Arthur’s story:

Reflections of Arthur Simeon Bear

January, 1980

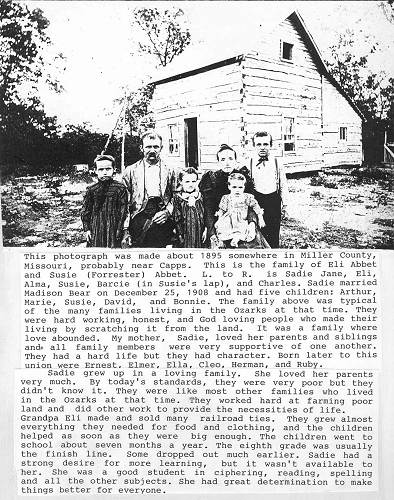

Some of my earliest memories were playing with Aunt Ruby Abbett at about age 4. She is six months younger. I also have early memories of Dick Wright the mail carrier. In 1914 we lived on the ridge about two miles from Grandpa Bear (photo 07) and perhaps 1 ½ miles from Grandpa Eli Abbett, my mother’s father (photos 08 and 09 of Abbett family).

07 David Christian Bear

08 Eli Abbett Family

Click image for larger view

09 AbbettFamily: Sadie, Alma, Barcy, Ella, Cleo, Herman, Charlie and Ernest

I would be at Grandpa Bear’s occasionally when Dick came by with the mail in his buggy pulled by a team of horses. He always asked me, “How old are you?” I can remember saying “four years old.” At that time Dad wasn’t financially able to have any transportation but horses, so we went everywhere on horseback. I can yet remember being bundled up in a blanket to keep me warm and held by one of my parents when we went by horseback to one of the grandparents in the winter. I also remember the first automobile I ever saw. I was four years old. Mother was real excited when she heard it coming, and we ran to the front porch to see it. I also remember the first one I ever rode in. Mother and I had gone to Granite City, Illinois, on the train to visit Aunt Alma (Abbett) Craven, her sister. While there we took a taxi which was my first experience in an automobile. It had a high chair for little ones. Another time on a rainy day, I happened to see a one legged man coming down the road on crutches. I was terrified. In the meantime it had started raining hard and he stopped at our home to get out of the rain. I slipped out without being seen and crawled under the house as far as I could get. Eventually mom found me but I would not come out. I asked her if that was the Devil. She assured me it wasn’t, that it was Syl Varner, instead. I guess I came out then. Another memory was my clothes. My dress suits up until 12 or 13 years of age were always knickers which were knee pants that buttoned tight above the knees then bloused down below the knees (photo 10).

10 Arthur Bear at Home Farm

Also, during the winter we wore wool underwear and wool socks…oh how they scratched! Mother knitted some of the socks from wool sheared from our own sheep. I can remember sister Marie’s birth very well. At that time we had only one bed, and I had always slept with mom and dad. When Marie (photo 11) came she took my place and I had to go to the foot of the bed. I felt mistreated and cried about it.

11 Marie Bear

Also while living on the ridge, I remember begging Dad to bring me some cheese from town (Tuscumbia). He did. When I was a little older, I was in town with Grandpa Bear, and he took me to Sam Johnson’s Restaurant for bologna and crackers which were my first (photo 12).

12 Johnson Restaurant Right Side During Flood

When I was about 5 ½ years old we bought a farm on Cat Tail Creek near where the present Miller County Nursing Home located later. The farm was purchased from George Lawson. I attended my first year of school at Bear School (photo 13), a one room rural school near Grandpa Bear’s farm.

13 Bear School - 2007

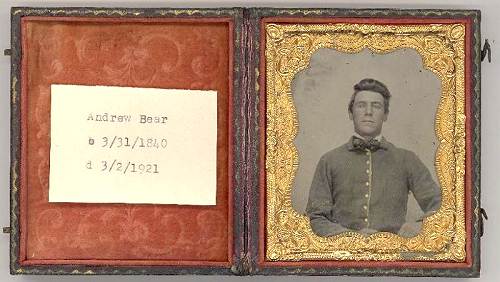

Lucy Watson was the teacher. She came by our house on horseback, and I rode behind her during the whole term. Uncle Andrew Bear (photo 14) and Aunt Cynthia and Billy, their bachelor son, were our nearest neighbors.

14 Andrew Bear

Billy was about 11 years older than Dad. (at age 56 Billy married Jennie Roberts) (photo 15).

15 Jennie Bear, George Billy Bear, Cynthia Bear, Arthur Bear, Roy Bear and Sandra Bear

Uncle Andrew at that time was about 75 years old. He was about 5 feet 10 inches in height and weighed perhaps 140 pounds He had white hair and beard, although it didn’t come down his chest as some old timers wore theirs. When weather permitted, he walked to our house every day for a short visit, and always had either a lemon drop or mint lozenge for each of us three children. He expressed the hope that he would live to hear my brother Dave talk because he was going to be a smart man. Dave, of course you will say, “It takes one to know one.” He always used a cane. We children always liked to visit Uncle Andrew and Aunt Cynthia. Marie and I were sent there when Dave was born. My great Uncle George (photo 16) and Aunt Jennie (Curry) Bear lived south of Uncle Andrew.

16 George Bear Jr.

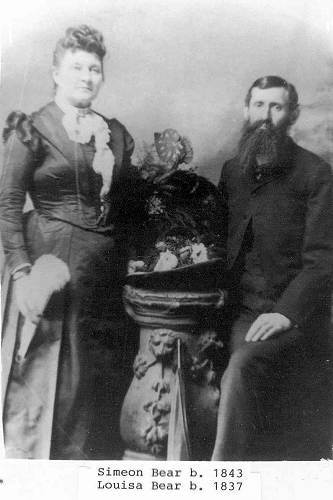

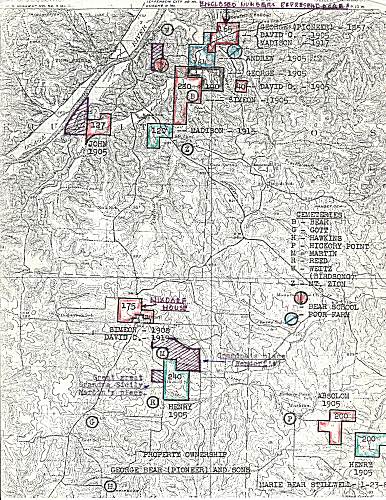

We moved to the original Bear homestead from Cat Tail Creek in 1915 and this farm was to the north of Uncle Andrew. Uncle Simeon (photo 17) also owned a farm near Uncle George, so this area was a Bear community (photo 18 Bear Family plot map).

17 Simeon and Louisa Bear

18 Bear Family Plot Map

Click image for larger view

My memory of Uncle George is almost nil though I was about 8 ½ years old when he died.

I guess we didn’t visit very much, even though the families were close knit. Also, Uncle George, at this time, had tuberculosis and was confined most of the time. He died at about age 69. I remember being at his home when Katie and Zack Stark were married. Also, on one other occasion when he was bedfast and had to have help getting his throat cleared. I remember nothing of his death and burial in the Bear Cemetery (photo 19).

19 Bear Cemetery

Uncle Simeon when I remember him lived at Ulman. Previously, he had owned the Carrol Abbott farm up the creek from Uncle George. I, being a namesake of Uncle Simeon, was a favorite. He raised sheep and made me a gift of two ewes and a ram which later increased to 18 to 20 sheep which we kept until we left the farm. The only recollection I have of Uncle Henry (photo 20) is that some of his children visited at Grandpa’s when their father died. I don’t believe that I was at the funeral.

20 Henry and Virginia Bear

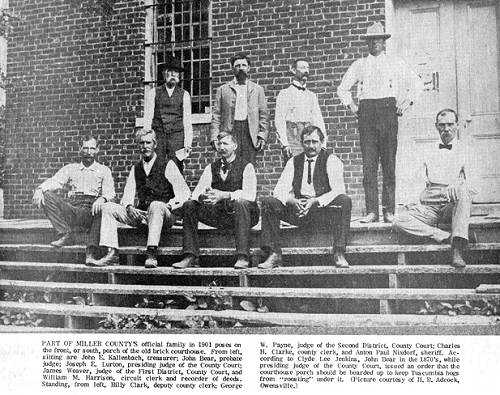

I don’t remember Uncle John Bear at all since he died in 1912. John was the oldest of the eleven children of Great grandfather George Bear (photo 21 of John at courthouse).

21 County Officials 1901 - John Bear 2nd From Left Seated

Click image for larger view

I remember Uncle Absalom well as I was about 21 or 22 years old at his death. He was about 6’ 1” tall when young and was powerfully built. I remember him as having real good sense of humor. I remember him coming to visit Grandpa when we were still on the farm (photo 22).

22 Absolum Bear at Home

I went to Bear School (see photo 13 above of Bear School) until midway through the eighth grade. We lived 1 ¾ miles from school. Marie and I walked it back and forth all the time. No school buses at that time. Bear School, when I went there was a fairly new concrete building, probably about 30 > 40 feet, and accommodated about 60 pupils with only one teacher. Our school board thought it was wonderful when they had enough money to keep school open for a 6 month term. Some districts could manage only 5 months. Teachers were paid 30 to 40 dollars per month. I remember one board meeting that was held at our house when they interviewed a prospect and hired her for $40.00 per month. In those days there would be some pupils 18 or 19 years old, some usually older than the teacher. Qualifications for teaching were not high. Anyone who could pass the teachers’ examination could teach whether they had ever been to high school or not. This created disciplinary problems. It was quite common for the older pupils to intimidate the teacher so that he or she would leave.

On many occasions, Grandpa Bear would reminisce about many things. I wish I had been more attentive. Being only four years old when his family left Ohio, he couldn’t remember much of the life there. He told me that after the sale, they took a steamboat down the Ohio River, then up the Mississippi River to St. Louis where they bought a covered wagon and a team of oxen and headed west, I think for Kansas. Being 13 in number, 9 boys, 2 girls, and the parents, they couldn’t all ride. Grandpa and Uncle Ben, being 4 and six years old, rode with their mother while everyone else walked. It was probably December when they arrived in Miller County. Since winter was upon them, they obtained some kind of shelter and stayed and never went on to Kansas. This first winter was spent near the present location of the Miller County Nursing Home. Uncle Andrew later went on to Kansas and was there for awhile with Billy being born there. I think his stay in Kansas was about two years.

Neighbors in my boyhood were more than the people who lived in the area. They were people whom you visited often, and whom you exchanged work with at harvest time, butchering time, or anytime when help was needed. I can so well remember hog killing time, most of the time in December when it was cold enough to keep the meat from spoiling. Dad would get up before dawn and build a big wood fire. In this fire he would have some big rocks. After they had been heated to about red hot, he would put the rocks in a barrel of water to make it scalding hot. About daylight 2 or 3 neighbors arrived and a big hog was shot and immediately stuck in the throat with a knife to bleed him. Then about 3 men dipped the hog in the barrel which was tilted at a 45 degree angle, first the head, then the tail, not long enough to cook the flesh but long enough to loosen the hair and scruff. The men knew how long to dip it. Next, they laid it on board a platform and 2 men started scraping. This took some time as there were parts like the head which were hard to clean. While this was being done, another hog was done in and by that time the first one was ready to be hung by a gambrel stick pushed through the heel tendons to some firmly set posts. His belly was then split from tail to throat and the gutting started. After this he was hung head down. This procedure went on until, in our case, perhaps 5 hogs, 200 pounds each or more were slaughtered. Then they were cut up, 2 shoulders, 2 sides, 2 hams, the head, ribs and backbone. The meat was carried into the smokehouse, where the dogs couldn’t get it, to cool out and firm up overnight so it could be trimmed the next day. The guts had to be trimmed too as there was much valuable fat on them to be rendered into lard. Then late in the evening each neighbor who had helped, would take a ham, side, or shoulder or whatever portion he wanted, to be repaid when he butchered. Of course, Dad returned the work when they butchered. The meat next had to be salted heavily before curing and left to take salt for a couple of weeks. The salt would draw out much of the water, and this would have to be drained off several times. In 2 or 3 weeks when the water was finally drained out, the meat was hung from the ceiling joists by wires through each piece. A fire was then made from hickory wood on the dirt floor with the door closed to keep the smoke in the room. This smoking continued for about 4 days. The meat was then ready to keep all summer.

Note: Below this narrative by Arthur I have placed a pictorial story of hog butchering sent me by Pat (Wallace) Hill of Eldon.

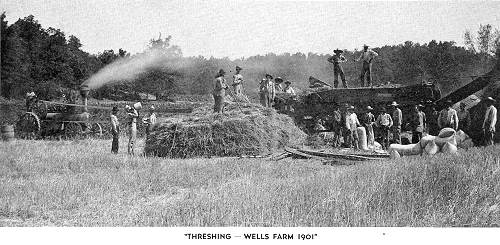

Another community activity was the annual wheat threshing. Unlike today, nearly all farmers raised wheat which was usually small acreages, many no more than 10 acres. Our neighbor, Charley Bill Abbott operated a threshing machine for many years (photo 23 of threshing machine on Wells Farm).

23 Threshing at Wells Farm

Click image for larger view

He threshed the wheat for 7 or 8 cents per bushel. Those machines were huge, cumbersome things, and were pulled from place to place by huge steam engines. Threshing time, except for the hard work, was almost a picnic. If my memory is right it took 12 to 15 men to carry out all phases of the operation. Two or three small crops could be threshed in one day. Moving the machine from one farm to the next was a very slow process, with the narrow dirt roads of the era and the huge powerful, but slow moving steam engine. All the help were farmers who had wheat to be threshed so work was swapped. No wages were involved. It was always known the day before where the crew would be at meal times, so it was also a day of work for the women. With the hard work involved, appetites were prodigious, so it required many women to do all the work. The women went all out to set a good table as there was prestige involved. Threshing time was usually in July so everyone had plenty of fresh vegetables and spring chickens as they were called then, would be of good size. Besides this everyone had a smokehouse full of cured pork. There would be different kinds of pies and cakes. It took a lot of food to fill up forty or fifty people including the women and children.

Thanks Arthur.

As I indicated above, Pat Wallace Hill of Eldon provided me some photos and narrative of Hog Butchering Day on her father, Jack Wallace’s farm north of Eldon.

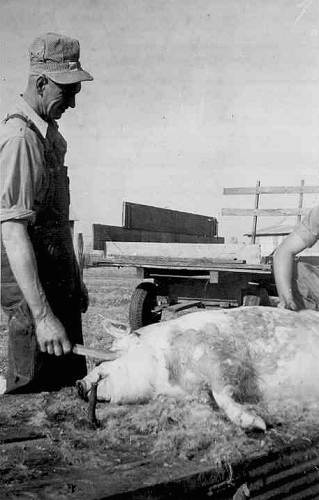

1. Bill Reynolds 1947 scraping hog at butchering time on the Jack and Ruby Wallace farm, north of Eldon (photo 24):

24 Hog Butcher Day

2. Bill Reynolds and Jack Wallace scraping hog. At right is hot water barrel. The hog was dipped whole body to make the bristly hair scrape off more easily (photo 25):

25 Hog Butcher Day

3. Bill Reynolds, daughter Shirley, and his wife Nellie (Karr) Reynolds cutting up bits of fat to cook down in big black iron kettle for lard (photo 26):

26 Hog Butcher Day

4. Jack Wallace stirring the black iron kettle, cooking the fat bits and pieces down to liquid lard. Then we poured it into a five gallon container with a tight fitting lid to be used in cooking as we would with Crisco today (photo 27):

27 Hog Butcher Day

5. Jack Wallace once again stirring the big kettle of fat pieces for lard. In back ground is the smoke house where the hams were hung after butchering. The smaller structure was a cover for the underground cellar. Also in the background are the white legged hens that which laid eggs to be crated and sent to Shaw’s Poultry in Olean (photo 28):

28 Hog Butcher Day

6. A very cold day! On butchering day the women always served liver and loin for dinner. In the photo are Ruby Wallace and Nellie Reynolds (photo 29):

29 Hog Butcher Day

Thanks Pat.

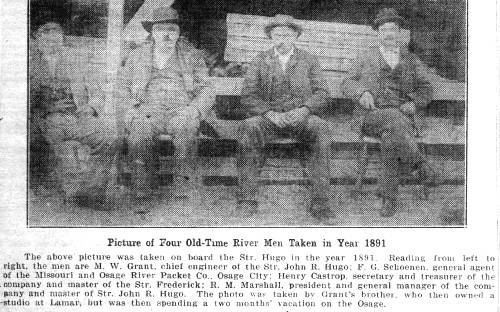

Captain Henry Castrop (photo 30) early in his life was a river boat captain and friend and business partner of Robert M. Marshall (photo 31) of Tuscumbia.

30 Henry Castrop

31 Bob Marshall

I have written extensively about Robert Marshall and his steamboat business on this page before in the Progress Notes of March 3, 2008.

Captain Castrop, being a number of years younger, was a devoted protégée of Captain Marshall. He was a quick and able student with a very good memory as well as having an affinity for writing and recording his memories of the years he worked on the rivers, especially the Osage River. He joined Captain Marshall in his steamboat business while yet a young man working as a steamboat captain of the Frederick for fifteen or more years. Here is an old photo copied from the Autogram of Captains Castrop and Marshall and their business associates (photo 32).

32 Captain Henry Castrop and other Captains

Click image for larger view

Quite a few of Captain Castrop’s articles were about his experiences as a river boat captain on the Osage, many of which were published in the Tuscumbia Autogram in the early 1930’s. I thought I would copy here over a number of weeks some of those articles as they make for not only historical but interesting reading as well. To begin I will copy a biography of Captain Henry Castrop which was sent me by his granddaughter, Celine Kingsman, who also sent me a couple of photographs of Captain Castrop, one of which I included above. The biography copied below is taken from a Westphalia newspaper still in publication named the “Unterrified Democrat.”

Henry Castrop: River Pilot, Publisher

Joe Welschmeyer

Unterrified Democrat Staff Writer

March 29, 1989

In an age when adolescence was a term never used in Westphalia, a young Henry Castrop learned fast what “growing up” meant. The location of the Osage and Missouri rivers near his hometown gave the youth a view of flatboat traffic on the inland waterways of his state and the post Civil War westward migration of easterners.

To the final years of his life, Henry Castrop, who lived from 1863 to 1937, kept close to the Missouri River. This is the story of a man who would have the eye and muscle of a river pilot as well as the mind and spirit of Osage County’s only publisher of a German-language newspaper. The Osage County Volksblatt was published at Westphalia from 1896 to 1917, when anti German sentiment brought about its demise.

Henry Castrop was born at Westphalia on January 28, 1863, the son of Conrad and Bernadine Koester Castrop. His birth took place in a village caught in the midst of Civil War political struggles. Living conditions were steadily improving by 1878, when the youth began working on flatboats on the Osage River. The boats carried supplies on short hauls from the rail point at Osage City and dropped off the freight at landings located along the Osage River as far as Tuscumbia, the seat of Miller County.

In the 1880’s, when steamboats replaced the area’s outdated flatboats, Henry Castrop went into a company venture with Messrs. Marshall and Hauenstein (photo 33) of Tuscumbia.

33 William H. Hauenstein

The boating enterprise built a steamer, “The Frederick,” (photo 34) and Castrop became its pilot. Thus he earned a lifelong title, Captain Castrop.

34 Steamer Frederick at Tuscumbia Landing

The steamboat Frederick plied the waters of the Osage and Missouri rivers for many years. The cargo consisted of anything the inland farmers and merchants wished to ship to a rail point or to Jefferson City. The trips inland were to deliver packets or manufactured goods. Passengers were among the deliveries made. From a point known as Castrop’s Landing, a surrey ride would transport them the remaining four miles to Westphalia.

In the summer, the parish picnics in the area meant free passage across the Osage River, as well as to the rail station at Osage City. Picnic goers could then return to eastern and western stops on the Missouri Pacific railroad line.

Although the date has not been determined, the Frederick finally sank in the ice after having wrecked near the site of the present Jefferson City Bridge. Other boats built and used by the river company included the Hugo and the Osage.

The second business venture of Henry Castrop was publishing a German language newspaper at Westphalia. Already in 1894, a John H. Boss from Hermann established a newspaper at Westphalia entitled The Westpalia Leader. The paper presumably was an English publication, though no copies are known to exist from its two years in business.

In 1896, Captain Castrop acquired the newspaper equipment and began publishing a four page German language Osage County Volksblatt. The circulation served primarily the Westphalia community and to some extent Koeltztown, which then included some five present day parishes. The reason for the limited circulation was the Jefferson City Volksfreund and the German newspaper at Hermann, and after 1903, the Home Adviser at Brinktown and Vienna also carried a German edition.

None of these areas subscribed to Linn’s Unterrified Democrat in the early 1900’s.The U.D. at that time was strictly a courthouse and Linn community newspaper.

The Volksblatt was not a political organ and, although it carried political advertisements, it did not side with any party. Noticeably absent from the front page were any articles speaking of new developments or community improvements. The headlines were church items, religious festivals, weddings, anniversaries, and some farm sales or the purchase of a new bull.

Market news from the local milling company, social news and obituaries were followed by correspondence from other German speaking communities. Occasionally there was correspondence from elsewhere in Missouri, as well as Oklahoma and California … areas where Westphalians had emigrated in the 1870’s and 1880’s.

Some headlines were: “Der Hochwurdigfte Erzbischof in Westphalia”; “Die einzige deutdeutsche Zeitung im County”’ “Zu Verkaufen”; “Neu Isenbahn bei Freeburg”; “Grosses Volksfest August 1902”; “Katholikversamlung in Freeburg”; “Zur Geshihte Company D”; “Lazt die Kinder deutsch Lernen.”

Social developments brought continued change and less emphasis on the “foreign” atmosphere which prevailed in Westphalia. Perhaps this began even before the Jesuit pastors were recalled in 1884. By 1914, World War I had begun in Europe. In Osage County the average German American was clearly interested in the welfare of relatives and former neighbors in the “fatherland” of Prussian Germany.

From 1917 through 1919 there existed in Missouri various local units of an organization known as the Missouri Council of Defense. In Osage County the organization had a chapter at Linn.

The Osage County Republican contained one of the group’s “pronouncements” advising people of the county to neither use the German language in church services, school instruction, public conversation or especially on party line telephone conversations.

The German Council of Defense reported in 1917 that, since the beginning of the war, German language newspapers had decreased in number in Missouri from 15 to 10 and that several of them were printing half English or were preparing to cease publication or would convert to exclusive use of the English language.

On April 6, 1917, telegraph lines brought the news to Osage County rail stations that Congress had declared war on the central powers, Germany and Austria Hungary.

Since January of 1917, German U boat submarines had been trying to starve out England by destroying any ships carrying cargo to England. This unrestricted sub warfare lead to the declaration of war. In May of 1917 the first draftees of the selective service were called in Missouri.

By the end of the war some 92,843 men were drafted from the state. Among the first draftees were men selected from the German speaking communities of Osage County.

In Jefferson City, Governor Frederick D. Gardner organized the Council of Defense and placed it under the leadership of Dean F. B. Mumford of the College of Agriculture at the University of Missouri.

Henry Castrop was in a tense situation with his Volksblatt located so close to the state capital. Already he must have heard of the destruction of the presses of a German newspaper in Cape Girardeau carried out by a group of zealots in southeastern Missouri.

“Zurn Abscheid;” the closure, was the headline of the last issue of the Osage County Volksblatt. The last issue of the Westphalia publication was printed on July 19, 1917.

After 21 years of publishing the newspaper, Castrop saw it in his best interest to cease publication.

It is difficult in 1989 to see more deeply into Castrop’s reasons for closing. However, in his own published account his words gave no reference to the strong anti German sentiments then in force.

Castrop stated three reasons for ceasing publication:

1. The use of the German language had declined among the younger generations of German descent at Westphalia.

2. There were unpaid subscriptions due him in the amount of $1000. He promised to refund those who had paid the advance price at $1 per year’s subscription.

3. The main reason for closing was the tremendously high cost of newspaper print and for all materials used.

The building which housed the print shop was located on Westphalia’s main street. It had living quarters above the shop. Later it would be used for the Farmers and Merchants Bank, long since razed (the location was between the present homes of Syl Redel and Al Schwartz).

The earlier Castrops had come to Westphalia from Mettinghausen, Westfalen, Germany. After Henry Castrop’s youthful days on river flatboats he married Ann Radmacher in 1884. One child was born of the marriage; however the child and later the mother died. Castrop then remarried on May 2, 1899 to Caroline Birkle at Westphalia.

In 1919, Henry Castrop moved his young family from Westphalia to a 150 acre farm in the Missouri River bottoms of West Glasgow in Saline County. He joined with other German Americans who relocated there…among them his brother, Joseph Castrop, who lived from 1865 to 1841, as well as farmers from the Dutzow and Washington areas.

Eight children were born to his second marriage, including Veronica (Fronie), Philomine Meyer, Clarence, Angeline, Herbert, Thomas, Raymond and an infant. A daughter Cecilia from the first marriage died at age 14 in Westphalia in 1914. Clarence lived from 1909 to 1938 and Thomas died in 1972.

The Castrop family farmed in the Missouri River valley and were members of the All Saints Church, a rural parish in the west bottoms. In 1925, Caroline Castrop died. Veronica, the oldest daughter, then raised her siblings with her father’s help. In time the family members would live out their lives in Kansas City and the San Fernando Valley of southern California.

On February 24, 1937, Captain Henry Castrop died at his home about six miles west of Glasgow. His remains were buried in the rural All Saints Cemetery atop the hills, above the floodplain. His gravesite was never marked with a monument but it is beside one he placed there for his wife, Caroline in 1925.

It is fitting that a man who first made his mark on the world of river boating should be buried overlooking the Missouri River. It is ironic, however, that the man who chronicled the weekly life of Westphalia from 1896 until 1917 has no words inscribed in stone over his place of rest.

I previously copied one of Captain Castrop’s articles in which he discussed the “tie rafters” who skillfully worked the tie floats down the Osage River. You can read it in the Progress Notes of July 28, 2008.

The article I copy today from an old Autogram was written by Captain Castrop about the huge amount of goods shipped up and down the Osage River and in particular about the men, called “roustabouts,” who did the lifting and moving of freight. One singular feature of this essay by Captain Castrop will stand out immediately to the modern reader, but which, in those days would not have raised an eyebrow. For many years after the Civil War, the Black Americans who supposedly had been liberated, in truth, continued to live lives of near slavery and to be treated with disrespect. The reader will find the word “nigger” repeated often in this essay by Captain Castrop, a word which then and for more than a century after the Civil War was used frequently and by habit without any hint of approbation for its use. Times have changed and now we are witness to the historical event of having elected our first Black American as President. For historical accuracy I have copied the article exactly as it was printed originally:

Vast Amount of Freight

Captain Henry Castrop

Tuscumbia Autogram (date unknown, estimated mid 1930’s)

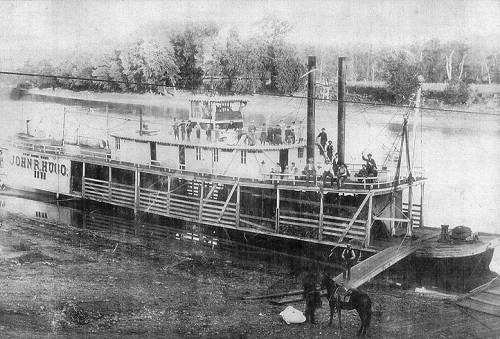

For a number of years, Captain R.M. Marshall was employed by the U.S. War Department in towing government barges on the Missouri river with the Steamer Hugo (photo 35), which he owned.

35 John R. Hugo owned by Bob Marshall

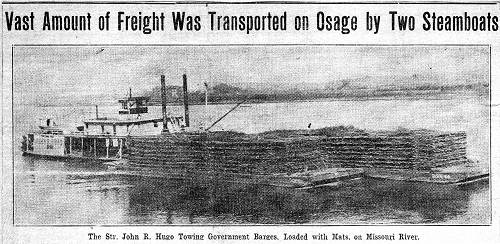

The Hugo had a light draft and the War Department, for that reason, employed Captain Marshall in the river revetment work on the Missouri. The government mat barges were 100 feet long, and the Hugo usually had 2, 3, or 4 barges in a tow (photo 35a).

35a Hugo Loading Mats

Click image for larger view

The mats were willow limbs and were cut and loaded on barges by men and teams, then transported to places where the river work was being done. The mats were delivered to mat boats, where mat weavers were employed in weaving the mats just as though they were making rugs. The mat boats were 64 feet long and had sloping platforms which extended to the water’s edge. When the mats were woven the boats were moved from under them and they were lowered into the river and held in place by rock or by piling driven through the mats. These mats kept the banks from washing and the piling dikes assisted in causing the river to deposit silt and hold the banks from washing. Many interesting stories could be told of this work.

That the reader may form an idea of the vast amount of freight carried by the Frederick and Hugo out of the Osage River, it may be here mentioned that the number of wheat sacks delivered to the Missouri Pacific at Osage during one year was 115,000, for the John R. Hugo, while the Frederick’s books showed 99,000 for the same year. Live stock handled was on the average of over 200 carloads for the year. Poultry and eggs (hen fruit as our “niggers” would call them), was quite a large item on the freight lists.

The handling of this vast volume of freight required quite a number of roustabouts. Each boat would have from 12 to 20 on the trip and more labor was hired when unloading or loading in port. Negro roustabouts were preferable to a white crew. They would trod with their loads on their shoulder, be it sacks, ties or lumber, be it pushing their wheelbarrows loaded with tiff, all day long, not minding the burning hot sun in the least which most white men were not capable of doing. This, we experienced when one time we, for some reason, could not get a crew of Negroes to make the trip, we were compelled to hire a white crew at Tuscumbia. The boys did well. By the time we reached Shipley Shoals we had over 4700 sacks on board the Hugo and barge. Then came the trial. We stuck on the shoals and as the river was falling fast, we were kept there for seven days. Every sack with the exception of four hundred that the barge Jumbo floated over with, had to be transferred over onto the Frederick and her barge and taken by small numbers at a time below the shallow water where they were put on the bank. After the Hugo was so relieved of her cargo, she was then pulled over the ten inches of water she was on, by her steam capstan into deep water. When the sack pile on the bank was sighted …and 5000 sacks all in one pile, all to be carried aboard again, means something…every man of this crew asked for his pay and walked back to his fifty mile distant home, Tuscumbia. The rule that captain, pilot, engineer, foreman, watchman, cook, would in an emergency take the place of the roustabouts, was not followed this time. The Hugo steamed to Osage light, coming back with the old reliable crew of “niggers’ who were not long in toting the sacks back onto the boat. Such trips, being detained for a week on a bar, were not enjoyed by either officers or crew, nor were they profitable to the owner.

While the shippers of this cargo of wheat, which during this time had advanced 7 cents a bushel in the market, came out ahead, the boat company lacked but little coming out in the hole.

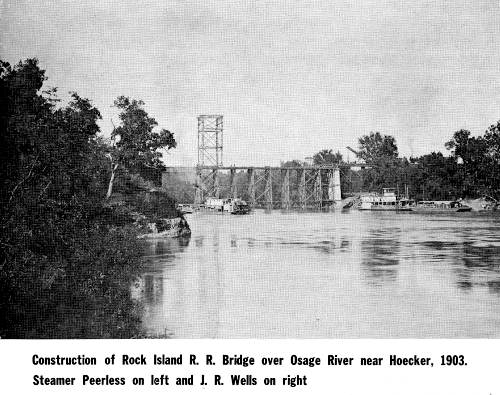

Leaving the boat in a pinch by deserting her, was sometimes, too, practiced by the Negro roustabouts. But never would this occur anywhere in Miller County. From this county the colored race was banned. Any Negro not heeding this edict was shot down or hanged. This being a proven fact and known to our Negroes, they were loathe to go on shore when the boat was landed. It was one night though, in years later, when the entire Negro crew of the steamer, Osage, were made to take the bank at Hoecker’s where they refused to unload a dozen 2 X 8 boards for the construction gang then building the railroad bridge (photo 36).

36 Hoecker Bridge Construction

This gang would always unload the freight we had on board for them with their derrick, but not having steam on their boiler that night, our “niggers” then enjoying an interesting crap game, refused my demand to unload this freight. Angered by their stubbornness, I handed them their pay and told them to get of the boat. “You will not put ashore here in Miller County, Captain,” they retorted. “Miller County or no matter where.” I replied, “You take to the bank,”

“If you cannot get rid of these ‘niggers’, Captain,” came from the bank, the voice of one of the men, “tap your bell and we will assist you.”

These words had their effect. They all gathered up their duds and went with the exception of one who was sick or played sick. The few boards were taken off by the boat’s officers and on she went to her destination further up the river. Coming into Osage the next day with over 2000 sacks aboard, which had been loaded by the boat’s crew, assisted by the no longer sick nigger, we found our Negro roustabouts waiting at the bank ready to unload the boat. They had walked from the bridge site at Hoecker to Padgett Hollow, the next camp below, where they had their checks cashed, with the saloonkeeper there for whiskey, for the remainder they had hired conveyance to Jefferson City.

Roustabouts then and long before those days, were paid one dollar a day and their board, they were allowed to pick their bunks to sleep in wherever they would find them convenient, either in the engine room, on the lower deck of the boat, or on a sack or freight pile. A roustabout’s day consisted of twenty four hours which day was entirely or partly devoted to work, sleep or play. Work was demanded of him while the boat loaded or unloaded her cargo at landings, no matter whether this took one hour or twenty four hours. Rest or play was his only while the boat was plowing the water. I do not know whether the roustabout of today, like all other labor, has his eight hour shift at good pay, or has his profession more in common with another, that of the soil tiller…the serving of humanity for long hours at small pay.

A couple of weeks ago Patsy Adcock Wickham, who has been a regular contributor to our museum of various historical materials, brought over an old corn cob pipe her father, Garland Adcock, had enjoyed for many years. Sometime before she had already donated the wooden folding chair Garland sat on every day when he was resting for a few minutes taking time off from his chores running the store he and his wife, Edna, owned on the south side of the Osage River just across the bridge from Tuscumbia. This particular corn cob pipe is unusual in that it has a very long stem, which among other things, allows the smoke inhaled to be cooled a bit before reaching the mouth. Patsy said this pipe was very old and she doesn’t know how long her father had used it. Here is a photo of Patsy demonstrating her father’s old corn cob pipe (photo 37).

37 Patsy Adcock Wickham with Father Garland Adcock's Corn Cob Pipe

Corn cob pipes were homemade to begin with but about one hundred fifty years ago some of them began to be made and sold commercially in Washington, Missouri by a company later called the “Missouri Meerschaum Company” which still exists. In 1939 a competing company, Buescher Industries, also began making the pipes. The pipes were so popular for a time that many people of note used them including General Douglas MacArthur.

In our area of Missouri I remember that my father and his two brothers sold many of them through their own business (making of cedar wood craft items) marketed here in the Ozarks as well as nationally through their catalogue mailings.

Next time you visit the museum you can find the corn cob pipe given us by Patsy located in the bedroom of the “dog trot” house next to some other old pipes of long ago we have on display. Listed below is a website which contain some information about the corn cob pipes of Missouri:

New York Times article: "Corncob Capital of the World"

That's all for this week.

|